here is a huge connection between the Smithsonian Inst.................and spying......................

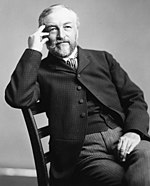

Samuel Pierpont Langley

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Samuel Pierpont Langley | |

|---|---|

Samuel Pierpont Langley

| |

| Born | August 22,

1834 Roxbury, Massachusetts |

| Died | February 27, 1906

(aged 71) Aiken, South Carolina |

| Nationality | United States |

| Fields | Astronomy Aviation |

| Known for | Solar physics |

| Notable awards | Rumford Medal (1886)Henry Draper Medal (1886)Janssen Medal (1893)[1][2] |

Contents

[hide]Allegheny Observatory[edit]

Langley arrived in Pittsburgh in 1867 to become the first director of the Allegheny Observatory, after the institution had fallen into hard times and been given to the Western University of Pennsylvania. By then, the department was in disarray – equipment was broken, there was no library and the building needed repairs. Through the friendship and aid of William Thaw, a Pittsburgh industrial leader, Langley was able to improve the observatory equipment and build additional apparati. One of the new instruments was a small transit telescope used to observe the position of the stars as they cross the celestial meridian.[3] He raised money for the department in large part by distributing standard time to cities and railroads. Up until then, correct time had only occasionally been sent from American observatories for public use. Clocks were manually wound in those days and time tended to be imprecise. Exact time had not been especially necessary. It was enough to know that at noon the sun was directly above the head. All that until railroad tracks were installed.As railroads became operational, that unpredictability of time became dangerous. Trains ran by a published schedule, but the scheduling was chaotic. If the watches of an engineer and a switch operator differed by even a minute or two, it could mean disaster. Two trains could be on the same track at the same time and crash.

Using astronomical observations obtained from the new telescope, Langley devised a precise time standard – including time zones – that became known as the Allegheny Time System. Initially he broadcast time signals to Allegheny city business and the Pennsylvania Railroad. Eventually, twice a day, the Allegheny time signals broadcast the correct time via 4713 miles of telegraph lines to all railroads in the US and Canada. Langley used the money from the railroads to finance the observatory. From about 1868, revenues from the Allegheny Time continued to fund the observatory until the US Naval Observatory provided the signals for free in 1883.

Once funding was secure, Langley devoted his time at the Observatory initially in researching the sun. He used his draftsman skills (from his first job right out of high school) to produce hundreds of drawings of solar phenomena, many of which were the first the world had seen. His 1873 remarkably detailed illustration of a sun spot, observed while using the observatory's 13-inch Fitz-Clark refractor became a classic. It is featured on page 21 of his book, The New Astronomy, but was also widely reprinted – in the Americas as well as throughout Europe.

In 1886, Langley received the inaugural Henry Draper Medal from the National Academy of Sciences for his contributions to solar physics.[4] His publication in 1890 of infrared observations at the Allegheny Observatory in Pittsburgh together with Frank Washington Very along with the data he collected from his invention, the bolometer, was used by Svante Arrhenius to make the first calculations on the greenhouse effect.

Aviation work[edit]

Langley attempted to make a working piloted heavier-than-air aircraft. His models flew, but his two attempts at piloted flight were not successful. Langley began experimenting with rubber-band powered models and gliders in 1887. (According to one book, he was not able to reproduce Alphonse Pénaud's time aloft with rubber power but persisted anyway.) He built a rotating arm (functioning like a wind tunnel) and made larger flying models powered by miniature steam engines. Langley realised that sustained powered flight was possible when he found that a 1 lb. brass plate suspended from the rotating arm by a spring, could be kept aloft by a spring tension of less than 1 oz.He met the writer Rudyard Kipling around this time, who described one of Langley's experiments in his autobiography:

Through Roosevelt I met Professor Langley of the Smithsonian, an old man who had designed a model aeroplane driven—for petrol had not yet arrived—by a miniature flash-boiler engine, a marvel of delicate craftsmanship. It flew on trial over two hundred yards, and drowned itself in the waters of the Potomac, which was cause of great mirth and humour to the Press of his country. Langley took it coolly enough and said to me that, though he would never live till then, I should see the aeroplane established.[5]

No comments:

Post a Comment