The Weeping Time

A forgotten history of the largest slave auction ever on American soil

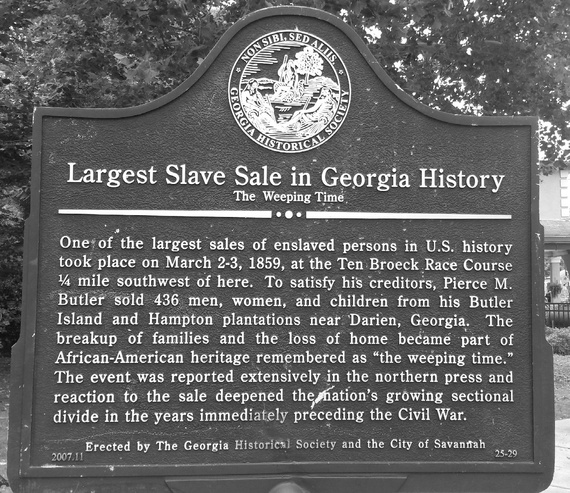

The marker reads:

And that's it for the city's commemoration of the event known as the Weeping Time. Contrast that with the towering monument to the Confederate dead that has stood for over a century smack in the center of one of the city's largest public parks.

The event wasn't just notable because of the size of the auction. In 1859 the country was on the verge of a national bloodbath, and the historic threads that weave through the story of the Weeping Time are so far-reaching and remarkable, it's perplexing that more hasn't been written or remembered about this time.

* * *

Pierce Mease Butler, the owner of the slaves who were sold, inherited his wealth from his grandfather, Major Pierce Butler, one of the largest slaveholders in the country in his time. One of the signatories of the U.S. Constitution, Major Butler was the author of the Fugitive Slave Clause and was instrumental in getting it included under Article Four of the Constitution.When Major Butler died, most of his estate and holdings were passed on to Pierce M. Butler and his brother John, including two sprawling island plantations on the coast of south Georgia, one that produced rice and one cotton, and more than 900 slaves who worked the plantations.

Pierce M. Butler was a profligate steward of his inheritance, regularly engaging in risky speculations and accruing a considerable amount of gambling debt over the years due to his compulsive card playing. It was these two factors that necessitated the appointment of a group of trustees who, in 1856, seized control of his financial assets in an effort to return him to solvency. Over the next few years the trustees proceeded to sell off various Butler properties.

By 1859 the trustees were still unable to extricate Pierce Butler from his debts, and it was decided that the “movable property” on the Georgia plantations would be split between Pierce and his brother John, and the half of the slaves that were allotted to Pierce would be sold at auction to relieve his remaining financial obligations. A small fraction of those obligations were the quarterly payments Pierce Butler was required to pay to his then-estranged ex-wife Frances Anne Kemble as part of their divorce agreement 10 years prior.

Fanny Kemble was a revered Shakespearean actress from London on tour when she met Butler in Philadelphia. Kemble was, by all accounts, a strong-willed and independently minded woman of her own making, tendencies Butler aimed to tame. Nevertheless, they were married two years after Butler's unremitting courtship and Kemble reestablished herself in America.

Once Kemble found out about Butler's Georgia plantations, she begged him to take her down to witness first hand what she'd previously only heard and read about in her native England. Despite his better judgement, Butler brought Kemble with him in late 1838 to visit the plantations and what Kemble found was every bit as callous and horrible as she'd imagined. Kemble cataloged her stay in her diaries, which were eventually published some years later as Journal of a Residence on a Georgia Plantation (1838-1839) and to this day it's considered one of the most detailed eyewitness accounts of slavery during that period.

(Kemble's journals weren't published until 1863—in the middle of America's Civil War—due to custody issues with Butler over their two daughters. Butler had “forbade” the publication of the journals during their marriage, but once their daughters were “of age” Kemble felt free to let her account of that time be known to the world. Her journals ended up playing a significant role in the anti-slavery debate raging at the time.)

Kemble was long out of the picture by the time the Butler slave auction took place (they were divorced in 1849). But the most virulent phase of great slavery debate was only just getting under way. Just a few months before the Butler auction, the now infamous slave ship the Wanderer had landed at Jekyll Island off the coast of Georgia with more than 400 illegal slaves brought directly from the Congo. This was one of the last documented slave ships to arrive in North American and it created a roiling controversy. The transport of slaves from Africa had long been outlawed, but owners of the Wanderer, with the help of the pro-slavery “fire-eater” Charles Lamar, disguised their ship as a luxury cruise liner and brought back a hull-full of “human chattel,” thumbing his nose at federal law. Records indicate that nearly 80 slaves perished on the voyage.

* * *

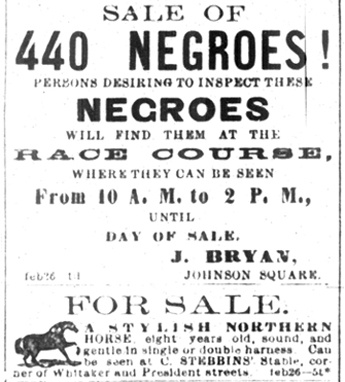

The notorious slave trader Joseph Bryan was enlisted to conduct the Butler slave auction and it was originally scheduled to take place in Savannah's Johnson Square, directly in the city's center, where Bryan's slave holding pens and brokerage was. But it was soon determined there wouldn't be enough room to accommodate the buyers they expected, so the location was moved to the Ten Broeck Race Course two-and-a-quarter miles west of downtown.For weeks before the auction, Bryan took out ads in papers across the south advertising the sale. It became the talk of the town and speculators from as far as Louisiana and Virginia came to Savannah to ply their bids. One of the ads that ran in the weeks before the auction in the Savannah Daily Morning News read:

Thomson posed as a potential buyer to get close to the action and judging by the reaction in the South once his piece was published, it was a wise decision for him to travel incognito. After “Great Auction Sale of Slaves at Savannah, Georgia” came out in the Tribune, it was republished in Philadelphia and London and caused an international stir. Threats on his life from public officials in the South were issued. They claimed the piece was an anti-slavery hit-job by northern abolitionists. In fact that's exactly what it was.

2007 aerial view of the site (Kwesi DeGraft-Hanson)

When Thomson recounts the auction, he holds nothing back. By its very nature, the sale of human beings is a disgraceful affair and he describes the slave speculators as a motley lot, poking and prodding the “chattel,” pinching their muscles and checking the insides of their mouths like livestock, all while joking and making lurid comments at some of the female slaves. He goes into detail about a few of those who were sold, including a man named Jeffrey who attempts to entreat his buyer to purchase a woman named Dorcas, his fiancee, only to eventually be rebuffed when the buyer finds out he would have to purchase her whole family to acquire her.

Thomson spends some 20-odd pages relating the events of the auction and its aftermath, including Pierce Butler showing up and extending a gloved hand to a few of his favorite slaves, and after the auction, giving each of those sold $1 in freshly minted coins, as if that were consolation to the families who had spent generations on his plantations and were ripped apart on those two days. It's a shattering portrait of the realities of the slave trade, and deserves far more exposure than it's had since it was first published, as do Kemble's journals.

* * *

The city of Savannah should be commended for recognizing this monumental event with a historic marker, but one small plaque in a remote West Savannah park doesn't nearly do justice to the memory of the people who were bought and sold so many years ago. Our country—particularly the south—is full of these hidden histories and if we as citizens don't labor to remember these admittedly ugly episodes of our past, we're doing not just ourselves a disservice, but we're desecrating the memory of the enslaved people who helped build this country.The Ten Broeck Race Course has since been obliterated and there's now a lumber company on most of its former site. An elementary school sits on one corner of the former racetrack, but there's not a single trace left of the old course and it's probably safe to assume that very few, if any, of the children who attend classes there even know what happened on those grounds a century and a half ago

No comments:

Post a Comment