Ivory Coast

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For other uses, see Ivory Coast (disambiguation).

| Republic of Côte d'Ivoire

République de Côte d'Ivoire (French)

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Motto: "Union – Discipline – Travail" (French) "Unity – Discipline – Work" | ||||||

| Anthem: L'Abidjanaise Song of Abidjan | ||||||

|

Location of Ivory Coast (dark blue)

| ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Capital | Yamoussoukro 6°51′N 5°18′W | |||||

| Largest city | Abidjan | |||||

| Official languages | French | |||||

| Vernacular languages | ||||||

| Ethnic groups(1998) |

| |||||

| Demonym |

| |||||

| Government | Semi-presidential republic | |||||

| - | President | Alassane Ouattara | ||||

| - | Prime Minister | Daniel Kablan Duncan | ||||

| Legislature | National Assembly | |||||

| Independence | ||||||

| - | from France | 7 August 1960 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| - | Total | 322,463 km2 (69th) 124,502 sq mi | ||||

| - | Water (%) | 1.4[1] | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| - | 2014 estimate | 23,919,000[2] (53rd) | ||||

| - | 2014 census | 22,671,331 | ||||

| - | Density | 63.9/km2 (139th) 165.6/sq mi | ||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2014 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $48 billion[3] | ||||

| - | Per capita | $1,938[3] | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2014 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $32 billion[4] | ||||

| - | Per capita | $1,302[4] | ||||

| Gini (2008) | 41.5[5] medium | |||||

| HDI (2013) | low · 171st | |||||

| Currency | West African CFA franc(XOF) | |||||

| Time zone | GMT (UTC+0) | |||||

| - | Summer (DST) | not observed (UTC+0) | ||||

| Drives on the | right | |||||

| Calling code | +225 | |||||

| ISO 3166 code | CI | |||||

| Internet TLD | .ci | |||||

| a. | Including approximately 130,000 Lebanese and 14,000 French people. | |||||

Ivory Coast ( i/ˌaɪvəri ˈkoʊst/) or Côte d'Ivoire (/ˌkoʊt dɨˈvwɑr/;[7] koht dee-vwahr; French: [kot divwaʁ] (

i/ˌaɪvəri ˈkoʊst/) or Côte d'Ivoire (/ˌkoʊt dɨˈvwɑr/;[7] koht dee-vwahr; French: [kot divwaʁ] ( listen)), officially the Republic of Côte d'Ivoire(French: République de Côte d'Ivoire), is a country in West Africa. Ivory Coast's de jure capital is Yamoussoukro and the biggest city is the port city of Abidjan.

listen)), officially the Republic of Côte d'Ivoire(French: République de Côte d'Ivoire), is a country in West Africa. Ivory Coast's de jure capital is Yamoussoukro and the biggest city is the port city of Abidjan.

Prior to its colonization by Europeans, Ivory Coast was home to several states, including Gyaaman, the Kong Empire, and Baoulé. There were twoAnyi kingdoms, Indénié and Sanwi, which attempted to retain their separate identity through the French colonial period and after independence.[8] Ivory Coast became a protectorate of France in 1843–44 and was later formed into a French colony in 1893 amid the European scramble for Africa. Ivory Coast achieved independence in 1960, led by Félix Houphouët-Boigny, who ruled the country until 1993. It maintained close political and economic association with its West African neighbours, while at the same time maintaining close ties to the West, especially France. Since the end of Houphouët-Boigny's rule in 1993, Ivory Coast has experienced one coup d'état, in 1999, and two religiously-grounded civil wars: the first taking placebetween 2002 and 2007,[9] and the second during 2010-2011.

Ivory Coast is a republic with a strong executive power invested in itspresident. Through the production of coffee and cocoa, the country was an economic powerhouse in West Africa during the 1960s and 1970s. Ivory Coast went through an economic crisis in the 1980s, contributing to a period of political and social turmoil. The 21st-century Ivorian economy is largely market-based and still relies heavily on agriculture, with smallholder cash-crop production being dominant.[1]

The official language is French, with indigenous local languages also widely used, including Baoulé, Dioula, Dan, Anyin and Cebaara Senufo. The main religions are Islam, Christianity (primarily Roman Catholic) and variousindigenous religions.

Contents

[hide]- 1 Names

- 2 History

- 2.1 Land migration

- 2.2 Pre-Islamic and Islamic periods

- 2.3 Pre-European era

- 2.4 Establishment of French rule

- 2.5 French colonial era

- 2.6 Independence

- 2.7 Houphouët-Boigny administration

- 2.8 Bédié administration

- 2.9 1999 coup

- 2.10 Gbagbo administration

- 2.11 Ivorian Civil War

- 2.12 2010 election

- 2.13 2011 Civil War

- 3 Geography

- 4 Politics

- 5 Economy

- 6 Society

- 7 Culture

- 8 See also

- 9 Notes

- 10 References

- 11 Bibliography

- 12 External links

Names[edit]

Portuguese and French merchant-explorers in the 15th and 16th centuries divided the west coast of Africa, very roughly, into five coasts reflecting local economies. The coast that the French named the Côte d'Ivoire and the Portuguese named the Costa do Marfim—both, literally, being "Ivory Coast"—lay between what was known as the Guiné de Cabo Verde, so-called "Upper Guinea" at Cabo Verde, and Lower Guinea.[10][11] There were also a "Grain Coast", a "Gold Coast", and a "Slave Coast", and, like those three, the name "Ivory Coast" reflected the major trade that occurred on that particular stretch of the coast: the export of ivory.[12][10][13][14][15]

Other names for the coast of ivory included the Côte de Dents,[n 1] literally "Teeth Coast", again reflecting the trade in ivory;[17][18][12][11][15][19] the Côte de Quaqua, after the people that the Dutch named the Quaqua (alternatively Kwa Kwa);[18][10][16] the Coast of the Five and Six Stripes, after a type of cotton fabric also traded there;[18] and the Côte du Vent[n 2], the Windward Coast, after perennial local off-shore weather conditions.[12][10] One can find the name Cote de(s) Dents regularly used in older works.[18] It was used in Duckett's Dictionnaire (Duckett 1853) and by Nicolas Villault de Bellefond, for examples, although Antoine François Prévost used Côte d'Ivoire.[19] In the 19th century it died out in favour of Côte d'Ivoire.[18]

The coastline of the modern state is not quite coterminous with what the 15th- and 16th-century merchants knew as the "Teeth" or "Ivory" coast, which was considered to stretch from Cape Palmas to Cape Three Points and which is thus now divided between the modern states of Ghana and Ivory Coast (with a minute portion of Liberia).[17][13][19][16] But it retained the name through French rule and independence in 1960.[20] The name had long since been translated literally into other languages,[n 3] which the post-independence government considered to be increasingly troublesome whenever its international dealings extended beyond the Francophone sphere. Therefore, in April 1986, the government declared Côte d'Ivoire (or, more fully, République de Côte d'Ivoire[22]) to be its formal name for the purposes of diplomatic protocol, and officially refuses to recognize or accept any translation from French to another language in its international dealings.[21][23][24]

Despite the Ivorian government's request, the English translation "Ivory Coast" (sometimes "the Ivory Coast") is still frequently used in English, by various media outlets and publications.[n 4][n 5]

History[edit]

Main article: History of Ivory Coast

Land migration[edit]

The first human presence in Ivory Coast has been difficult to determine because human remains have not been well preserved in the country's humid climate. However, the presence of newly found weapon and tool fragments (specifically, polished axes cut through shale and remnants of cooking and fishing) has been interpreted as a possible indication of a large human presence during the Upper Paleolithic period (15,000 to 10,000 BC),[30] or at the minimum, the Neolithicperiod.[31]

The earliest known inhabitants of Ivory Coast have left traces scattered throughout the territory. Historians believe that they were all either displaced or absorbed by the ancestors of the present indigenous inhabitants, who migrated south into the area before the 16th century. Such groups included the Ehotilé (Aboisso), Kotrowou (Fresco), Zéhiri (Grand Lahou), Ega and Diès (Divo).[32]

Pre-Islamic and Islamic periods[edit]

The first recorded history is found in the chronicles of North African (Berber) traders, who, from early Roman times, conducted a caravan trade across the Sahara in salt, slaves, gold, and other goods. The southern terminals of the trans-Saharan trade routes were located on the edge of the desert, and from there supplemental trade extended as far south as the edge of the rain forest. The more important terminals—Djenné, Gao, and Timbuctu—grew into major commercial centres around which the great Sudanic empires developed.

By controlling the trade routes with their powerful military forces, these empires were able to dominate neighbouring states. The Sudanic empires also became centres of Islamic education. Islam had been introduced in the western Sudan (today's Mali) by Muslim Berber traders from North Africa; it spread rapidly after the conversion of many important rulers. From the 11th century, by which time the rulers of the Sudanic empires had embraced Islam, it spread south into the northern areas of contemporary Ivory Coast.

The Ghana empire, the earliest of the Sudanic empires, flourished in present-day eastern Mauritania from the fourth to the 13th century. At the peak of its power in the 11th century, its realms extended from the Atlantic Ocean to Timbuctu. After the decline of Ghana, the Mali Empire grew into a powerful Muslim state, which reached its apogee in the early part of the 14th century. The territory of the Mali Empire in Ivory Coast was limited to the north-west corner around Odienné.

Its slow decline starting at the end of the 14th century followed internal discord and revolts by vassal states, one of which,Songhai, flourished as an empire between the fourteenth and sixteenth centuries. Songhai was also weakened by internal discord, which led to factional warfare. This discord spurred most of the migrations of peoples southward toward the forest belt. The dense rain forest, covering the southern half of the country, created barriers to the large-scale political organizations that had arisen in the north. Inhabitants lived in villages or clusters of villages; their contacts with the outside world were filtered through long-distance traders. Villagers subsisted on agriculture and hunting.

Pre-European era[edit]

Five important states flourished in Ivory Coast in the pre-European era. The Muslim Kong Empire was established by the Juula in the early 18th century in the north-central region inhabited by the Sénoufo, who had fled Islamization under theMali Empire. Although Kong became a prosperous center of agriculture, trade, and crafts, ethnic diversity and religious discord gradually weakened the kingdom. The city of Kong was destroyed in 1895 by Samori Ture.

The Abron kingdom of Gyaaman was established in the 17th century by an Akan group, the Abron, who had fled the developing Ashanti confederation of Asanteman in what is present-day Ghana. From their settlement south of Bondoukou, the Abron gradually extended their hegemony over the Dyula people in Bondoukou, who were recent émigrés from the market city of Begho. Bondoukou developed into a major centre of commerce and Islam. The kingdom's Quranicscholars attracted students from all parts of West Africa. In the mid-17th century in east-central Ivory Coast, other Akan groups' fleeing the Asante established a Baoulé kingdom at Sakasso and two Agni kingdoms, Indénié and Sanwi.

The Baoulé, like the Ashanti, developed a highly centralized political and administrative structure under three successive rulers. It finally split into smaller chiefdoms. Despite the breakup of their kingdom, the Baoulé strongly resisted French subjugation. The descendants of the rulers of the Agni kingdoms tried to retain their separate identity long after Ivory Coast's independence; as late as 1969, the Sanwi attempted to break away from Ivory Coast and form an independent kingdom.[33] The current king of Sanwi is Nana Amon Ndoufou V (since 2002).

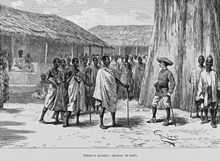

Establishment of French rule[edit]

Compared to neighbouring Ghana, Ivory Coast suffered little from the slave trade, as European slaving and merchant ships preferred other areas along the coast with better harbours. The earliest recorded European voyage to West Africa was made by the Portuguese and took place in 1482. The first West African French settlement, Saint Louis, was founded in the mid-17th century in Senegal while, at about the same time, the Dutch ceded to the French a settlement at Goree Island, offDakar. A French mission was established in 1637 Assinie near the border with the Gold Coast (now Ghana).

Assinie's survival was precarious, however it was not until the mid-19th century that the French were firmly established in Ivory Coast. In 1843–4, French admiral Bouët-Willaumez signed treaties with the kings of the Grand Bassam and Assinie regions, making their territories a French protectorate. French explorers, missionaries, trading companies, and soldiers gradually extended the area under French control inland from the lagoon region. Pacification was not accomplished until 1915.

Activity along the coast stimulated European interest in the interior, especially along the two great rivers, the Senegal and the Niger. Concerted French exploration of West Africa began in the mid-19th century but moved slowly, based more on individual initiative than on government policy. In the 1840s, the French concluded a series of treaties with local West African rulers that enabled the French to build fortified posts along the Gulf of Guinea to serve as permanent trading centres.

The first posts in Ivory Coast included one at Assinie and another at Grand Bassam, which became the colony's first capital. The treaties provided for French sovereignty within the posts, and for trading privileges in exchange for fees or coutumes paid annually to the local rulers for the use of the land. The arrangement was not entirely satisfactory to the French, because trade was limited and misunderstandings over treaty obligations often arose. Nevertheless, the French government maintained the treaties, hoping to expand trade.

France also wanted to maintain a presence in the region to stem the increasing influence of the British along the Gulf of Guinea coast. The French built naval bases to keep out non-French traders and began a systematic conquest of the interior. (They accomplished this only after a long war in the 1890s against Mandinka forces, mostly from Gambia. Guerrilla warfare by the Baoulé and other eastern groups continued until 1917).[citation needed]

The defeat of France in the Franco-Prussian War in 1871 and the subsequent annexation by Germany of the French province of Alsace Lorraine caused the French government to abandon its colonial ambitions and withdraw its military garrisons from its French West African trading posts, leaving them in the care of resident merchants. The trading post at Grand Bassam in Ivory Coast was left in the care of a shipper from Marseille, Arthur Verdier, who in 1878 was namedResident of the Establishment of Ivory Coast.[33]

In 1886, to support its claims of effective occupation, France again assumed direct control of its West African coastal trading posts and embarked on an accelerated program of exploration in the interior. In 1887 Lieutenant Louis Gustave Binger began a two-year journey that traversed parts of Ivory Coast's interior. By the end of the journey, he had concluded four treaties establishing French protectorates in Ivory Coast. Also in 1887, Verdier's agent, Marcel Treich-Laplène, negotiated five additional agreements that extended French influence from the headwaters of the Niger River Basin through Ivory Coast.

French colonial era[edit]

By the end of the 1880s, France had established what passed for control over the coastal regions of Ivory Coast, and in 1889 Britain recognized French sovereignty in the area. That same year, France named Treich-Laplène titular governor of the territory. In 1893 Ivory Coast was made a French colony, and then Captain Binger was appointed governor. Agreements with Liberia in 1892 and with Britain in 1893 determined the eastern and western boundaries of the colony, but the northern boundary was not fixed until 1947 because of efforts by the French government to attach parts of Upper Volta (present-day Burkina Faso) and French Sudan (present-day Mali) to Ivory Coast for economic and administrative reasons.

France's main goal was to stimulate the production of exports. Coffee, cocoa and palm oil crops were soon planted along the coast. Ivory Coast stood out as the only West African country with a sizeable population of settlers; elsewhere in West and Central Africa, the French and British were largely bureaucrats.[citation needed] As a result, French citizens owned one third of the cocoa, coffee and bananaplantations and adopted a forced-labour system.

Throughout the early years of French rule, French military contingents were sent inland to establish new posts. Some of the native population resisted French penetration and settlement. Among those offering greatest resistance was Samori Ture, who in the 1880s and 1890s was establishing the Wassoulou Empire, which extended over large parts of present-day Guinea, Mali, Burkina Faso, and Ivory Coast. Samori Ture's large, well-equipped army, which could manufacture and repair its own firearms, attracted strong support throughout the region. The French responded to Samori Ture's expansion of regional control with military pressure. French campaigns against Samori Ture, which were met with fierce resistance, intensified in the mid-1890s until he was captured in 1898.

France's imposition of a head tax in 1900 to support the colony in a public works program, provoked a number of revolts. Ivoirians viewed the tax as a violation of the terms of the protectorate treaties, because they thought that France was demanding the equivalent of a coutume from the local kings, rather than the reverse. Much of the population, especially in the interior, considered the tax a humiliating symbol of submission.[34] In 1905, the French officially abolished slavery in most of French West Africa.[35]

From 1904 to 1958, Ivory Coast was a constituent unit of the Federation of French West Africa. It was a colony and an overseas territory under the Third Republic. In World War I Ivory Coast was put into a bad position with the German invasion threatened in 1914. But after France made regiments from Ivory Coast to fight in France. Coloney resources were rationed from 1917-1919. Some 150,000 men from Ivory Coast died in World War I. Until the period following World War II, governmental affairs in French West Africa were administered from Paris. France's policy in West Africa was reflected mainly in its philosophy of "association", meaning that all Africans in Ivory Coast were officially French "subjects", but without rights to representation in Africa or France.

French colonial policy incorporated concepts of assimilation and association. Based on an assumption of the superiority of French culture over all others, in practice the assimilation policy meant extension of the French language, institutions, laws, and customs in the colonies. The policy of association also affirmed the superiority of the French in the colonies, but it entailed different institutions and systems of laws for the colonizer and the colonized. Under this policy, the Africans in Ivory Coast were allowed to preserve their own customs insofar as they were compatible with French interests.

An indigenous elite trained in French administrative practice formed an intermediary group between the French and the Africans. Assimilation was practiced in Ivory Coast to the extent that after 1930, a small number of Westernized Ivoirians were granted the right to apply for French citizenship. Most Ivoirians, however, were classified as French subjects and were governed under the principle of association.[36] As subjects of France, they had no political rights. They were drafted for work in mines, on plantations, as porters, and on public projects as part of their tax responsibility. They were expected to serve in the military and were subject to the indigénat, a separate system of law.[37]

In World War II, the Vichy regime remained in control until 1942,when British troops invaded without much resistance. Winston Churchill gave the power back to members of General Charles de Gaulle's provisional government. By 1943 the Allies had returned French West Africa back to the French. The Brazzaville Conference of 1944, the first Constituent Assembly of the Fourth Republic in 1946, and France's gratitude for African loyalty during World War II led to far-reaching governmental reforms in 1946. French citizenship was granted to all African "subjects," the right to organize politically was recognized, and various forms of forced labour were abolished.

Until 1958, governors appointed in Paris administered the colony of Ivory Coast, using a system of direct, centralized administration that left little room for Ivoirian participation in policy making. Whereas British colonial administration adopted divide-and-rule policies elsewhere, applying ideas of assimilation only to the educated elite, the French were interested in ensuring that the small but influential elite was sufficiently satisfied with the status quo to refrain from any anti-French sentiment. Although strongly opposed to the practices of association, educated Ivoirians believed that they would achieve equality with their French peers through assimilation rather than through complete independence from France. But, after the assimilation doctrine was implemented entirely through the postwar reforms, Ivoirian leaders realized that even assimilation implied the superiority of the French over the Ivoirians, and that discrimination and political inequality would end only with independence.[38]

No comments:

Post a Comment