IRAN-IRAQ WAR

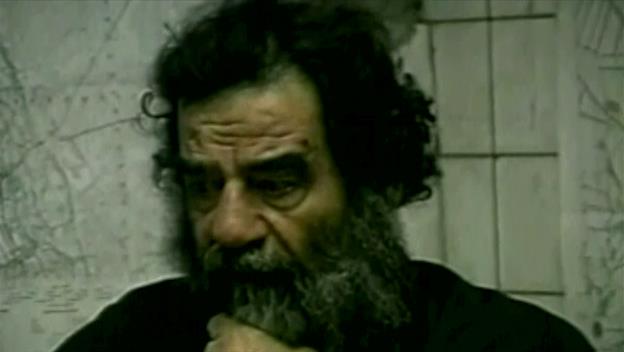

The protracted war between these neighboring Middle Eastern countries resulted in at least half a million casualties and several billion dollars’ worth of damages, but no real gains by other side. Started by Iraq dictator Saddam Hussein in September 1980, the war was marked by indiscriminate ballistic-missile attacks, extensive use of chemical weapons and attacks on third-country oil tankers in the Persian Gulf. Although Iraq was forced on the strategic defensive, Iran was unable to reconstitute effective armored formations for its air force and could not penetrate Iraq’s borders deeply enough to achieve decisive results. The end came in July 1988 with the acceptance UN Resolution 598.

During the eight years between Iraq’s formal declaration of war on September 22, 1980, and Iran’s acceptance of a cease-fire with effect on July 20, 1988, at the very least half a million and possibly twice as many troops were killed on both sides, at least half a million became permanent invalids, some 228 billion dollars were directly expended, and more than 400 billion dollars of damage (mostly to oil facilities, but also to cities) was inflicted, mostly by artillery barrages. Aside from that, the war was inconsequential: having won Iranian recognition of exclusive Iraqi sovereignty over the Shatt-el-Arab River (into which the Tigris and Euphrates combine, forming Iraq’s best outlet to the sea), in 1988 Saddam Hussein surrendered that gain when in need of Iran’s neutrality in anticipation of the 1991 Gulf War.

Three things distinguish the Iran-Iraq War. First, it was inordinately protracted, lasting longer than either world war, essentially because Iran did not want to end it, while Iraq could not. Second, it was sharply asymmetrical in the means employed by each side, because though both sides exported oil and purchased military imports throughout, Iraq was further subsidized and supported by Kuwait and Saudi Arabia, allowing it to acquire advanced weapons and expertise on a much larger scale than Iran. Third, it included three modes of warfare absent in all previous wars since 1945: indiscriminate ballistic-missile attacks on cities by both sides, but mostly by Iraq; the extensive use of chemical weapons (mostly by Iraq); and some 520 attacks on third-country oil tankers in the Persian Gulf-for which Iraq employed mostly manned aircraft with antishipping missiles against tankers lifting oil from Iran’s terminals, while Iran used mines, gunboats, shore-launched missiles, and helicopters against tankers lifting oil from the terminals of Iraq’s Arab backers.

When Saddam Hussein, president of Iraq, quite deliberately started the war, he miscalculated on two counts: first, in attacking a country greatly disorganized by revolution but also greatly energized by it-and whose regime could be consolidated only by a long “patriotic” war, as with all revolutionary regimes; and second, at the level of theater strategy, in launching a surprise invasion against a very large country whose strategic depth he was not even trying to penetrate. Had Iran been given ample warning, it would have mobilized its forces to defend its borderlands; that would have made the Iraqi invasion much more difficult, but in the process the bulk of Iranian forces might have been defeated, possibly forcing Iran to accept a cease-fire on Iraqi terms. As it was, the initial Iraqi offensive thrusts landed in the void, encountering only weak border units before reaching their logistical limits. At that point, Iran had only just started to mobilize in earnest.

From then on, until the final months of the war eight years later, Iraq was forced on the strategic defensive, having to face periodic Iranian offensives on one sector or another, year after year. After losing most of his territorial gains by May 1982 (when Iran recaptured Khorramshahr), Saddam Hussein’s strategic response was to proclaim a unilateral cease-fire (June 10, 1982) while ordering Iraqi forces to withdraw to the border. But Iran rejected a cease-fire, demanding the removal of Saddam Hussein and compensation for war damage. Upon Iraq’s refusal, Iran launched an invasion into Iraqi territory (Operation Ramadan, on July 13, 1982) in the first of many attempts over the coming years to conquer Basra, Iraq’s second city and only real port.

But revolutionary Iran was very limited in its tactically offensive means. Cut off from U.S. supplies for its largely U.S.-equipped forces and deprived of the shah’s officer cadres who had been driven into exile, imprisoned, or killed, it never managed to reconstitute effective armored formations or its once large and modern air force. Iran’s army and Pasdaran revolutionary guards could mount only massed infantry attacks supported by increasingly strong artillery fire. They capitalized on Iran’s morale and population advantage (forty million versus Iraq’s thirteen million), but although foot infantry could breach Iraqi defense lines from time to time, if only by costly human-wave attacks, it could not penetrate deeply enough in the aftermath to achieve decisive results.

By 1988 Iran was demoralized by the persistent failure of its many “final” offensives over the years, by the prospect of unending casualties, by its declining ability to import civilian goods as well as military supplies, and by the Scud missile attacks on Teheran. But what finally ended the war was Iraq’s belated reversion to main-force offensive action on the ground. Having long conserved its forces and shifted to all-mechanized configurations to circumvent the reluctance of its troops to face enemy fire, Iraq attacked on a large scale in April 1988. The end came on July 18, when Iran accepted UN Resolution 598 calling for an immediate cease-fire, though minor Iraqi attacks continued for a few more days after the truce came into effect on July 20, 1988.

The Reader’s Companion to Military History. Edited by Robert Cowley and Geoffrey Parker. Copyright © 1996 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

No comments:

Post a Comment