Life[edit]

Early years (1805–27)[edit]

Main article: Early life of Joseph Smith

Joseph Smith, Jr. was born on December 23, 1805, in Sharon, Vermont, to Lucy Mack Smith and her husband Joseph, a merchant and farmer.[6] After suffering a crippling bone infection when he was seven, the younger Smith hobbled around on crutches for three years.[7] In 1816–17, after an ill-fated business venture and three years of crop failures, the Smith family moved to the western New York village of Palmyra, and eventually took a mortgage on a 100-acre (40 ha) farm in the nearby town of Manchester.

During the Second Great Awakening, the region was a hotbed of religious enthusiasm; and between 1817 and 1825, there were several camp meetings and revivals in the Palmyra area.[8] Although Smith's parents disagreed about religion, the family was caught up in this excitement.[9] Smith later said he became interested in religion at about the age of twelve; without doubt, he participated in church classes and read the Bible. As a teenager, he may have been sympathetic to Methodism.[10] With other family members, Smith also engaged in religious folk magic, not an uncommon practice at the time.[11] Both his parents and his maternal grandfather reportedly had visions or dreams that they believed communicated messages from God.[12] Smith said that although he had become concerned about the welfare of his soul, he was confused by the claims of competing religious denominations.[13]

Years later Smith said that in 1820 he had received a vision that resolved his religious confusion.[14] While praying in a wooded area near his home, he said that God, in a vision, had told him his sins were forgiven and that all contemporary churches had "turned aside from the gospel."[15] Smith said he told the experience to a preacher, who dismissed the story with contempt; but the experience was largely unknown, even to most Mormons, until the 1840s.[16] Although Smith may have understood the event as a personal conversion, this "First Vision" later grew in importance among Mormons, who today see it as the founding event of Mormonism.[17]

Smith said that in 1823 while praying one night for forgiveness from his sins, he was visited by an angel named Moroni, who revealed the location of a buried book made of golden plates, as well as other artifacts, including a breastplate and a set of interpreters composed of two seer stones set in a frame, which had been hidden in a hill in Manchester near his home.[18] Smith said he attempted to remove the plates the next morning but was unsuccessful because the angel prevented him.[19] Smith reported that during the next four years, he made annual visits to the hill but each time returned without the plates.[20]

Meanwhile, the Smith family faced financial hardship due in part to the November 1823 death of Smith's oldest brother Alvin, who had assumed a leadership role in the family.[21] Family members supplemented their meager farm income by hiring out for odd jobs and working as treasure seekers, a type of magical supernaturalism common during the period.[22] Smith was said to have an ability to locate lost items by looking into a seer stone, which he also used in treasure hunting, including several unsuccessful attempts to find buried treasure sponsored by a wealthy farmer in Chenango County, New York.[23] In 1826, Smith was brought before a Chenango County court for "glass-looking", or pretending to find lost treasure.[24] The result of the proceeding remains unclear as primary sources report various conflicting outcomes.[25]

While boarding at the Hale house in Harmony, Pennsylvania, Smith met and began courting Emma Hale. When Smith proposed marriage, Emma's father Isaac Hale objected because Smith was "a stranger" without a proven reputation and had no means of supporting his daughter other than money digging.[26] Smith and Emma eloped and were married on January 18, 1827, after which the couple began boarding with Smith's parents in Manchester. Later that year, when Smith promised to abandon treasure seeking, Hale offered to let the couple to live on his property in Harmony and help Smith get started in business.[27]

Smith said that he made his last annual visit to the hill on September 22, 1827, taking Emma with him.[28] This time, he said he retrieved the plates and put them in a locked chest. He said the angel commanded him not to show the plates to anyone else but to publish their translation, reputed to be the religious record of indigenous Americans.[29] Although Smith had left his treasure hunting company, his former associates believed he had double-crossed them by taking for himself what they considered joint property.[30]After they ransacked places where a competing treasure-seer said the plates were hidden, Smith decided to leave Palmyra.[31]

Founding a church (1827–30)[edit]

Main article: Life of Joseph Smith from 1827 to 1830

In October 1827, Smith and his pregnant wife moved from Palmyra to Harmony (now Oakland), Pennsylvania, aided by money from a relatively prosperous neighbor, Martin Harris.[32] Living near his in-laws, Smith transcribed some characters that he said were engraved on the plates, and then dictated a translation to his wife.[33]

In February 1828, Martin Harris arrived to assist Smith by transcribing his dictation. Harris also took a sample of the characters to a few prominent scholars, including Charles Anthon, who Harris said initially authenticated the characters and their translation but then retracted his opinion after learning that Smith was supposed to have received the plates from an angel.[34] Anthon denied Harris's account of the meeting, claiming instead that he had tried to convince Harris that he had been the victim of a fraud. Nevertheless, Harris returned to Harmony in April 1828, encouraged to continue as Smith's scribe.[35]

Smith continued to dictate to Harris until mid-June 1828, when Harris began having doubts about the project, fueled in part by his wife's skepticism. Harris convinced Smith to let him take the existing 116 pages of manuscript to Palmyra to show a few family members, including his wife.[36] Harris lost the manuscript—of which there was no other copy—at about the same time as Smith's wife Emma gave birth to a stillborn son.[37] Smith said that as punishment for losing the manuscript the angel took away the plates and revoked his ability to translate. During this dark period Smith briefly attended Methodist meetings with his wife until a cousin of hers objected to inclusion of a "practicing necromancer" on the Methodist class roll.[38]

Smith said that the angel returned the plates to him on September 22, 1828,[39] and he resumed dictation in April 1829, after he met Oliver Cowdery, who replaced Harris as his scribe.[40] They worked full time on the manuscript between April and early June 1829, and then moved to Fayette, New York, where they continued to work at the home of Cowdery's friend Peter Whitmer.[41] When the narrative described an institutional church and a requirement for baptism, Smith and Cowdery baptized each other.[42] Dictation was completed around July 1, 1829.[43]

Although Smith had previously refused to show the plates to anyone, he told Martin Harris, Oliver Cowdery, and David Whitmer that they would be allowed to see them.[44] These men, known collectively as the Three Witnesses—along with a later group of Eight Witnesses composed of male members of the Whitmer and Smith families—signed statements testifying that they had seen the golden plates; the eight witnesses also said they had actually handled the plates.[45] According to Smith, the angel Moroni took back the plates once Smith finished using them.

The completed work, the Book of Mormon, was published in Palmyra on March 26, 1830, by printer E. B. Grandin, Martin Harris having mortgaged his farm to finance it. Soon after, on April 6, 1830, Smith and his followers formally organized the Church of Christ, and small branches were established in Palmyra, Fayette, and Colesville, New York.[46] The Book of Mormon brought Smith regional notoriety and opposition from those who remembered his money-digging and the 1826 Chenango County trial.[47] After Cowdery baptized several new members, the Mormons received threats of mob violence; and before Smith could confirm the newly baptized members, he was arrested and brought to trial as a disorderly person.[48] He was acquitted, but both he and Cowdery had to flee Colesville to escape a gathering mob. In probable reference to this period of flight, Smith said that Peter, James, and John had appeared to him and had ordained him and Cowdery to a higher priesthood.[49]

Smith's authority was undermined when Oliver Cowdery, Hiram Page, and other church members also claimed to receive revelations.[50] In response, Smith dictated a revelation which clarified his office as a prophet and an apostle and which declared that only he held "the keys of the mysteries, and the revelations" with the ability to inscribe scripture for the church.[51] Shortly after the conference, Smith dispatched Cowdery, Peter Whitmer, and others on a mission to proselytize Native Americans.[52] Cowdery was also assigned the task of locating the site of the New Jerusalem.[53]

On their way to Missouri, Cowdery's party passed through northeastern Ohio, where Sidney Rigdon and over a hundred followers of his variety of Campbellite Restorationism converted to Mormonism, more than doubling the size of the church.[54] Rigdon soon visited New York and quickly became Smith's primary assistant.[55] With growing opposition in New York, Smith gave forth as revelation that Kirtland was the eastern boundary of the New Jerusalem and that his followers must gather there.[56]

Life in Ohio (1831–38)[edit]

Main articles: Life of Joseph Smith from 1831 to 1834 and Life of Joseph Smith from 1834 to 1837

When Smith moved to Kirtland, Ohio, in January 1831, he encountered a religious culture that included enthusiastic demonstrations of spiritual gifts, including fits and trances, rolling on the ground, and speaking in tongues.[57] Smith tamed these outbursts by producing two revelations that brought the Kirtland congregation under his own authority. Rigdon's followers had also been practicing a form of communalism, and this Smith adopted, calling it the United Order.[58] Smith had promised church elders that in Kirtland they would receive an endowment of heavenly power, and at the June 1831 general conference, he introduced the greater authority of a High ("Melchizedek") Priesthood to the church hierarchy.[59]

Converts poured into Kirtland. By the summer of 1835, there were fifteen hundred to two thousand Mormons in the vicinity, many expecting Smith to lead them shortly to the Millennial kingdom.[60] Though the mission to the Indians had been a failure, the missionaries sent on their way by a government Indian agent, Cowdery reported that he had found the site of the New Jerusalem in Jackson County, Missouri.[61] After Smith visited in July 1831, he agreed, pronouncing the frontier hamlet of Independence the "center place" of Zion.[62] Nevertheless, Rigdon disapproved, and for most of the 1830s the church remained divided between Ohio and Missouri.[63] Smith continued to live in Ohio, but visited Missouri again in early 1832 in order to prevent a rebellion of prominent church members, including Cowdery, who believed the church in Missouri was being neglected.[64] Smith's trip was hastened by a mob of Ohio residents who were incensed over the United Order and Smith's political power; the mob beat Smith and Rigdon unconscious, tarred and feathered them, and left them for dead.[65]

In Jackson County, Missouri residents resented the Mormon newcomers for both political and religious reasons.[66] Tension increased until July 1833, when non-Mormons forcibly evicted the Mormons and destroyed their property. Smith advised them to bear the violence patiently until they were attacked a fourth time, after which they could fight back.[67] After armed bands exchanged fire and one Mormon and two non-Mormons were killed, the old settlers brutally expelled the Mormons from the county.[68]

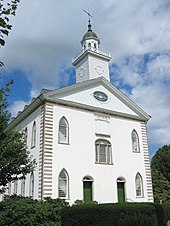

Smith ended the communitarian experiment and changed the name of the church to the "Church of Latter Day Saints" before leading a small paramilitary expedition, later called Zion's Camp, to aid the Missouri Mormons.[69] As a military endeavor, the expedition was a failure; the men were outnumbered and suffered from dissension and a cholera outbreak.[70] Nevertheless, Zion's Camp transformed Mormon leadership, and many future church leaders came from among the participants.[71] After the Camp returned, Smith drew heavily from its participants to establish five governing bodies in the church, all originally of equal authority to check one another; among these five groups was a quorum of twelve apostles.[72] Smith gave a revelation saying that to redeem Zion, his followers would have to receive an endowment in the Kirtland Temple,[73] and in March 1836, at the temple's dedication, many participants in the promised endowment saw visions of angels, spoke in tongues, and prophesied.[74]

In late 1837, a series of internal disputes led to the collapse of the Kirtland Mormon community.[75] Smith was blamed for having promoted a church-sponsored bank that failed and accused of engaging in a sexual relationship with his serving girl, Fanny Alger.[76] Building the temple had left the church deeply in debt, and Smith was hounded by creditors.[77] Having heard of a large sum of money supposedly hidden in Salem, Massachusetts, Smith traveled there and received a revelation that God had "much treasure in this city".[78] But after a month, he returned to Kirtland empty-handed.[79]

In January 1837, Smith and other church leaders created a joint stock company, called the Kirtland Safety Society, to act as a quasi-bank. The company issued bank notes capitalized in part by real estate.[80] Smith encouraged the Latter Day Saints to buy the notes and invested heavily in them himself, but the bank failed within a month.[81] As a result, the Latter Day Saints in Kirtland suffered intense pressure from debt collectors and severe price volatility. Smith was held responsible for the failure, and there were widespread defections from the church, including many of Smith's closest advisers.[82] After a warrant was issued for Smith's arrest on a charge of banking fraud, Smith and Rigdon fled Kirtland for Missouri on the night of January 12, 1838.[83]

No comments:

Post a Comment