Fort Hunt

Fort Hunt (1898-1946) - An Endicott Period Coastal Fort officially named Fort Hunt on 13 Apr 1899 after Bvt. Maj. General Henry J. Hunt. Closed in 1946.

Endicott Period (1890-1910)

Part of the Harbor Defense of the Potomac.

Construction on Fort Hunt did not begin until 1897 when worsening relations with Spain suddenly awakened the government to the sorry state of America's defenses. Once war was declared in March 1898, 48 men from the Fourth Coast Artillery were ordered to garrison the fort, even though only one of the four proposed batteries was completed. It was not until 1904 that the total armament of three 8-inch rifles, three 3-inch, and two 5-inch rapid firing guns was finally in place.

In spite of all the consternation engendered by the supposed threats of 1898, the new guns were never fired against an enemy. In common with all of Fort Hunt's subsequent manifestations, its life as a coastal battery was short-lived. Once the emergency that had created it had passed, the new post quickly assumed the usual uneventful rhythms of a half-forgotten peacetime garrison. Even in its heyday, it had never contained more that one company of 109 men.

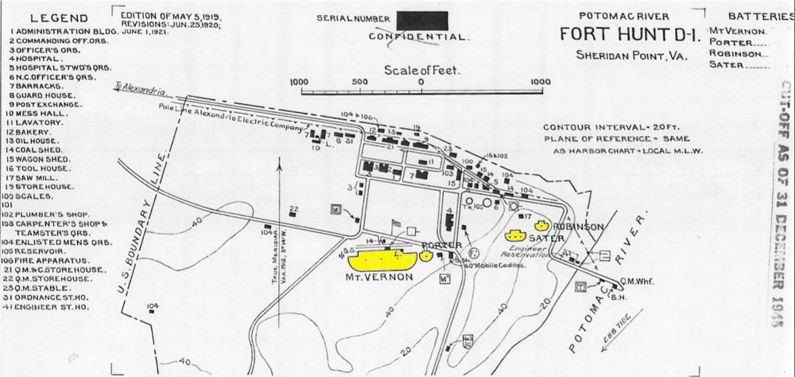

| Battery Click on Battery links below | No. | Caliber | Type Mount | Service Years | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Battery Mount Vernon | 3 | 8" | Disappearing | 1898-1917 | |

| Battery Porter | 1 | 5" | Balanced Pillar | 1901-1917 | |

| Battery Robinson | 1 | 5" | Balanced Pillar | 1901-1917 | |

| Battery Sater | 3 | 3" | Masking Parapet | 1904-1920 | |

| Source: CDSG | |||||

World War I (1917-1918)

With the outbreak of World War I, the Army decided that Fort Hunt's guns could be put to better use elsewhere. By 1918 all of the batteries had been dismantled and the armament transferred to other forts. Though no longer needed as a defensive post, Fort Hunt remained an integral part of the newly-constituted Army which emerged after World War I. As part of a vast reorganization meant to expand and modernize the Army, all of the 30-odd service schools were revamped and revitalized. In 1921, the Finance School was given Fort Hunt as its new home. Once again, however, the changing social and political climate dictated a shift in activities at Fort Hunt.

On 25 January 1922, the U.S. Army Band - "Pershing's Own" was organized and constituted at Fort Hunt. It would later move to Washington Barracks which became Fort Lesley J. McNair. After the band was deployed in WW II to North Africa, it would return from that deployment to Fort Myer where it continues until today.

As the post-War isolationist movement gained strength and popularity, a strong anti-militaristic mood began to take hold of the country. In 1922, Congress instructed the Army to drastically reduce its manpower, and to consolidate its functions. The Finance School fell victim to the new directives and was transferred back to offices in Washington in 1923.

For the next nine years, Fort Hunt was something of a "white elephant" for an Army which continued to reel under severe budgetary and personnel cutbacks. Except for a brief sojourn by a Signal Company, the fort was essentially abandoned. Although several local governments, a military academy, and the Department of Agriculture expressed an interest in using the land, Congress declined to transfer jurisdiction from the War Department. It was not until 1930 that Congress finally authorized the Secretary of War to transfer Fort Hunt to the Office of Public Buildings and Public Parks of the National Capital for development as a recreational site along the newly established George Washington Memorial Parkway.

World War II (1941-1945)

With the outbreak of World War II, the Army began a frantic search for additional installations and property. Particularly acute was the need for a secure interrogation center for prisoners of war. After wasting many weeks looking at isolated country estates and abandoned hotels, someone suddenly remembered Fort Hunt. The CCC camp was quickly moved to nearby Fort Belvoir in May 1942 and Fort Hunt transferred back to the War Department for a period not-to-exceed one year after the cessation of hostilities. For the next four years Fort Hunt would once again assume a decidedly military, though mysterious, air as it was transformed into a top secret Intelligence operation for the interrogation of German prisoners of war.

The old fort rapidly mushroomed into a major installation with 150 new buildings, lofty guard towers, and multiple electric fences. The operation was so secret that even the building plans were labeled "Officers' School" to throw curious workmen off the scent. The records for the Fort Hunt Intelligence operations have recently been declassified; and, we are just now beginning to learn some of the details of the activities there. Even individuals who lived next to the camp during the war are surprised today to learn that over 3400 prisoners passed through its gates. While they knew that it was in Army installation, they had no idea that prisoners of war were being processed there.

One of the reasons that secrecy was so vital was the simple fact that the operations at Fort Hunt were not exactly legal according to the Geneva Code of Conventions. Prisoners from whom the allies felt they might obtain valuable information, particularly submarine crews, were transferred to Fort Hunt immediately after their capture. There they were held incommunicado and questioned incessantly until they either volunteered what they knew or convinced the Americans that they were not going to talk. Only then were they transferred to a regular POW camp and the International Red Cross notified of their capture.

The average stay for a prisoner at Fort Hunt was three months, during which time he was questioned several times a day. The interrogating officers soon found, however, that they learned more from their prisoners by listening in to their private conversations over microphones hidden in the cells than they did in the formal interrogation sessions.

By November of 1946, World War II was over and the last German prisoner had left Fort Hunt. The combined Army/Navy Intelligence group closed down their operation and returned the land to the National Park Service which continued to develop the site as a recreational area.

Current Status

Location: Sheridan Point, Mount Vernon area, Fairfax County, Virginia

Maps & Images

Lat: 38.71659 Long: -77.053514

|

Sources:

- Roberts, Robert B., Encyclopedia of Historic Forts: The Military, Pioneer, and Trading Posts of the United States, Macmillan, New York, 1988, 10th printing, ISBN 0-02-926880-X, page 810-811

Links:

- North American Forts - Fort Hunt

- National Park Service History - Fort Hunt

- National Park Service History - Fort Hunt Park 1

- National Park Service History - Fort Hunt Park 2

- A Historical Sketch

- CDSG

Visited: 4 Apr 2009

No comments:

Post a Comment