Society of the Cincinnati

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| |

| Motto | Omnia reliquit servare rempublicam[1] |

|---|---|

| Formation | May 13, 1783 |

| Purpose | Patriotism, Universal Rights, Franco-American friendship |

| Headquarters | Anderson House, Washington D.C. |

Membership

| private hereditary |

President General

| Ross Gamble Perry |

| Website | societyofthecincinnati |

The Society of the Cincinnati is a historical, hereditary lineage organization with branches in the United States and France, founded in 1783 to preserve the ideals and fellowship of the officers of the Continental Armywho served in the American Revolutionary War. The city of Cincinnati, Ohio, then a small village, shares its name with the Society. Now in its third century, the Society promotes public interest in the American Revolution through its library and museum collections, exhibitions, programs, publications, and other activities. It is the oldest lineage society in North America.

Contents

[hide]Origins[edit]

| This section includes a list of references, but its sources remain unclear because it has insufficient inline citations. (June 2010) |

The concept of the Society of the Cincinnati was that of Major General Henry Knox. The first meeting of the Society was held in May 1783 at a dinner at Mount Gulian (Verplanck House) in Fishkill, New York, before the Britishevacuation from New York City. The meeting was chaired by Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Hamilton, and the participants agreed to stay in contact with each other after the war. Membership was generally limited to officers who had served at least three years in the Continental Army or Navy; it included officers of the French Army and Navy above certain ranks. Officers in the Continental Line who died during the War were also entitled to be recorded as members, and membership would devolve to their eldest male heir. Members of the considerably larger fighting forces comprising the Colonial Militias and Minutemen were not entitled to join the Society.

Later in the 18th century, the Society's rules adopted a system of primogeniture wherein membership was passed down to the eldest son after the death of the original member. Present-day hereditary members generally must be descended from an officer who served in the Continental Army or Navy for at least three years, from an officer who died or was killed in service, or from an officer serving at the close of the Revolution. Each officer may be represented by only one descendant at any given time, following the rules ofprimogeniture. (The rules of eligibility and admission are controlled by each of the 14 Constituent Societies to which members are admitted. They differ slightly in each society, and some allow more than one descendant of an eligible officer.)(The requirement for primogeniture made the society controversial in its early years, as the new states quickly did away with laws supporting primogeniture and others associated with the English feudal system.)

The Society is named after Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus, who left his farm to accept a term as Roman Consul and served as Magister Populi (with temporary powers similar to that of a modern-era dictator). He assumed lawful dictatorial control of Rome to meet a war emergency. When the battle was won, he returned power to the Senate and went back to plowing his fields. The Society's motto reflects that ethic of selfless service: Omnia reliquit servare rempublicam ("He relinquished everything to save the Republic").[1] The Society has had three goals: "To preserve the rights so dearly won; to promote the continuing union of the states; and to assist members in need, their widows, and their orphans."

Within 12 months of the founding, a constituent Society had been organized in each of the 13 states and in France. Of about 5,500 men originally eligible for membership, 2,150 had joined within a year. King Louis XVI ordained the French Society of the Cincinnati, which was organized on July 4, 1784 (Independence Day). Up to that time, the King of France had not allowed his officers to wear any foreign decorations, but he made an exception in favor of the badge of the Cincinnati.

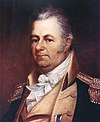

George Washington was elected the first President General of the Society. He served from December 1783 until his death in 1799. The second President General was Alexander Hamilton. Upon Hamilton's death due to his duel with Aaron Burr, the third President General of the Society was Charles Cotesworth Pinckney. In 1808, he ran unsuccessfully for President of the United States against James Madison.

Its members have included notable military and political leaders, including 23 signers of the United States Constitution.

Founding members[edit]

Connecticut[edit]

Abraham Baldwin, Joel Barlow, Zebulon Butler, John Chester, David Humphreys, Jedediah Huntington, Jacob Kingsbury, Jonathan Trumbull, Jr.

Delaware[edit]

Daniel Jenifer Adams, Enoch Anderson, Joseph Anderson, Thomas Anderson, William Anderson, Caleb Prew Bennett, James Campbell, John Driskill, Henry Duff, Reuben Gilder, David Hall, Joseph Hossman, John Vance Hyatt, Peter Jacquett, Jr., James Jones, Charles Kidd, David Kirkpatrick, Robert Henry Kirkwood, Henry Latimer, John Learmonth, William McKennan, Allen (Allan) McLane, Stephen McWilliam, Nathaniel Mitchell, George Monro, James Moore, John Patten, John Platt, Charles Pope, George Purvis, Edward Roche, Ebenezer Augustus Smith, James Tilton, Nathaniel Twinning, Joseph Vaughan, William Adams (son of Nathan Adams), and Joseph Haslet (son of John Haslet).

France[edit]

Jean Baptiste de Traversay, Maxime Julien Émeriau de Beauverger, Pierre L'Enfant, Louis-René Levassor de Latouche Tréville, Paul François Ignace de Barlatier de Mas, Gilbert du Motier, Louis Marc Antoine de Noailles, Georges René Le Peley de Pléville, Charles Armand Tuffin, Jean Gaspard Vence, Alexandre-Théodore-Victor, Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, Joseph de Cambis

Georgia[edit]

Maryland[edit]

Lloyd Beall, Josias Carvel Hall, Mordecai Gist, John Gunby, Thomas Lancaster Lansdale,[3] James Lingan, Daniel Morgan, Nathaniel Ramsey, William Smallwood, Tench Tilghman, Otho Williams

Massachusetts[edit]

Jeduthun Baldwin, John Brooks, Henry Burbeck, David Cobb(Colonel), John Crane, Thomas Henry Cushing, Henry Dearborn, William Eustis, Constant Freeman, John Greaton, Africa Hamlin, William Heath, William Hull, Thomas Hunt, Henry Knox, Henry Jackson, Michael Jackson, Simon Larned, Benjamin Lincoln, Samuel Nicholson, William North, Rufus Putnam,William Shepard, William Stacy, Benjamin Tupper, Elisha Horton, Abraham Williams

New Hampshire[edit]

New Jersey[edit]

Abraham Appleton, Jeremiah Ballard, William Barton, John Beatty (Continental Congress), John Bishop, John Blair, Joseph Bloomfield, Absalom Bonham, James Bonnell, Seth Bowen, Nathaniel Bowman, David Brearley, Joseph Buck, Eden Burrowes, John Burrowes, Lambert Cadwalader, Samuel Conn, John Conway, Richard Cox, John Noble Cumming, Ephraim Darby, Elias Dayton, Jonathan Dayton, Cyrus De Hart, Nathaniel Donnell, John Doughty, Lewis Ford Dunham, Ebenezer Elmer, Peter Faulkner, Chilion Ford, Mahlon Ford, David Forman, Jonathan Forman, Luther Halsey, Jacob Harris, James Heard, John Heard, William Helms, Samuel Hendry, John Holmes, Jonathan Holmes, Richard Howell, Andrew Hunter, Jacob Hyer, William Kersey, Derick Lane, Richard Lloyd, Francis Luce, Absalom Martin, William Malcolm, Aaron Ogden, Matthias Ogden, Benajah Osmun, John Peck, Robert Pemberton, William Sanford Pennington, Jonathan Phillips, Jacob Piatt, William Piatt, Samuel Reading, John Reed, John Reed, John Beucastle, Jonathan Rhea, John Ross, Cornelius Riker Sedam, Samuel C. Seeley, Israel Shreve, Samuel Moore Shute, William Shute, Jonathan Snowden, Oliver Spencer, Moses Sprowl, Abraham Stout, Wessel Ten Broeck Stout, Edmund Disney Thomas, William Tuttle, George Walker, Abel Weymen, and Ephraim Lockhart Whitlock.

New York[edit]

Aaron Burr, George Clinton, James Clinton, John Doughty, Nicholas Fish, Peter Gansevoort, Alexander Hamilton, Rufus King, Joseph Hardy, John Lamb (general), Morgan Lewis, Henry Beekman Livingston, Alexander McDougall, Charles McKnight, David Olyphant, Philip Schuyler, John Morin Scott, William Stephens Smith, John Stagg Jr, Ebenezer Stevens,[4] Silas Talbot, Benjamin Tallmadge, Philip Van Courtlandt, Richard Varick, William Scudder, Dr. Caleb Sweet,[5] Maj.Gen.Baron von Steuben.Lt.Col., Bernardus Swartwout, Cornelius Swartwout,[6] (Baron) Frederick Von Weisenfels

North Carolina[edit]

William Lee Alexander, James Armstrong, John Armstrong, Thomas Armstrong, John Baptist Ashe, Samuel Ashe, Jr., Peter Bacot, Benjamin Bailey, Kedar Ballard, Robert Bell, Jacob Blount, Reading Blount, Adam Boyd, Joseph Blyth(e), Gee Bradley, Alexander Brevard, Joseph Brevard, William Bush, Thomas Callender, John Campbell, James Campen, Benjamin Carter, Thomas Clark, John Clendennen, Benjamin Coleman, John Craddock, Anthony Crutcher, John Daves, Samuel Denny, Charles Dixon, Tilghman Dixon, Wynn Dixon, George Doherty, Thomas Donoho, Thomas Evans, Richard Fenner, Robert Fenner, William Ferebee, Thomas Finney, John Ford (Foard), James Furgus (Fergus), Charles Gerrard (Garrard), Francis Graves, James West Green, Joshua Hadley, Clement Hall, Selby Harney, Robert Hays, John Hill, Thomas Hogg, Hardy Holmes, Robert Howe, John Ingles, Curtis Ivey, Abner Lamb, Nathaniel Lawrence, Nehemiah Long, Archibald Lytle, William Lytle, William Maclean (McLane), William McClure, James McDougall, John McNees, Griffith John McRee, Joseph Monfort, James Moore, Henry Murfree, John Nelson, Thomas Pasture (Pasteur), William Polk, Robert Raiford, Jesse Read, John Read (Reed), Joseph Thomas Rhodes, William Sanders (Saunders), Anthony Sharp(e), Daniel Shaw, Stephen Slade, John Slaughter, Jesse Steed, John Summers, Jethro Sumner, James Tate, Howell Tatum, James Tatum, James Thackston, Nathaniel Williams, William Williams, and Edward Yarborough.

Pennsylvania[edit]

John Armstrong, Jr., Joshua Barney, John Barry, William Bingham, Thomas Boude, Daniel Brodhead, David Brooks, Edward Butler, Richard Butler, Thomas Butler, William Butler, Thomas Craig, Richard Dale, Edward Hand, Josiah Harmar,Thomas Hartley, William Irvine, Francis Johnston, John Paul Jones, Robert Magaw, Thomas Mifflin, John Peter Gabriel Muhlenberg, Alexander Murray, Lewis Nicola, Samuel Nicholas, Zebulon Pike, Thomas Proctor, Arthur St. Clair, William Thompson, Anthony Wayne, Baron von Steuben

Rhode Island[edit]

William Barton, Archibald Crary, Nathanael Greene, Moses Hazen, Daniel Jackson, William Jones, David Lyman, Coggeshall Olney, Jeremiah Olney, Stephen Olney, William Tew, Simeon Thayer, James Mitchell Varnum, Abraham Whipple

South Carolina[edit]

Isaac Huger, William Jackson, Francis Marion, Lewis Morris, William Moultrie, Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, Thomas Pinckney, Andrew Pickens, James F. Byrnes (honorary)

Sweden[edit]

Count Axel von Fersen, Baron Curt von Stedingk

Virginia[edit]

George Baylor, Francis T. Brooke, Abraham Buford, Nicholas Cabell,William Overton Callis, Edward Carrington, Louis de Corny, John Cropper, William Davies, Christian Febiger, Horatio Gates, John Gibson, William Grayson, John Green,Charles Harrison, William Heth,Peter Higgins. Samuel Hopkins, Henry Lee III, John Crittenden, Sr., Charles Lewis, George Matthews, James Monroe, Daniel Morgan, John Muhlenberg, John Neville, Thomas Overton, Thomas Posey, Major John Pryor, William Russell, Richard Taylor, John Ward, John Watts, George Washington, George Augustine Washington, George Weedon, David Williams, Willis Wilson, James Wood.

Insignia[edit]

On June 19, 1783, the General Society of the Cincinnati adopted the bald eagle as its insigne. It is one of America's first post-revolution symbols and an important piece of American iconography. It is the second official emblem to represent America as the bald eagle, following the Great Seal of the United States. It was likely derived from the same discourse that produced the seal.

The suggestion of the bald eagle as the Cincinnati insignia was made by Major Pierre L'Enfant, a French officer who joined the American Army in 1777, served in the Corps of Engineers and later become a member of the Society. He noted, "The Bald Eagle, which is unique to this continent, and is distinguished from those of other climates by its white head and tail, appears to me to deserve attention."[7] In 1783, L'Enfant was commissioned to travel to France to have the first Eagle badges made, based on his design. (L'Enfant later planned and partially laid out the city of Washington, D.C.)

The medallions at the center of the Cincinnati American Eagle depict, on the obverse, Cincinnatus receiving his sword from the Roman Senators and, on the reverse, Cincinnatus at his plow being crowned by the figure of Pheme (personificationof fame). The Society's colors, light blue and white, symbolize the fraternal bond between the United States and France.

A specially commissioned "Eagle" worn by President General George Washington was presented to Lafayette in 1824 during his grand tour of the United States. This medallion had remained in possession of the Lafayette family,[8] until sold at auction on December 11, 2007, for 5.3 million USD by Lafayette's great-great granddaughter. It was purchased by the Josée and René de Chambrun Foundation and will be displayed at Chateau La Grange, Lafayette's home 30 miles east ofParis. The medal, believed to have its original ribbon and red leather box, will be displayed in Lafayette's bedroom. It also might be displayed at Mount Vernon, Washington's former home in Virginia.[9] This was one of three eagles known to have been owned by Washington. Washington most commonly wore the "diamond eagle," a diamond-encrusted design that was given to him by the French matelots (sailors). This diamond eagle continues to be passed down to each President General of the Society of the Cincinnati as part of his induction into office.

The Cincinnati Eagle is displayed in various places of public importance, including the city center of Cincinnati, Ohio (named for the Society) at Fountain Square, alongside the U.S. flag and the city flag. The flag of the Society displays blue and white stripes and a dark blue canton (containing a circle of 14 stars around the Cincinnati Eagle to designate the thirteen colonies and France) in the upper corner next to the hoist. Refer to the section below on "The Later Society" for the city's historical connection to the Cincinnati.

During ceremonial occasions badges of society members may be worn on military and naval uniforms.[10]

Criticism[edit]

When news of the foundation of the society spread, judge Aedanus Burke published several pamphlets under the pseudonym Cassius where he criticized the society as an attempt at reestablishing an hereditary nobility in the new republic.[11]The pamphlets, entitled An Address to the Freemen of South Carolina (January 1783) and Considerations on the Society or Order of Cincinnati (October 1783) sparked a general debate that included prominent names, including Thomas Jefferson[12] and John Adams.[13] The criticism voiced concern about the apparent creation of an hereditary elite; membership eligibility is inherited through primogeniture, and generally excluded enlisted men and militia officers, unless they were placed under "State Line" or "Continental Line" forces for a substantial time period, and their descendants. Benjamin Franklin was among the Society's earliest critics. He was concerned about the creation of a quasi-noble order, and of the Society's use of the eagle in its emblem, as evoking the traditions of heraldry and the English aristocracy. In a letter to his daughter Sarah Bache written on January 26, 1784, Franklin commented on the ramifications of the Cincinnati:

However, Franklin's opinion changed after the country stabilized and he joined the Pennsylvania Society as an honorary member.[citation needed]

The influence of the Cincinnati members, former officers, was another concern. When delegates to the Constitutional Convention were debating the method of choosing a president, James Madison (the secretary of the Convention) reported the following speech of Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts:

The debate spread to France on account of the eligibility of French veterans from the Revolutionary War. In 1785 Honoré Gabriel Riqueti, comte de Mirabeau was approached by Franklin, who was at the time stationed in Paris and suggested to him to write something about the society directed at the French public.[16] Mirabeau was provided with Burke's pamphlets and Franklin's letter to his daughter, and from this, with the help of Nicolas Chamfort, created his own enlarged version entitled Considérations sur l'Ordre de Cincinnatus which was published in London November that year, an English translation carried out by Samuel Romilly followed, of which an American edition was published in 1786.[17]

Following this public debate and criticism, George Washington, who had been unaware of the particulars of the charter when he agreed to become president of the society, began to have doubts about the benefit of the society. He had in fact considered abolishing the society on its very first general meeting 4 May 1784.[18] However in the mean time Major L'Enfant had arrived bringing his designs of the diplomas and medals, as well as news of the success of the society in France, which made an abolishment of the society impossible. Washington instead at the meeting launched an ultimatum, that if the clauses about heredity were not abandoned, he would resign from his post as president of the society. This was accepted, and furthermore informal agreement was made not to wear the eagles in public, so as not to resemble European chivalrous orders. A new charter, the so-called Institution, was printed, which omitted among others the disputed clauses about heredity. This was sent to the local chapters for approval, and it was approved in all of them except for the chapters in New York, New Hampshire and Delaware. However when the public furore about the society had died down, the new Institution was rescinded, and the original reintroduced, including the clauses about heredity.[19]

The French chapter, who had obtained official permission to form from the king Louis XVI of France, also abolished heredity, but never reintroduced it, and thus the last members was approved 3 February 1792, shortly before the French monarchy was disbanded.[20]

Later activities[edit]

The members of the Cincinnati were among those developing many of America's first and largest cities to the west of the Appalachians, most notably Cincinnati, Ohio and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The first governor of the Northwest Territory, Arthur St. Clair, was a member of the Society. He renamed a small settlement "Cincinnati" to honor the Society and to encourage settlement by Society members. Among them were Captain Jacob Piatt, who settled across the river from Cincinnati in northern Kentucky on land granted to him for his service during the War. Captain David Ziegler was the first Mayor of Cincinnati. Richard Varick was a Mayor of New York City. Lt. Ebenezer Denny (1761–1822), an original Pennsylvanian Cincinnatus, was elected the first mayor of the incorporated city of Pittsburgh in 1816. Pittsburgh developed from Fort Pitt, which had been commanded since 1777-1783 by four men who were founding members of the Society.

Today's Society supports efforts to increase public awareness and memory of the ideals and actions of the men who created the American Revolution and an understanding of American history, with an emphasis on the period from the outset of the Revolution to the War of 1812. At its headquarters at Anderson House in Washington, DC, the Society holds manuscript, portrait, and model collections pertaining to events of and military science during this period.[21] Members of the Society have contributed to endow professorships, lecture series, awards, and educational materials in relation to the United States' representative democracy.[22] The definition and acceptance of membership has remained with the constituent societies rather than with the General Society in Washington.

Over the years, membership rules have continued as first established. They provide for approving the application of a collateral heir if the direct male line dies out. Membership has been expanded in some state societies to include descendants of those who died during the war, but it remains limited.

An officer of the Continental army during the Revolutionary War can generally be represented in the Society of The Cincinnati by only one descendant at a time. The only U.S. President who was a true hereditary member was Franklin Pierce. The General Society no longer admits honorary members. Andrew Jackson and Zachary Taylor were honorary members before becoming presidents. Other presidents became honorary members while in office, and after leaving office. Each of the fourteen constituent societies has honorary members, but these men cannot designate an heir (referred to as a successor member).

The Society maintains a tradition of service in American government, especially in the federal executive branch. Members of the society have served in the Armed Forces, the State Department and other parts of the executive branch.

Anderson House, National Headquarters[edit]

Main article: Larz Anderson House

Anderson House, also known as Larz Anderson House, located at 2118 Massachusetts Avenue, NW in the Dupont Circle neighborhood of Washington, D.C., houses the Society's national headquarters, historic house museum, and research library. It is located on the Embassy Row section, near international embassies.

Anderson House was built between 1902 and 1905 as the winter residence of Larz Anderson, an American diplomat, and his wife, Isabel Weld Perkins, an author and American Red Cross volunteer. The architects Arthur Little and Herbert Browne of Boston designed Anderson House in the Beaux-Arts style. Anderson House was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1971 and was further designated a National Historic Landmark in 1996.[23][24]

Today, Anderson House serves its members and the public as a headquarters, museum, and library. The Society's museum collections include portraits, armaments, and personal artifacts of Revolutionary War soldiers; commemorative objects; objects associated with the history of the Society and its members, including Society of the Cincinnati china and insignia; portraits and personal artifacts of members of the Anderson family; and artifacts related to the history of the house, including the U.S. Navy's occupation of it during World War II.

Library[edit]

The library of the Society of the Cincinnati collects, preserves, and makes available for research printed and manuscript materials relating to the military and naval history of the eighteenth century and early nineteenth century, with a particular concentration on the people and events of the American Revolution and the War of 1812. The collection includes a variety of modern and rare materials including official military documents, contemporary accounts and discourses, manuscripts, maps, graphic arts, literature, and many works on naval art and science. In addition, the library is the home to the archives of the Society of the Cincinnati as well as a collection of material relating to Larz and Isabel Anderson. The library is open to researchers by appointment.

Museum in Exeter, New Hampshire[edit]

The Society of the Cincinnati in the State of New Hampshire owns and operates through a board of governors the American Independence Museum in Exeter, New Hampshire. The American Independence Museum is a private, not-for-profit institution whose mission is to provide a place for the study, research, education and interpretation of the American Revolution and of the role that New Hampshire, Exeter, and the Gilman family played in the founding of the new republic. Museum collections include two rare drafts of the U.S. Constitution, an original Dunlap Broadside of the United States Declaration of Independence, as well as an original Badge of Military Merit, awarded by George Washington to soldiers demonstrating extraordinary bravery. Exhibits highlight the Society of the Cincinnati, the nation’s oldest veterans’ society, and its first president, George Washington. Permanent collections include American furnishings, ceramics, silver, textiles and military ephemera. See below for a link to the museum.

Affiliations[edit]

- American Philosophical Society: many Cincinnati were among its first board members and contributors; modern societies maintain informal, collegial relationships only

Representation in other media[edit]

Anderson House has been featured on the A&E television series, America's Castles, as well as C-SPAN.

List of noteworthy members[edit]

Original members[edit]

- Chaplain and United States Senator Abraham Baldwin

- Chaplain and Minister to France Joel Barlow

- Captain Joshua Barney, USN

- Commodore John Barry, USN

- Colonel William Barton

- U.S. Representative Thomas Boude

- Delegate to the U.S. Constitutional Convention David Brearly

- Surgeon's Mate Isaac Bronson

- Lieutenant and U.S. Representative David Brooks

- Major General and Governor John Brooks

- Lieutenant Colonel, Senator and Vice President Aaron Burr

- Captain David Bushnell

- Major General Richard Butler

- Lieutenant Colonel and Congressman Edward Carrington

- Brigadier General, Governor and Vice President George Clinton

- Brevet Major General James Clinton

- Captain Richard Dale, USN

- Captain Luke Day

- Major General and Secretary of War Henry Dearborn

- Congressman Ebenezer Denny

- Lieutenant General the Comte de Rochambeau

- Lieutenant Colonel John Doughty

- Surgeon and Secretary of War William Eustis

- Colonel Christian Febiger

- Major Nicholas Fish

- Major Robert Forsyth

- Brigadier General Peter Gansevoort

- Major General Horatio Gates

- Captain Nicholas Gilman

- Major General Nathanael Greene

- Major General Alexander Hamilton (President General)

- Brevet Brigadier General Josiah Harmar

- Major General Robert Howe

- Brigadier General Isaac Huger

- Major David Humphreys

- Brigadier General Andrew Pickens

- Major General Henry Jackson

- Brevet Brigadier General Michael Jackson

- Major William Jackson

- Captain John Paul Jones, USN

- Captain William Jones, USMC

- Brigadier General Tadeusz Kościuszko

- Major General Henry Knox (Secretary General)

- Major General the Marquis de La Fayette

- Major General Henry Lee III ("Light Horse Harry")

- Major Pierre L'Enfant

- Major General and Governor Morgan Lewis (President General)

- Major General Benjamin Lincoln

- Captain James Lingan

- Brevet Brigadier General and Governor George Mathews

- Major and US Marshal Allen McLane

- Surgeon Charles McKnight

- Brigadier General Lachlan McIntosh

- Lieutenant Colonel James Monroe (President of the United States.)

- Brigadier General Daniel Morgan

- Major Samuel Nicholas, USMC

- Captain John Nicholson, USN

- Captain Samuel Nicholson, USN

- Brigadier General and Senator William North

- Major, Governor and Senator Aaron Ogden (President General)

- Major General Charles C. Pinckney (President General)

- Major General Thomas Pinckney (President General)

- Brevet Major William Popham (Last original member to become President General.)

- Major General, Senator and Governor Thomas Posey

- Brigadier General Rufus Putnam

- Lieutenant Colonel Nathaniel Ramsey

- Major General and Senator Philip Schuyler

- Major General and Congressman William Shepard

- Major General William Smallwood

- Lieutenant Colonel William Stephens Smith

- Major General Arthur St. Clair

- Lieutenant Colonel William Stacy

- Major General John Sullivan

- Captain Silas Talbot, USN

- Brevet Lieutenant Colonel and Congressman Benjamin Tallmadge

- Lieutenant Colonel Richard Taylor - Father of President Zachary Taylor.

- Lieutenant Colonel Tench Tilghman

- Lieutenant Colonel Jonathan Trumbull, Jr. - Aide to General Washington and Governor of Connecticut.

- Brigadier General James Mitchell Varnum

- Colonel Axel von Fersen the Younger

- Lieutenant Colonel Curt von Stedingk (French Army.)

- Major General Baron Von Steuben

- General George Washington - President of the United States and President General of the Society.

- Major General Anthony Wayne

- Captain Abraham Whipple, USN

- Brigadier General Otho Holland Williams

- Major David Ziegler

Hereditary members[edit]

[edit]

- General John K. Waters - Career Army officer.

- Admiral Hilary P. Jones - Commander of the United States Battle Fleet.

- Admiral John S. McCain, Sr. - Admiral during World War II and grandfather of U.S. Senator John McCain.

- Admiral John S. McCain, Jr. - Commander of United States Pacific Command during the Vietnam War, and father of U.S. Senator John McCain. The two McCains are the only father-and-son four-star admirals in U.S. Navy history.

- Lieutenant General Allen M. Burdette, Jr. - Army aviator and Vietnam war veteran.

- Lieutenant General Ridgely Gaither - Career Army officer.

- Lieutenant General, Governor and Senator Wade Hampton III

- Major General Silas Casey - Civil War general.

- Major General Henry A. S. Dearborn - President General of the Society and congressman.

- Major General William B. Franklin - Veteran of the Mexican War and the Civil War.

- Major General Edgar Erskine Hume - President General of the Society.

- Major General Edwin Vose Sumner, Jr. - Civil War and Spanish–American War veteran.

- Rear Admiral Charles Henry Davis

- Rear Admiral Henry Thatcher - Grandson of Major General Henry Knox and Civil War veteran.

- Brevet Major General Nicholas Longworth Anderson

- Brevet Major General Henry Jackson Hunt - Union general in the Civil War.

- Brigadier General William Bancroft - Mayor of Cambridge, Massachusetts and general during the Spanish–American War.

- Brigadier General Thomas Lincoln Casey - Army engineer who oversaw completion of the Washington Monument.

- Brigadier General Thomas L. Crittenden - Civil War general.

- Brigadier General and President Franklin Pierce (Only president of the United States to be a hereditary member.)

- Brigadier General Cornelius Vanderbilt III - World War I veteran.

- Brevet Brigadier General Hazard Stevens - Medal of Honor recipient.

- Lieutenant Colonel Frederick Lippitt - Philanthropist.

- Major Archibald Butt - Presidential military aide who died on the Titanic.

- Major Asa Bird Gardiner - Secretary General of the Society.

- Major Cornelius Vanderbilt IV - Newspaper editor.

Government officials[edit]

- President Franklin Pierce

- Rt. Hon. Sir Winston Churchill KG, CH, FRS - Hereditary member of the Connecticut society; his great-grandson, Duncan Sandys, is currently a member.

- Secretary of State, Senator and Governor Hamilton Fish - Long-time President General of the Society.

- Secretary of War Newton D. Baker

- Supreme Court Associate Justice Stanley Forman Reed

- Governor and United States Senator William Bulkeley - Governor of Connecticut and president of Aetna Insurance Company.

- Governor Wilbur L. Cross

- Governor William W. Hoppin - Governor of Rhode Island.

- Governor Charles Warren Lippitt - Governor of Rhode Island.

- Governor LeBaron Bradford Prince - Governor of New Mexico Territory.

- Governor Thomas Stockton - Governor of Deleware.

- Governor and Senator George Peabody Wetmore

- Ambassador Larz Anderson - Socialite and diplomat.

- Ambassador Robert W. Bingham

- Minister Nicholas Fish II - Minister to Belgium.

- Senator Warren R. Austin

- Senator Chauncey Depew - Founder of the Pilgrims Society.

- Senator Charles Mathias - United States senator from Maryland.

- Senator Claiborne Pell - Long serving senator from Rhode Island.

- Senator Hugh Doggett Scott, Jr. - Congressman and United States senator from Pennsylvania.

- Senator Charles Sumner - Abolitionist senator from Massachusetts.

- Congressman Horace Binney

- Congressman Hamilton Fish II

- Chief Justice of the South Carolina Supreme Court Milledge Lipscomb Bonham

Others[edit]

- Mr. Henry L. P. Beckwith - Heraldist, historian and genealogist (Currently living and self-listed).

- Mr. John Nicholas Brown I - Book collector and philanthropist.

- The Honorable John Nicholas Brown - Philanthropist.

- Astronomer Benjamin Apthorp Gould

- Reverend Alexander Hamilton - great-grandson of Alexander Hamilton

No comments:

Post a Comment