Return to Spain[edit]

De Soto returned to Spain with an enormous share of the Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire. He was admitted into the prestigious Order of Santiago. His share was awarded to him by the King of Spain, and he received 724 marks of gold, 17,740 pesos.[9] He married Isabel de Bobadilla, daughter of Pedrarias Dávila and a relative of a confidante of Queen Isabella.

De Soto petitioned King Charles for the government of Guatemala with "permission to make discovery in the South Sea," but was granted the governorship of Cuba instead. De Soto was expected to colonize the North American continent for Spain within four years, for which his family would be given a sizable piece of land.

Fascinated by the stories of Cabeza de Vaca, who had survived in North America after becoming a castaway and just returned to Spain, de Soto selected 620 eager Spanish and Portuguese volunteers, including some of African descent, for the governing of Cuba and conquest of North America. Averaging 24 years of age, the men embarked from Havana on seven of the King's ships and two caravels of de Soto's. With tons of heavy armour and equipment, they also carried more than 500 livestock, including 237 horses and 200 pigs, for their planned four-year continental expedition.

De Soto's exploration of North America[edit]

Historiography[edit]

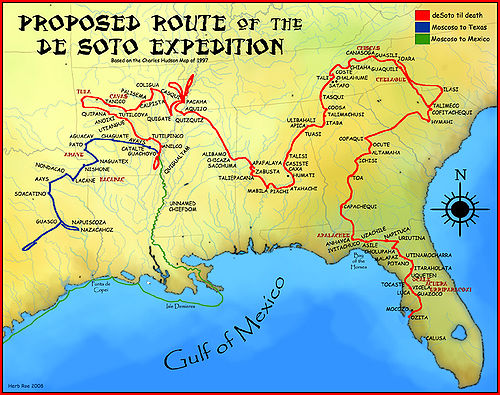

Historians have worked to trace the route of de Soto's expedition in North America, a controversial process over the years. Local politicians vied to have their localities associated with the expedition. The most widely used version of "De Soto's Trail" comes from a study commissioned by the Congress of the United States. A committee chaired by the anthropologist John R. Swanton published The Final Report of the United States De Soto Expedition Commission in 1939. Among other locations, Manatee County, Florida, claims an approximate landing site for de Soto and has a national memorial recognizing that event.[11] The first part of the expedition's course, until de Soto's battle at Mabila (a small fortress town in present-day central Alabama.[12]), is disputed only in minor details today. His route beyond Mabila is contested. Swanton reported the de Soto trail ran from there through Mississippi, Arkansas, and Texas.

Historians have more recently considered archeological reconstructions and the oral history of the various Native American peoples who recount the expedition. Most historical places have been overbuilt. More than 450 years have passed between the events and current history tellers (but some oral histories have been found to be highly accurate about historic events).

The Governor Martin Site at the former Apalachee village of Anhaica, located about a mile east of the present Florida capital in Tallahassee has been documented as definitively associated with de Soto's expedition. The Governor Martin Site was discovered by the archaeologist B. Calvin Jones in March 1987.

As of 2014, two sites on the shore of Orange Lake near Evinston, Florida, the White Ranch Site (8MR03538) in Marion County and the Richardson site (8AL100) in Alachua County, have been put forward as the site of the town of Potano visited by the de Soto expedition, and of the later mission of San Buenaventura de Potano.[13][14][15][16][17]

Many archaeologists believe the Parkin Site in Northeast Arkansas was the main town for the province of Casqui, which de Soto had recorded. They base this on similarities between descriptions from the journals of the de Soto expedition and artifacts of European origin discovered at the site in the 1960s.[18][19]

Theories of de Soto's route are based on the accounts of four chroniclers of the expedition.

• The first account of the expedition to be published was by the Gentleman of Elvas, an otherwise unidentified Portuguese knight who was a member of the expedition. His chronicle was first published in 1557. An English translation by Richard Hackluyt was published in 1609.[20]

• The King's factor (the agent responsible for the royal property) with the expedition, Luys Hernández de Biedma, wrote a report which still exists. The report was filed in the royal archives in Spain in 1544, and translated into English by Buckingham Smith and published in 1851.[21]

• De Soto's secretary, Rodrigo Ranjel, kept a diary, which has been lost, but apparently was used by Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés in writing his La historia general y natural de las Indias. Oviedo died in 1557, but the part of his work containing Ranjel's diary was not published until 1851. An English translation of Ranjel's report was published in 1904.

• The fourth chronicle is by Garcilaso de la Vega, El Inca. Garcilaso de la Vega was not a participant in the expedition. He wrote his account, La Florida, known in English as The Florida of the Inca, decades after the expedition, based on interviews with some survivors of the expedition. The book was first published in 1605. Historians have identified problems with using La Florida as a historical account. Milanich and Hudson warn against relying on Garcilaso, noting serious problems with the sequence and location of towns and events in his narrative, and add, "some historians regard Garcilaso's La Florida to be more a work of literature than a work of history."[22] Lankford characterizes Garcilaso's La Florida as a collection of "legend narratives", derived from a much-retold oral tradition of the survivors of the expedition.[23]

Milanich and Hudson warn that older translations of the chronicles are often "relatively free translations in which the translators took considerable liberty with the Spanish and Portuguese text."[24]

The chronicles describe de Soto's trail in relation to Havana, from which they sailed; the Gulf of Mexico, which they skirted inland then turned back to later; the Atlantic Ocean, which they approached during their second year; high mountains, which they traversed immediately thereafter; and dozens of other geographic features along their way, such as large rivers and swamps, at recorded intervals. Given that the natural geography has not changed much since de Soto's time, scholars have analyzed those journals with modern topographic intelligence, to render a more precise De Soto Trail.[10

No comments:

Post a Comment