AMERICAN INDIANS

A story told for thousands of years.

For European explorers, North America was a new world. For American Indians, it was an ancient one, already filled with the stories of their lives. Beginning in the 16th century, both versions of the world would change forever.

The stories of Texas didn't begin with the arrival of Spanish explorers in the 1500s. Hundreds of different groups of native peoples with a variety of languages, customs, and beliefs lived on the land for at least 11,000 years before the arrival of Europeans. For the American Indians, Texas had long been their world. The land, the life, and even the other native peoples they encountered were already familiar. It was the explorers who were new.

Starting the Stories

By the time those explorers got to the new world, American Indians had created long arcs of histories and cultures in Texas. From the Gulf Coast to the Panhandle, from the piney eastern woods to the barren southwestern plains, native peoples had established themselves as traders, hunters, food-collectors, artisans, and healers. They had crafted ways of life based on what the land required. They had forged and broken alliances, competed for resources, and traded with each other for centuries. American Indian tribes such as the Karankawa, Caddo, Apache, Comanche, Wichita, Coahuiltecan, Neches, Tonkawa, and many others had already written extensive chapters in the story of Texas by the 16th century. One of them gave the story a title, and another, a conflict.

The Caddo

In the Caddo language, taysha means "friend" or "ally." The Spanish spelled it tejas. We call it Texas.

By the time European explorers arrived, some Caddo communities had settled along the Red River and in East Texas from their homelands in Louisiana, Arkansas, and Oklahoma. There were as many as 25 separate Caddo groups linked by language and customs, including the Hasinai alliance, who settled mostly in East Texas.

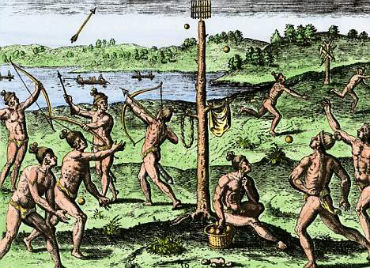

When the Spanish and the later French explorers encountered the Caddo, they experienced firsthand that long arc of already-established American Indian history and culture. Caddo groups lived in settled communities with complex social and political structures, advanced agricultural practices, and organized spiritual ceremonies and rituals. By the 16th century, the Caddo had developed a reputation for being fierce warriors, extraordinary artisans, and very skilled traders. It was this last quality that most intrigued the Europeans. It would also come to decimate the Caddo.

A Changed World

By the late 17th century, Spanish and French explorers were engaged in a frenzied race to plant flags in Texas. Land in North American meant new resources, new power, and new wealth for the mother country.

The Euopeans were also engaged in a frenzied race to claim the Caddo as deal brokers for their flag-planting goals. As they saw it, the Caddo offered them two distinct advantages: 1) their Red River and East Texas homelands were located in prime trading areas, and 2) Caddo leaders were recognized by other American Indian tribes and the increasing number of transplanted Europeans as being savvy and skilled traders. The Caddo did indeed prove to be accomplished facilitators, and during the 17th and 18th centuries, an increasing number of European goods and settlers moved into Texas, along with cholera and smallpox.

It has been estimated that perhaps 95% of the Caddo population was decimated in major epidemics between 1691 and 1816. Although the Hasinai continued to live in East Texas through the 1830s, other Caddo groups moved on to present-day Oklahoma and Kansas to escape disease and attack from other American Indians. Today, the Caddo live primarily in Caddo County, Oklahoma.

The Apaches

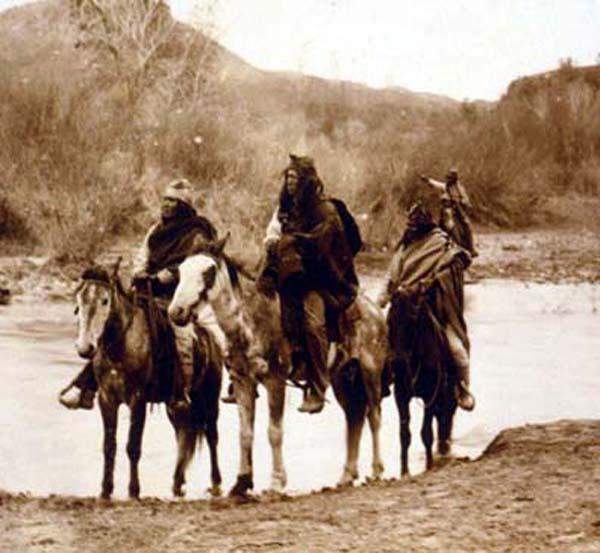

Dominating almost all of West Texas were the Lipan and Mescalaro Apaches. The nameApache may have come from the Zuni word apachu, meaning enemy, or from the Ute name for Apaches, Awa'tehe. Apaches were among the first American Indians to ride horses. This allowed them to live a nomadic life following the buffalo herds from place to place.

Life As An Apache

For both Lipan and Mescalero Apaches, the basis of their social structure was the extended family. While tribal leaders were always male, the lifeways of the tribe were often shaped by the females and their families. For example, when an Apache male married, he went to live with his bride's family. He hunted and worked with her relatives. If his wife died, it was tradition that the Apache husband would remain with his in-laws, who would often provide him with a new bride.

The Apache of the Panhandle Plains traded extensively across the Southwest, exchanging stone tools of alibates flint and hides and meat from bison and deer for corn, pottery, turquoise, Pacific coast shells, and obsidian. The Apache dealt extensively with Pecos Pueblo, the great trading center in present-day New Mexico.

"Only to the white man was nature a wilderness and only to him was the land 'infested' with 'wild' animals and 'savage' people. To us it was tame, Earth was bountiful and we were surrounded with the blessings of the Great Mystery."

- Black Elk, Oglala Lakota Sioux

Buffalo hunting was the Apaches' main occupation as the animals provided most of their needs for food, clothing, and tipi covers. Until horses came to the Plains in the late 1600s, the Apache hunted and traveled on foot, using dogs as pack animals. The Apache gradually extended their influence over a large area, moving southward into Central Texas. Known as Lipan Apache by the late 1600s, they were pushed farther south by the formidable Comanche and Kiowa.

Texas's American Indians had been making and breaking alliances with each other for centuries by the time Spanish settlers arrived. Colonists complicated the mix, shifting alliances with different American Indian groups as circumstances changed.

Missionaries Arrive, Apaches Depart

In 1757, Spanish friars established Mission Santa Cruz de San Sabá north of San Antonio for the Lipan Apache. The missionaries hoped to convert the Lipans; the Apache hoped the friars would protect them from the Comanche and other enemies. Neither the missionaries nor the Apaches anticipated the deep hostility of Apache enemies who completely destroyed the mission in 1758 to break the Lipan-Spanish alliance.

Few American Indians converted to the Catholic faith. Most were generally indifferent to the missionaires, and differences in languages, beliefs, and everyday customs made many interactions between the two groups almost impossible. However, they were linked by their interdependence. Missionaries needed the Lipans to build and maintain the mission structures and to farm the land. Lipan Apaches found that life in the missions provided them a safe haven from powerful enemies.

However, relations between the two groups themselves weren't always smooth. Some Lipans maintained their cultural traditions while living in the missions, causing much frustration for the friars. The Lipan were equally unhappy by the friars's exhaustive labor demands and poor food supply. By 1767, the Apaches had moved on from Spanish mission life and back into the landscapes of Texas and Mexico.

No comments:

Post a Comment