October 23-25, 1884: The first "World Series"

This chapter is not about a single game. Instead, it is about three games, the first post-season interleague series intended to create a baseball “Championship of America” or a “World’s Championship.” Although nearly all baseball fans rattle off 1903 as the first World Series, this 19th-century match-up is recognized among baseball historians as the real first “World Series.” There was no model for post-season interleague championship play before 1884. No such series had even been possible until 1883 when the National League, the American Association, and a minor league (the Northwestern League) reached a peace settlement that became known as the Tripartite Agreement or National Agreement.

There was no model for post-season interleague championship play before 1884. No such series had even been possible until 1883 when the National League, the American Association, and a minor league (the Northwestern League) reached a peace settlement that became known as the Tripartite Agreement or National Agreement.The 1884 season started with unprecedented excitement for fans (then called cranks) and great anxiety for team owners. The cranks had much to be excited about with more teams and players to follow after the addition of a new upstart league, the Union Association, and the expansion of the American Association. Meanwhile, owners fretted over players jumping their contracts to join the new league and over greater competition for attendance from it.

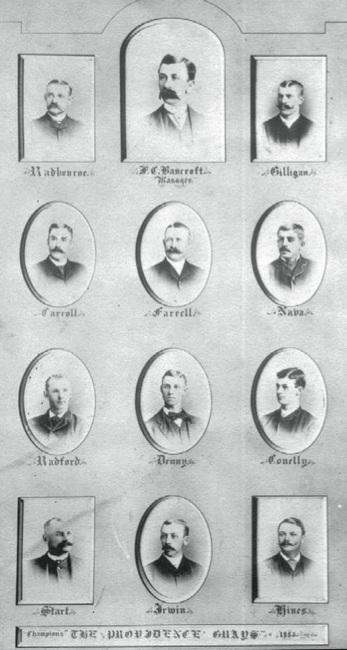

The established circuits moved through their schedules pretending the UA didn’t exist. In the NL, the Providence Grays were highly regarded. The Grays had won the pennant in 1879, finished second in ’80, ’81, and ’82, and third in ’83. In the AA, the Metropolitans of New York showed hope when they landed in second a few weeks into the season.

The Grays were managed by Frank Bancroft, in his first season with Providence and his fifth as a major-league manager. The Mets were led by Jim “Truthful Jeems” Mutrie, who had organized and managed the team as a Manhattan-based independent club in 1880 with financial backing from John B. Day, and placed the team in the AA in 1883. Mutrie continued as manager through this 1884 championship season.

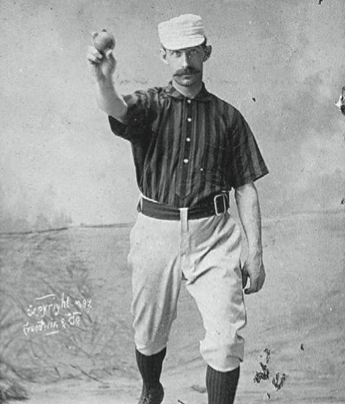

Both teams believed that “good pitching beats good hitting.” The Grays had Charlie Sweeney and Charles “Old Hoss” Radbourn, while the Mets relied on Tim Keefe and Jack Lynch. In July, while the Grays were battling for the NL lead, Radbourn was suspended for indifferent play.1 A week later, Sweeney, an incurable alcoholic, was released.2 Radbourn returned and was nearly untouchable, winning 35 of his next 40 games, giving him a record 59 wins, the all-time major-league season high. Keefe and Lynch finished with 37 wins each.

Although the Mets didn’t wrap up their pennant until the last week of the season, Mutrie began an early campaign to play Providence, the likely National League winners. Mutrie and Bancroft were old associates. Mutrie had played shortstop on Bancroft’s New Bedford team in 1878 and the two had managed or played contemporaneously from 1876 through ’79.

There were, however, issues to be worked out: number of games, rules, where to play, and finances. As challenges started in the form of wagers, with the winning team’s players taking all, the National League was not enthusiastic and was relieved when the managers worked out a split of the proceeds. Although Mutrie offered a five-game series of two games in each team’s city and a fifth game, if necessary, in a neutral location, Bancroft did not want to risk the travel expenses. Because Manhattan’s population was 1.2 million, Bancroft proposed a threegame series at the Polo Grounds in Manhattan, then located at 110th Street and Fifth Avenue.3

There were, however, issues to be worked out: number of games, rules, where to play, and finances. As challenges started in the form of wagers, with the winning team’s players taking all, the National League was not enthusiastic and was relieved when the managers worked out a split of the proceeds. Although Mutrie offered a five-game series of two games in each team’s city and a fifth game, if necessary, in a neutral location, Bancroft did not want to risk the travel expenses. Because Manhattan’s population was 1.2 million, Bancroft proposed a threegame series at the Polo Grounds in Manhattan, then located at 110th Street and Fifth Avenue.3It was decided that the American Association’s rules would be used. Bancroft had sought an exception permitting use of the NL pitching rule—which allowed the ball to be thrown overhand. That would have been an advantage to Radbourn. Instead the AA rule, which prohibited the pitcher from raising his arm above the belt, was used.4

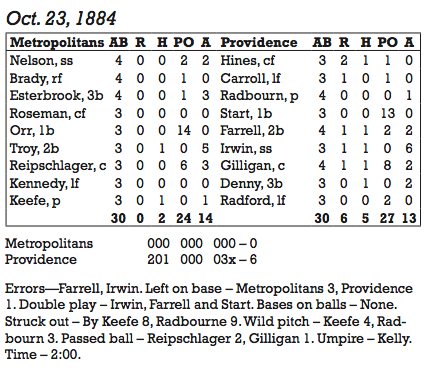

The games were scheduled to take place on Thursday through Saturday, October 23–25. Two victories would crown the champion. Radbourn was to pitch all three games, which was no surprise, given that he pitched nearly every game after Sweeney jumped the team. This was not good news for the Mets and their cranks. Nor was it good news that the injured Jack Lynch was unable to pitch, requiring that Keefe might have to pitch all the games.

Bad news or not, a championship series in the nation’s largest and wealthiest city had everyone convinced that these would be the greatest games ever played. On Wednesday the 22nd a huge throng began assembling in the afternoon for a torch-lit parade. It was 76 degrees. Just as the evening parade got underway, rain began and the temperature fell. The rain and wind increased, and the cranks dispersed.

The next day was horrible. The rain stopped, but the temperature never got above 51 and a whipping wind made it feel colder. Only 2,500 cranks turned out, one-tenth of the expected crowd. Keefe was decidedly off his game, and Radbourn surprised no one, winning 6–0.

That outcome put the onus on Keefe to attempt to prevent a Providence championship in Game Two (although all three games were scheduled to be played, regardless of the outcome of the first two). With temperatures in the 40s and because of the Mets’ poor play the day before, the turnout was only about 1,000. Keefe was sore from the previous day and although he made it closer, holding the Grays to three runs, Radbourn allowed the Mets only one, in a game shortened to seven innings by darkness. The Grays were now the “World’s Champions.”

Game Three was punishing. The game was nearly canceled as the Grays balked at playing a meaningless game before 500 freezing cranks. Much to their credit, they gave in to the Mets, who reminded them how often the New York National League team (also owned by Day) had to play before small crowds in Providence.5 The Mets’ Buck Becannon pitched only his second game of 1884, a 12–2 loss in a contest called after six innings because of the cold.

Providence was able to celebrate only briefly— the following season was its last as a major-league city. More importantly, post-season interleague championship play had been introduced at the major-league level. Although there would never be as short a series, the World Series tradition had begun. It would continue, with only a few lapsed seasons, right up until today.

This essay was originally published in "Inventing Baseball: The 100 Greatest Games of the 19th Century" (2013), edited by Bill Felber. Download the SABR e-book by clicking here.

No comments:

Post a Comment