Indo-European languages

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

"Indo-European" redirects here. For other uses, see Indo-European (disambiguation).

See also: List of Indo-European languages

| Indo-European | |

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution: | Before the 16th century, Europe, South,Central and Southwest Asia; today worldwide. |

| Linguistic classification: | One of the world's major language families |

| Proto-language: | Proto-Indo-European |

| Subdivisions: |

|

| ISO 639-2 / 5: | ine |

| Glottolog: | indo1319[1] |

Countries with a majority of speakers of IE languages

Countries with an IE minority language with official status

| |

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

The Indo-European languages are a family of several hundred related languages and dialects. There are about 439 languages and dialects, according to the 2009 Ethnologue estimate, about half (221) belonging to the Indo-Aryan subbranch.[2] It includes most major current languages of Europe, South Asia, parts of theMiddle East and Central Asia, and was also predominant in ancient Anatolia. With written attestations appearing since the Bronze Age in the form of the Anatolian languages and Mycenaean Greek, the Indo-European family is significant to the field of historical linguistics as possessing the second-longest recorded history, after the Afro-Asiatic family.

Indo-European languages are spoken by almost 3 billion native speakers,[3] the largest number by far for any recognised language family. Of the 20 languages with the largest numbers of native speakers according to SIL Ethnologue, 11 are Indo-European: Spanish, English, Hindi, Portuguese, Bengali, Russian, Lahnda,German, French, Marathi, and Urdu, accounting for over 1.7 billion native speakers.[4] Several disputed proposals link Indo-European to other major language families.

Contents

[hide]Etymology[edit]

Thomas Young coined the term "Indo-European" in 1813, from Indo- + European, after the geographical extremes of the language family: from Western Europe toNortheast India.[5]

History of Indo-European linguistics[edit]

Main article: Indo-European studies

In the 16th century, European visitors to the Indian Subcontinent began to suggest similarities between Indo-Aryan, Iranian and European languages. In 1583, Thomas Stephens, an English Jesuit missionary in Goa, in a letter to his brother that was not published until the 20th century,[6] noted similarities between Indian languages, specifically Sanskrit, and Greek and Latin.

Another account to mention the ancient language Sanskrit came from Filippo Sassetti (born in Florence in 1540), a merchant who travelled to the Indian subcontinent. Writing in 1585, he noted some word similarities between Sanskrit and Italian (these included devaḥ/dio "God", sarpaḥ/serpe "serpent", sapta/sette "seven", aṣṭa/otto "eight", nava/nove "nine").[6] However, neither Stephens's nor Sassetti's observations led to further scholarly inquiry.[6]

In 1647, Dutch linguist and scholar Marcus Zuerius van Boxhorn noted the similarity among Indo-European languages, and supposed that they derived from a primitive common language he called Scythian. He included in his hypothesis Dutch, Albanian, Greek, Latin, Persian, and German, later adding Slavic, Celtic, and Baltic languages. However, Van Boxhorn's suggestions did not become widely known and did not stimulate further research.

The Ottoman Turkish traveller Evliya Çelebi, who visited Vienna in 1665-66 as part of a diplomatic mission, noted a few similarities between words in German and Farsi. Gaston Coeurdoux and others made observations of the same type. Coeurdoux made a thorough comparison of Sanskrit, Latin and Greek conjugations in the late 1760s to suggest a relationship between them. Similarly, Mikhail Lomonosov compared different language groups of the world including Slavic, Baltic ("Kurlandic"), Iranian ("Medic"), Finnish, Chinese, "Hottentot", and others. He emphatically expressed the antiquity of the linguistic stages accessible to comparative method in the drafts for his Russian Grammar (published 1755).[7]

The hypothesis reappeared in 1786 when Sir William Jones first lectured on the striking similarities between three of the oldest languages known in his time: Latin, Greek, and Sanskrit, to which he tentatively added Gothic, Celtic, and Persian,[8] though his classification contained some inaccuracies and omissions.[9]

It was Thomas Young who in 1813[10] first used the term Indo-European, which became the standard scientific term through the work of Franz Bopp, whose systematic comparison of these and other old languages supported the hypothesis. A synonym for "Indo-European" is Indo-Germanic (Idg. or IdG.), which defines the family by indicating its southeasternmost and northwesternmost branches. In most languages this term is dated or less common, whereas in German it is still the standard scientific term.[11] Advocates of Indo-Germanic often claim that "Indo-European" is misleading because many historic and several living European languages (the unrelated Uralic languages, as well as several others, are also spoken in Europe) do not belong to this family. Advocates of Indo-European counter that Indo-Germanic is misleading because many of the European languages included are not in fact Germanic.

Franz Bopp's Comparative Grammar, which appeared between 1833 and 1852, is the beginning of Indo-European studies as an academic discipline. The classical phase of Indo-European comparative linguistics leads from this work to August Schleicher's 1861 Compendium and up to Karl Brugmann's Grundriss, published in the 1880s. Brugmann's junggrammatische reevaluation of the field and Ferdinand de Saussure's development of the laryngeal theory may be considered the beginning of "modern" Indo-European studies. The generation of Indo-Europeanists active in the last third of the 20th century (such as Calvert Watkins, Jochem Schindler and Helmut Rix) developed a better understanding of morphology and, in the wake of Kuryłowicz's 1956 Apophonie, understanding of the ablaut.

Classification[edit]

The various subgroups of the Indo-European language family include ten major branches, given in the chronological order of their emergence according to David Anthony:[12]

- Anatolian (Asia Minor), the earliest attested branch. Emerged around 4200 BCE.[12] Isolated terms in Luwian/Hittite mentioned in Semitic Old Assyrian texts from the 20th and 19th centuries BC, Hittite texts from about 1650 BC;[13][14] extinct by Late Antiquity.

- Tocharian, emerged around 3700 BCE,[12] extant in two dialects (Turfanian and Kuchean), attested from roughly the 6th to the 9th century AD. Marginalized by the Old Turkic Uyghur Khaganate and probably extinct by the 10th century.

- Germanic (from Proto-Germanic), emerged around 3300 BCE,[12] earliest testimonies in runic inscriptions from around the 2nd century AD, earliest coherent texts in Gothic, 4th century AD. Old English manuscript tradition from about the 8th century AD.

- Italic, including Latin and its descendants (the Romance languages), emerged around 3000 BCE,[12] attested from the 7th century BC.

- Celtic, descended from Proto-Celtic, emerged around 3000 BCE.[12] Gaulish inscriptions date as early as the 6th century BC; Celtiberian from the 2nd century BC; Primitive Irish Ogham inscriptions 5th century AD, earliest inscriptions in Old Welsh from the 8th Century AD.

- Armenian, emerged around 2800 BCE.[12] Alphabet writings known from the beginning of the 5th century AD.

- Balto-Slavic, emerged around 2800 BCE,[12] believed by most Indo-Europeanists[15] to form a phylogenetic unit, while a minority ascribes similarities to prolonged language contact.

- Slavic (from Proto-Slavic), attested from the 9th century AD (possibly earlier; see Slavic runes), earliest texts in Old Church Slavonic.

- Baltic, attested from the 14th century AD; for languages attested that late, they retain unusually many archaic features attributed to Proto-Indo-European (PIE).

- Hellenic, emerged around 2500 BCE.[12] Fragmentary records in Mycenaean Greek from between 1450 and 1350 BC have been found.[16] Homeric texts date to the 8th century BC. (See Proto-Greek, History of Greek.)

- Indo-Iranian, emerged around 2200 BCE,[12] attested circa 1400 BC, descended from Proto-Indo-Iranian (dated to the late 3rd millennium BC).

- Indo-Aryan or 'Indic languages', attested from around 1400 BC in Hittite texts from Asia Minor, showing traces of Indo-Aryan words.[17][18] Epigraphically from the 3rd century BC in the form of Prakrit (Edicts of Ashoka). The Rigveda is assumed to preserve intact records via oral tradition dating from about the mid-2nd millennium BC in the form of Vedic Sanskrit.

- Iranian or Iranic, attested from roughly 1000 BC in the form of Avestan. Epigraphically from 520 BC in the form of Old Persian (Behistun inscription).

- Dardic

- Nuristani

- Albanian, attested from the 14th century AD; Proto-Albanian language likely evolved from Paleo-Balkan predecessors.[19][20]

In addition to the classical ten branches listed above, several extinct and little-known languages have existed:

- Illyrian — possibly related to Messapian, Albanian, or both

- Venetic — close to Italic and possibly Continental Celtic

- Liburnian — doubtful affiliation, features shared with Venetic, Illyrian and Indo-Hittite, significant transition of the Pre-Indo-European elements

- Messapian — not conclusively deciphered

- Phrygian — language of the ancient Phrygians, possibly close to Thracian, Armenian, Greek[citation needed]

- Paionian — extinct language once spoken north of Macedon

- Thracian — possibly including Dacian

- Dacian — possibly very close to Thracian

- Ancient Macedonian — proposed relationships to Greek, Illyrian, Thracian, and Phrygian.

- Ligurian — possibly close to or part of Celtic.[21]

- Sicel - an ancient language spoken by the Sicels (Greek Sikeloi, Latin Siculi), one of the three indigenous (i.e., pre-Greek and pre-Punic) tribes of Sicily. Proposed relationship to Latin or proto-Illyrian (Pre-Indo-European) at an earlier stage.[22]

- Lusitanian — possibly related to (or part of) Celtic, Ligurian, or Italic

- Cimmerian – possibly Iranic, Thracian, or Celtic

Grouping[edit]

Further information: Language families

Membership of these languages in the Indo-European language family is determined by genetic relationships, meaning that all members are presumed descendants of a common ancestor, Proto-Indo-European. Membership in the various branches, groups and subgroups or Indo-European is also genetic, but here the defining factors are shared innovations among various languages, suggesting a common ancestor that split off from other Indo-European groups. For example, what makes the Germanic languages a branch of Indo-European is that much of their structure and phonology can so be stated in rules that apply to all of them. Many of their common features are presumed innovations that took place in Proto-Germanic, the source of all the Germanic languages.

Tree versus wave model[edit]

See also: Language change

To the evolutionary history of a language family, a genetic "tree model" is considered appropriate especially if communities do not remain in effective contact as their languages diverge. Exempted from this concept are shared innovations acquired by borrowing (or other means of convergence), that cannot be considered genetic. In this case the so-called "wave model" applies, featuring borrowings and no clear underlying genetic tree. It has been asserted, for example, that many of the more striking features shared by Italic languages (Latin, Oscan, Umbrian, etc.) might well be areal features. More certainly, very similar-looking alterations in the systems of long vowels in the West Germanic languages greatly postdate any possible notion of a proto-language innovation (and cannot readily be regarded as "areal", either, because English and continental West Germanic were not a linguistic area). In a similar vein, there are many similar innovations in Germanic and Balto-Slavic that are far more likely areal features than traceable to a common proto-language, such as the uniform development of a high vowel (*u in the case of Germanic, *i/u in the case of Baltic and Slavic) before the PIE syllabic resonants *ṛ,* ḷ, *ṃ, *ṇ, unique to these two groups among IE languages, which is in agreement with the wave model. The Balkan sprachbund even features areal convergence among members of very different branches.

Using an extension to the Ringe-Warnow model of language evolution, early IE was confirmed to have featured limited contact between distinct lineages, whereas only the Germanic subfamily exhibited a less treelike behaviour as it acquired some characteristics from neighbours early in its evolution rather than from its direct ancestors. The internal diversification of especially West Germanic is cited to have been radically non-treelike.[23]

Proposed subgroupings[edit]

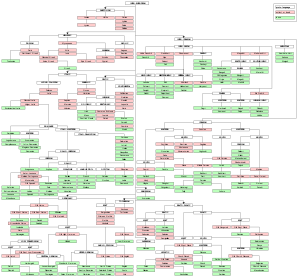

| Hypothetical Indo-European phylogenetic clades |

|---|

| Balkan |

| Other |

Specialists have postulated the existence of such subfamilies (subgroups) as Italo-Celtic, Graeco-Armenian, Graeco-Aryan, and Germanic with Balto-Slavic. The vogue for such subgroups waxes and wanes; Italo-Celtic for example was once a standard subgroup of Indo-European, but is now little honored, in part because much of the evidence it was based on was misinterpreted.[24]

Subgroupings of the Indo-European languages are commonly held to reflect genetic relationships and linguistic change. The generic differentiation of Proto-Indo-European into dialects and languages happened hand in hand with language contact and the spread of innovations over different territories.

Rather than being entirely genetic, the grouping of satem languages is commonly inferred as an innovative change that occurred just once, and subsequently spread over a large cohesive territory or PIE continuum that affected all but the peripheral areas.[25] Kortlandt proposes the ancestors of Balts and Slavs took part in satemization and were then drawn into the western Indo-European sphere.[26]

Shared features of Phrygian and Greek[27] and of Thracian and Armenian[28] group together with the Indo-Iranian family of Indo-European languages.[29] Some fundamental shared features, like the aorist (a verb form denoting action without reference to duration or completion) having the perfect active particle -s fixed to the stem, link this group closer to Anatolian languages[30] and Tocharian. Shared features with Balto-Slavic languages, on the other hand (especially present and preterit formations), might be due to later contacts.[31]

The Indo-Hittite hypothesis proposes the Indo-European language family to consist of two main branches: one represented by the Anatolian languages and another branch encompassing all other Indo-European languages. Features that separate Anatolian from all other branches of Indo-European (such as the gender or the verb system) have been interpreted alternately as archaic debris or as innovations due to prolonged isolation. Points proffered in favour of the Indo-Hittite hypothesis are the (non-universal) Indo-European agricultural terminology in Anatolia[32] and the preservation of laryngeals.[33] However, in general this hypothesis is considered to attribute too much weight to the Anatolian evidence. According to another view the Anatolian subgroup left the Indo-European parent language comparatively late, approximately at the same time as Indo-Iranian and later than the Greek or Armenian divisions. A third view, especially prevalent in the so-called French school of Indo-European studies, holds that extant similarities in non-satem languages in general - including Anatolian - might be due to their peripheral location in the Indo-European language area and early separation, rather than indicating a special ancestral relationship.[34] Hans J. Holm, based on lexical calculations, arrives at a picture roughly replicating the general scholarly opinion and refuting the Indo-Hittite hypothesis.[35]

Satem and centum languages[edit]

Main article: Centum–satem isogloss

The division of the Indo-European languages into a Satem vs. a Centum group was devised by Peter von Bradke in his 1890 work, "Concerning Method and Conclusions of Aryan (Indo-Germanic) Studies". In it, von Bradke described a division similar to that of Karl Brugmann's (1886), saying that the original "Aryans" knew two kinds of guttural sounds, the guttural or velar and palatal rows, each of which were aspirated and unaspirated. The velars were to be viewed as gutturals in a "narrow sense," and considered "pure K-sounds." Palatals were "often followed by labialization." This latter distinction led von Bradke to divide the palatal series into a group as a spirant and a pure K-sound, typified by the words satem and centum respectively.[36]

Suggested macrofamilies[edit]

See also: Origin of language

Some linguists propose that Indo-European languages form part of one of several hypothetical macrofamilies. However, these theories remain highly controversial, not being accepted by most linguists in the field. Some of smaller proposed macrofamilies are:

- Pontic, postulated by John Colarusso, which joins Indo-European with Northwest Caucasian.

- Indo-Uralic, joining Indo-European with Uralic.

Other, greater proposed families including Indo-European languages, are:

- Eurasiatic, a theory championed by Joseph Greenberg.

- Nostratic, comprising all or some of the Eurasiatic languages, as well as the Kartvelian, Uralic, Dravidian (or even the Elamo-Dravidian macrofamily), Altaic and Afroasiatic language families.

Objections to such groupings are not based on any theoretical claim about the likely historical existence or non-existence of such macrofamilies; it is entirely reasonable to suppose that they might have existed. The serious difficulty lies in identifying the details of actual relationships between language families; as it is very hard to find concrete evidence that transcends chance resemblance, or is not equally likely explained as being due to borrowing (including Wanderwörter, which can travel very long distances). Because the signal-to-noise ratio in historical linguistics declines steadily over time, at great enough time-depths it becomes open to reasonable doubt that it can even be possible to distinguish between signal and noise.

Evolution[edit]

Proto-Indo-European[edit]

Main article: Proto-Indo-European language

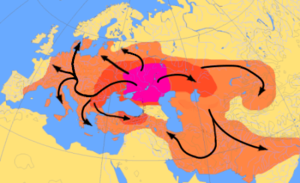

The proposed Proto-Indo-European language (PIE) is the hypothetical common ancestor of the Indo-European languages, spoken by the Proto-Indo-Europeans. From the 1960s, knowledge of Anatolian became certain enough to establish its relationship to PIE. Using the method of internal reconstruction an earlier stage, called Pre-Proto-Indo-European, has been proposed.

PIE was hypothetical inflected language, in which the grammatical relationships between words were signaled through inflectional morphemes (usually endings). The roots of PIE are basic morphemes carrying a lexical meaning. By addition of suffixes, they form stems, and by addition of desinences (usually endings), these form grammatically inflected words (nouns or verbs). The hypothetical Indo-European verb system is complex and, like the noun, exhibits a system of ablaut.

Diversification[edit]

See also: Indo-European migrations

The diversification of the parent language into the attested branches of daughter languages is historically unattested.The timeline of the evolution of the various daughter languages, on the other hand, is mostly undisputed, quite regardless of the question of Indo-European origins.

Using a mathematical analysis borrowed from evolutionary biology, Don Ringe and Wendy Tarnow propose the following evolutionary tree of Indo-European branches:[37]

- Pre-Anatolian (before 3500 BCE)

- Pre-Tocharian

- Pre-Italic and Pre-Celtic (before 2500 BCE)

- Pre-Armenian and Pre-Greek (after 2500 BCE)

- Pre-Germanic and Pre-Balto-Slavic;[37] proto-Germanic ca. 500 BCE[38]

- Proto-Indo-Iranian (2000 BCE)

David Anthony proposes the following sequence:[12]

- Pre-Anatolian (4200 BCE)

- Pre-Tocharian (3700 BCE)

- Pre-Germanic (3300 BCE)

- Pre-Italic and Pre-Celtic (3000 BCE)

- Pre-Armenian (2800 BCE)

- Pre-Balto-Slavic (2800 BCE)

- Pre-Greek (2500 BCE)

- Proto-Indo-Iranian (2200 BCE); split between Iranian and Old Indic 1800 BCE

From 1500 BCE the following sequence may be given:

- 1500 BC–1000 BC: The Nordic Bronze Age develops pre-Proto-Germanic, and the (pre)-Proto-Celtic Urnfield and Hallstatt cultures emerge in Central Europe, introducing the Iron Age. Migration of the Proto-Italic speakers into the Italian peninsula (Bagnolo stele). Redaction of the Rigveda and rise of the Vedic civilization in the Punjab. TheMycenaean civilization gives way to the Greek Dark Ages.

- 1000 BC–500 BC: The Celtic languages spread over Central and Western Europe. Baltic languages are spoken in a huge area from present-day Poland to the Ural Mountains.[39] Proto Germanic. Homer and the beginning of Classical Antiquity. The Vedic Civilization gives way to the Mahajanapadas. Siddhartha Gautama preachesBuddhism. Zoroaster composes the Gathas, rise of the Achaemenid Empire, replacing the Elamites and Babylonia. Separation of Proto-Italic into Osco-Umbrian and Latin-Faliscan. Genesis of the Greek and Old Italic alphabets. A variety of Paleo-Balkan languages are spoken in Southern Europe.

- 500 BC–1 BC/AD: Classical Antiquity: spread of Greek and Latin throughout the Mediterranean and, during the Hellenistic period (Indo-Greeks), to Central Asia and theHindukush. Kushan Empire, Mauryan Empire. Proto-Germanic. The Anatolian languages are extinct.

- 1 BC/AD 500: Late Antiquity, Gupta period; attestation of Armenian. Proto-Slavic. The Roman Empire and then the Migration period marginalize the Celtic languages to the British Isles.

- 500–1000: Early Middle Ages. The Viking Age forms an Old Norse koine spanning Scandinavia, the British Isles and Iceland. The Islamic conquest and the Turkic expansion results in the Arabization and Turkification of significant areas where Indo-European languages were spoken. Tocharian is extinct in the course of the Turkic expansion while Northeastern Iranian (Scytho-Sarmatian) is reduced to small refugia. Slavic languages spread over wide areas in central, eastern and southeastern Europe, largely replacing Romance in the Balkans (with the exception of Romanian) and whatever was left of the paleo-Balkan languages (with the exception of Albanian).

- 1000–1500: Late Middle Ages: Attestation of Albanian and Baltic.

- 1500–2000: Early Modern period to present: Colonialism results in the spread of Indo-European languages to every continent, most notably Romance (North, Central and South America, North and Sub-Saharan Africa, West Asia), West Germanic (English in North America, Sub-Saharan Africa, East Asia and Australia; to a lesser extent Dutch and German), and Russian to Central Asia and North Asia.

Important languages for reconstruction[edit]

In reconstructing the history of the Indo-European languages and the form of the Proto-Indo-European language, some languages have been of particular importance. These generally include the ancient Indo-European languages that are both well-attested and documented at an early date, although some languages from later periods are important if they are particularly linguistically conservative (most notably,Lithuanian). Early poetry is of special significance because of the rigid poetic meter normally employed, which makes it possible to reconstruct a number of features (e.g. vowel length) that were either unwritten or corrupted in the process of transmission down to the earliest extant written manuscripts.

Most important of all:

- Vedic Sanskrit (c. 1500 – 500 BC). This language is unique in that its source documents were all composed orally, and were passed down through oral tradition (shakha schools) for c. 2,000 years before ever being written down. The oldest documents are all in poetic form; oldest and most important of all is the Rig Veda (c. 1500 BC).

- Mycenaean Greek (c. 1450 BC)[40] and Ancient Greek (c. 750 – 400 BC). Mycenaean Greek is the oldest recorded form, but its value is lessened by the limited material, restricted subject matter, and highly ambiguous writing system. More important is Ancient Greek, documented extensively beginning with the two Homeric poems (the Iliad and the Odyssey, c. 750 BC).

- Hittite (c. 1700 – 1200 BC). This is the earliest-recorded of all Indo-European languages, and highly divergent from the others due to the early separation of the Anatolian languages from the remainder. It possesses some highly archaic features found only fragmentarily, if at all, in other languages. At the same time, however, it appears to have undergone a large number of early phonological and grammatical changes which, combined with the ambiguities of its writing system, hinder its usefulness somewhat.

Other primary sources:

- Latin, attested in a huge amount of poetic and prose material in the Classical period (c. 200 BC – 100 AD) and limited older material from as early as c. 600 BC.

- Gothic (the most archaic well-documented Germanic language, c. 350 AD), along with the combined witness of the other old Germanic languages: most importantly, Old English (c. 800 – 1000 AD), Old High German (c. 750 – 1000 AD) and Old Norse (c. 1100 – 1300 AD, with limited earlier sources dating all the way back to c. 200 AD).

- Old Avestan (c. 1700 – 1200 BC) and Younger Avestan (c. 900 BC). Documentation is sparse, but nonetheless quite important due to its highly archaic nature.

- Modern Lithuanian, with limited records in Old Lithuanian (c. 1500 – 1700 AD).

- Old Church Slavonic (c. 900 – 1000 AD).

Other secondary sources, of lesser value due to poor attestation:

- Luwian, Lycian, Lydian and other Anatolian languages (c. 1400 – 400 BC).

- Oscan, Umbrian and other Old Italic languages (c. 600 – 200 BC).

- Old Persian (c. 500 BC).

- Old Prussian (c. 1350 – 1600 AD); even more archaic than Lithuanian.

Other secondary sources, of lesser value due to extensive phonological changes and relatively limited attestation:

- Old Irish (c. 700 – 850 AD).

- Tocharian (c. 500 – 800 AD), underwent large phonetic shifts and mergers in the proto-language, and has an almost entirely reworked declension system.

- Classical Armenian (c. 400 – 500 AD).

- Albanian (c. 1450 – current time).

Sound changes[edit]

Main article: Indo-European sound laws

As the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) language broke up, its sound system diverged as well, changing according to various sound laws evidenced in the daughter languages.

PIE is normally reconstructed with a complex system of 15 stop consonants, including an unusual three-way phonation (voicing) distinction between voiceless, voiced and "voiced aspirated" (i.e. breathy voiced) stops, and a three-way distinction among velar consonants (k-type sounds) between "palatal" ḱ ǵ ǵh, "plain velar" k g gh and labiovelar kʷ gʷ gʷh. (The correctness of the terms palatal and plain velar is disputed; seeProto-Indo-European phonology.) All daughter languages have reduced the number of distinctions among these sounds, often in divergent ways.

As an example, in English, one of the Germanic languages, the following are some of the major changes that happened:

- As in other centum languages, the "plain velar" and "palatal" stops merged, reducing the number of stops from 15 to 12.

- As in the other Germanic languages, the Germanic sound shift changed the realization of all stop consonants, with each consonant shifting to a different one:

- bʰ → b → p → f

- dʰ → d → t → θ

- gʰ → g → k → x (Later initial x →h)

- gʷʰ → gʷ → kʷ → xʷ (Later initial xʷ →hʷ)

Each original consonant shifted one position to the right. For example, original dʰ became d, while original d became t and original t became θ (written th in English). This is the original source of the English sounds written f, th, h and wh. Examples, comparing English with Latin, where the sounds largely remain unshifted:- For PIE p: piscis vs. fish; pēs, pēdis vs. foot; pluvium "rain" vs. flow; pater vs. father

- For PIE t: trēs vs. three; māter vs. mother

- For PIE d: decem vs. ten; pēdis vs. foot; quid vs. what

- For PIE k: centum vs. hund(red); capere "to take" vs. have

- For PIE kʷ: quid vs. what; quandō vs. when

- Various further changes affected consonants in the middle or end of a word:

- The voiced stops resulting from the sound shift were softened to voiced fricatives (or perhaps the sound shift directly generated fricatives in these positions).

- Verner's law also turned some of the voiceless fricatives resulting from the sound shift into voiced fricatives or stops. This is why the t in Latin centum ends up as d in hund(red) rather than the expected th.

- Most remaining h sounds disappeared, while remaining f and th became voiced. For example, Latin decem ends up as ten with no h in the middle (but note taíhun "ten" in Gothic, an archaic Germanic language). Similarly, the words seven and have have a voiced v (compare Latin septem, capere), while father and mother have a voiced th, although not spelled differently (compare Latin pater, māter).

None of the daughter-language families (except possibly Anatolian, particularly Luvian) reflect the plain velar stops differently from the other two series, and there is even a certain amount of dispute whether this series existed at all in PIE. The major distinction between centum and satem languages corresponds to the outcome of the PIE plain velars:

- The "central" satem languages (Indo-Iranian, Balto-Slavic, Albanian and Armenian) reflect both "plain velar" and labiovelar stops as plain velars, often with secondary palatalization before a front vowel (e i ē ī). The "palatal" stops are palatalized and often appear as sibilants (usually but not always distinct from the secondarily palatalized stops).

- The "peripheral" centum languages (Germanic, Italic, Celtic, Greek, Anatolian and Tocharian) reflect both "palatal" and "plain velar" stops as plain velars, while the labiovelars continue unchanged, often with later reduction into plain labial or velar consonants.

The three-way PIE distinction between voiceless, voiced and voiced aspirated stops is considered extremely unusual from the perspective of linguistic typology — particularly in the existence of voiced aspirated stops without a corresponding series of voiceless aspirated stops. None of the various daughter-language families continue it unchanged, with numerous "solutions" to the apparently unstable PIE situation:

- The Indo-Aryan languages preserve the three series unchanged but have evolved a fourth series of voiceless aspirated consonants.

- The Iranian languages probably passed through the same stage, subsequently changing the aspirated stops into fricatives.

- Greek converted the voiced aspirates into voiceless aspirates.

- Italic probably passed through the same stage, but reflects the voiced aspirates as voiceless fricatives, especially f (or sometimes plain voiced stops in Latin).

- Celtic, Balto-Slavic, Anatolian and Albanian merge the voiced aspirated into plain voiced stops.

- Germanic and Armenian change all three series in a chain shift (e.g. with bh b p becoming b p f (known as Grimm's law in Germanic).

Among the other notable changes affecting consonants are:

- The Ruki sound law (s becomes /ʃ/ before r, u, k, i) in the satem languages.

- Loss of prevocalic p in Proto-Celtic.

- Development of prevocalic s to h in Proto-Greek, with later loss of h between vowels.

- Verner's law in Proto-Germanic.

- Grassmann's law (dissimilation of aspirates) independently in Proto-Greek and Proto-Indo-Iranian.

The following table shows the basic outcomes of PIE consonants in some of the most important daughter languages for the purposes of reconstruction. For a fuller table, see Indo-European sound laws.

| PIE | Skr. | O.C.S. | Lith. | Greek | Latin | Old Irish | Gothic | English | Examples | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PIE | Eng. | Skr. | Gk. | Lat. | Lith. etc. | |||||||||

| *p | p; phH | p | Ø; chT [x] | f; `-b- [β] | f; -v/f- | *pṓds ~ *ped- | foot | pád- | poús (podós) | pēs (pedis) | pãdas | |||

| *t | t; thH | t | t; -th- [θ] | þ [θ]; `-d- [ð]; tT- | th; `-d-; tT- | *tréyes | three | tráyas | treĩs | trēs | trỹs | |||

| *ḱ | ś [ɕ] | s | š [ʃ] | k | c [k] | c [k]; -ch- [x] | h; `-g- [ɣ] | h; -Ø-; `-y- | *ḱm̥tóm | hund(red) | śatám | he-katón | centum | šimtas |

| *k | k; cE [tʃ]; khH | k; čE [tʃ]; cE' [ts] | k | *kreuh₂ "raw meat" | OE hrēaw > raw | kravíṣ- | kréas | cruor | kraûjas | |||||

| *kʷ | p; tE; k(u) | qu [kʷ]; c(O) [k] | ƕ [ʍ]; `-gw/w- | wh; `-w- | *kʷid, kʷod | what | kím | tí | quid, quod | kàs | ||||

| *kʷekʷlom | wheel | cakrá- | kúklos | kãklas | ||||||||||

| *b | b; bhH | b | b [b]; -[β]- | p | ||||||||||

| *d | d; dhH | d | d [d]; -[ð]- | t | *déḱm̥(t) | ten, Goth. taíhun | dáśa | déka | decem | dẽšimt | ||||

| *ǵ | j [dʒ]; hH [ɦ] | z | ž [ʒ] | g | g [ɡ]; -[ɣ]- | k | c / k; chE' | *ǵénu, *ǵnéu- | OE cnēo > knee | jā́nu | gónu | genu | ||

| *g | g; jE [dʒ]; ghH; hH,E [ɦ] | g; žE [ʒ]; dzE' | g | *yugóm | yoke | yugám | zugón | iugum | jùngas | |||||

| *gʷ | b; de; g(u) | u [w > v]; gun- [ɡʷ] | b [b]; -[β]- | q [kʷ] | qu | *gʷīw- | quick "alive" | jīvá- | bíos, bíotos | vīvus | gývas | |||

| *bʰ | bh; b..Ch | b | ph; p..Ch | f-; b | b [b]; -[β]-; -f | b; -v/f-(rl) | *bʰerō | bear "carry" | bhar- | phérō | ferō | OCS berǫ | ||

| *dʰ | dh; d..Ch | d | th; t..Ch | f-; d; b(r),l,u- | d [d]; -[ð]- | d [d]; -[ð]-; -þ | d | *dʰwer-, dʰur- | door | dhvā́raḥ | thurā́ | forēs | dùrys | |

| *ǵʰ | h [ɦ]; j..Ch | z | ž [ʒ] | kh; k..Ch | h; h/gR | g [ɡ]; -[ɣ]- | g; -g- [ɣ]; -g [x] | g; -y/w-(rl) | *ǵʰans- | goose, OHG gans | haṁsáḥ | khḗn | (h)ānser | žąsìs |

| *gʰ | gh; hE [ɦ]; g..Ch; jE..Ch | g; žE [ʒ]; dzE' | g | |||||||||||

| *gʷʰ | ph; thE; kh(u); p..Ch; tE..Ch; k(u)..Ch | f-; g / -u- [w]; ngu [ɡʷ] | g; b-; -w-; ngw | g; b-; -w- | *sneigʷʰ- | snow | sneha- | nípha | nivis | sniẽgas | ||||

| *gʷʰerm- | ??warm | gharmáḥ | thermós | formus | Latv. gar̂me | |||||||||

| *s | s | h-; -s; s(T); -Ø-; [¯](R) | s; -r- | s [s]; -[h]- | s; `-z- | s; `-r- | *septḿ̥ | seven | saptá | heptá | septem | septynì | ||

| ṣruki- [ʂ] | xruki- [x] | šruki- [ʃ] | *h₂eusōs "dawn" | east | uṣā́ḥ | āṓs | aurōra | aušra | ||||||

| *m | m | m [m]; -[w̃]- | m | *mūs | mouse | mū́ṣ- | mũs | mūs | OCS myšĭ | |||||

| *-m | -m | -˛ [˜] | -n | -m | -n | -Ø | *ḱm̥tóm | hund(red) | śatám | (he)katón | centum | OPrus simtan | ||

| *n | n | n; -˛ [˜] | n | *nokʷt- | night | nákt- | núkt- | noct- | naktis | |||||

| *l | r (dial. l) | l | *leuk- | light | rócate | leukós | lūx | laũkas | ||||||

| *r | r | *h₁reudʰ- | red | rudhirá- | eruthrós | ruber | raũdas | |||||||

| *i̯ | y [j] | j [j] | z [zd > dz > z] / h; -Ø- | i [j]; -Ø- | Ø | j | y | *yugóm | yoke | yugám | zugón | iugum | jùngas | |

| *u̯ | v [ʋ] | v | v [ʋ] | w > h / Ø | u [w > v] | f; -Ø- | w | *h₂weh₁n̥to- | wind | vā́taḥ | áenta | ventus | vėtra | |

| PIE | Skr. | O.C.S. | Lith. | Greek | Latin | Old Irish | Gothic | English | ||||||

- Notes:

- C- At the beginning of a word.

- -C- Between vowels.

- -C At the end of a word.

- `-C- Following an unstressed vowel (Verner's law).

No comments:

Post a Comment