The Ibeji Belief SystemAs the Yoruba believe that twins share the same combined

soul, when a newborn twin dies, the life of the other is

imperilled because the balance of his soul has become seri-

ously disturbed. To counteract this danger a special ritual is

carried out. After consulting the Babalawo, an artisan will

be commissioned to carve a small wooden figure as a sym-

bolic substitute for the soul of the deceased twin. If both

twins have died, two of these figures are made (Figure 2;

Jantzen & Bertisch, 1993; Mobolade, 1971; Stoll & Stoll,

1980).

These effigies are called Ere ibeji (from ‘ibi’ = born

and ‘eji’ = two; ere means sacred image). By virtue of his

immortal soul hosted by his ibeji, the departed twin remains as

powerful as the living one. The ibeji(s) will have

to be cared for by the parents or later on by the surviving

twin. Therefore, these figures are symbolically washed, fed

and clothed on a regular basis, according to a popular

Yoruba saying “dead ibeji expenses are expenses for the living”

(Courlander, 1973). According to these customs, the

mother enjoys certain privileges even if both her twins have

died (Stoll & Stoll, 1980).

| Yoruba people happen to exhibit the highest twinning rate in the world (Figure 3). |

In Caucasian populations, the

tendency for dizygotic twinning has been found to be

mainly hereditary (Meulemans, 1994). According to

Nylander (1979), its high frequency among Yoruba people

might also depend on dietary factors such as the consump-

tion of special species of yams containing oestrogenic

substances. Because of a high rate of premature delivery

and the lack of adequate medical care and health infrastruc-

tures in traditional Nigeria, the perinatal mortality of twins

used to be very high (Leroy, 1995). This explains why great

numbers of i beji statuettes have been produced in

Yorubaland and that they may have accumulated on the

domestic altar of certain families (Stoll & Stoll, 1980).

From the anthropological point of view, the ibeji belief

provides a means of helping Yoruba people to cope emo-

tionally with this high perinatal loss of twin babies (Leroy,

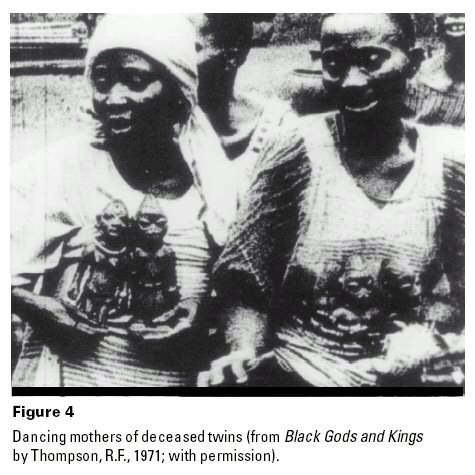

1995). At least once a year in some areas, Yoruba mothers

of deceased twins dance with their twin effigies, either held

tightly in the palms of their hands or tucked in the wrapper

about their waist (Figure 4). On these occasions the

mothers will also sing special songs in praise of the twins

(Thompson, 1971). Some of these songs emphasise the

belief that twins are related to colobus monkeys, the flesh

of which they are expressly forbidden to consume. One of

the popular Yoruba myths tells how twins came to earth as

the consequence of the confrontation of a farmer with the

monkeys in the ancient area of Ishokun (Courlander,

1973).

Two Yoruba songs in praise of twins

(Courlander, 1973; Olaleye-Oruene, 1983).

Fine looking twins, natives of Ishokun,

Descendants of treetop monkeys.

Twins saw the houses of the rich but did not go there,

Twins saw the houses of great personages but did not go there

Instead they entered the houses of the poor.

They made the poor rich, they clothed those who were naked.

Majestic and beautiful looking twins, natives of Ishokun,

Let me find means of eating, let me find means of drinking.

Majestic and beautiful looking twins, come and give me

The blessing of a child.

tendency for dizygotic twinning has been found to be

mainly hereditary (Meulemans, 1994). According to

Nylander (1979), its high frequency among Yoruba people

might also depend on dietary factors such as the consump-

tion of special species of yams containing oestrogenic

substances. Because of a high rate of premature delivery

and the lack of adequate medical care and health infrastruc-

tures in traditional Nigeria, the perinatal mortality of twins

used to be very high (Leroy, 1995). This explains why great

numbers of i beji statuettes have been produced in

Yorubaland and that they may have accumulated on the

domestic altar of certain families (Stoll & Stoll, 1980).

From the anthropological point of view, the ibeji belief

provides a means of helping Yoruba people to cope emo-

tionally with this high perinatal loss of twin babies (Leroy,

1995). At least once a year in some areas, Yoruba mothers

of deceased twins dance with their twin effigies, either held

tightly in the palms of their hands or tucked in the wrapper

about their waist (Figure 4). On these occasions the

mothers will also sing special songs in praise of the twins

(Thompson, 1971). Some of these songs emphasise the

belief that twins are related to colobus monkeys, the flesh

of which they are expressly forbidden to consume. One of

the popular Yoruba myths tells how twins came to earth as

the consequence of the confrontation of a farmer with the

monkeys in the ancient area of Ishokun (Courlander,

1973).

Two Yoruba songs in praise of twins

(Courlander, 1973; Olaleye-Oruene, 1983).

Fine looking twins, natives of Ishokun,

Descendants of treetop monkeys.

Twins saw the houses of the rich but did not go there,

Twins saw the houses of great personages but did not go there

Instead they entered the houses of the poor.

They made the poor rich, they clothed those who were naked.

Majestic and beautiful looking twins, natives of Ishokun,

Let me find means of eating, let me find means of drinking.

Majestic and beautiful looking twins, come and give me

The blessing of a child.

Ibeji StatuettesYorubas are the heirs of the prestigious artistic traditions

that prevailed in the ancient kingdom of Benin and the

sacred civilisation of Ifa. Yoruba traditional craftsmen have

hence produced some of the most elaborate and classical

examples of black African art (Bascom, 1973). Ibeji stat-

uettes are among the best-known Yoruba wooden carvings.

Although representing deceased babies, the latter are never

referred to as dead. Rather they are said to “have travelled”

or “gone to the market”. Ibeji effigies appear as wooden

erect adult beings about ten inches tall. They stand in a

“hands on the hips” position, generally on a round or quad-

rangular baseplate.

Following this general pattern, they nevertheless show

marked stylistic differences according to region of origin.

These differences are especially apparent in the shapes of

the heads, facial expressions, tribal scarring, and hairdos or

head covers. These latter are often dyed in bright blue with

indigo or even with dolly blue (Jantzen & Bertisch, 1993;

Thompson, 1971). Many ibejis are partly covered with a

crust of dried camwood powder. They may also present

facial smoothing and a patina due to frequent ritual use.

Very often, they are decorated with metal, cowrie-shell or

pearl necklaces, bracelets and belts. The colours of these

ornaments refer to deities such as Shango or Eshu whereas

cowrie shells, which were used in the past as currency,

remind the twins’ power either to bestow riches or to inflict

misfortune (Massa, 1999). Some ibejis are enclosed in a

large coat covered with eight rows of cowrie shells or deco-

rated with brightly coloured pearl designs. In some regions

this design may appear as a zigzag lightning pattern in

honour of the god Shango (Thompson, 1971). In this

context it is interesting to recall that worldwide, twins have

been linked to thunder. Even in the bible, Jesus Christ

called the twin apostles James and John “Boanerges”

(boanergeV) meaning “sons of thunder” (Leroy, 1995).

Transatlantic SpreadThe population of the West Indies and of the Eastern coast

of South America largely originates from the previous

African “Slave Coast” corresponding to the present-day

coast of Nigeria and Benin. It is therefore not surprising that

traditional Yoruba twin beliefs have been transposed in

Latin America. Such is the case of Brazilian traditions of the

Candoble and Macumba in the region of Salvador de Bahia

and of the Umbanda in Rio de Janeiro and Sao Paulo. These

traditions have maintained the Yoruba Orishas including the

sacred Ere Ibeji. In the Umbanda, the sacred twins are assim-

ilated to the Christian twin saints Cosmas and Damian

(Figure 5). The latter are colloquially called “the two young

men” and are celebrated at the end of September in a feast

especially devoted to children (Zuring, 1977).

that prevailed in the ancient kingdom of Benin and the

sacred civilisation of Ifa. Yoruba traditional craftsmen have

hence produced some of the most elaborate and classical

examples of black African art (Bascom, 1973). Ibeji stat-

uettes are among the best-known Yoruba wooden carvings.

Although representing deceased babies, the latter are never

referred to as dead. Rather they are said to “have travelled”

or “gone to the market”. Ibeji effigies appear as wooden

erect adult beings about ten inches tall. They stand in a

“hands on the hips” position, generally on a round or quad-

rangular baseplate.

Following this general pattern, they nevertheless show

marked stylistic differences according to region of origin.

These differences are especially apparent in the shapes of

the heads, facial expressions, tribal scarring, and hairdos or

head covers. These latter are often dyed in bright blue with

indigo or even with dolly blue (Jantzen & Bertisch, 1993;

Thompson, 1971). Many ibejis are partly covered with a

crust of dried camwood powder. They may also present

facial smoothing and a patina due to frequent ritual use.

Very often, they are decorated with metal, cowrie-shell or

pearl necklaces, bracelets and belts. The colours of these

ornaments refer to deities such as Shango or Eshu whereas

cowrie shells, which were used in the past as currency,

remind the twins’ power either to bestow riches or to inflict

misfortune (Massa, 1999). Some ibejis are enclosed in a

large coat covered with eight rows of cowrie shells or deco-

rated with brightly coloured pearl designs. In some regions

this design may appear as a zigzag lightning pattern in

honour of the god Shango (Thompson, 1971). In this

context it is interesting to recall that worldwide, twins have

been linked to thunder. Even in the bible, Jesus Christ

called the twin apostles James and John “Boanerges”

(boanergeV) meaning “sons of thunder” (Leroy, 1995).

Transatlantic SpreadThe population of the West Indies and of the Eastern coast

of South America largely originates from the previous

African “Slave Coast” corresponding to the present-day

coast of Nigeria and Benin. It is therefore not surprising that

traditional Yoruba twin beliefs have been transposed in

Latin America. Such is the case of Brazilian traditions of the

Candoble and Macumba in the region of Salvador de Bahia

and of the Umbanda in Rio de Janeiro and Sao Paulo. These

traditions have maintained the Yoruba Orishas including the

sacred Ere Ibeji. In the Umbanda, the sacred twins are assim-

ilated to the Christian twin saints Cosmas and Damian

(Figure 5). The latter are colloquially called “the two young

men” and are celebrated at the end of September in a feast

especially devoted to children (Zuring, 1977).

In Cuba, a legend of the Santeria belief tells how the

twins born from Oshun, the goddess of water and preg-

nancy, saved the god Shango (see above). In this tradition,

the god of twins is called Jimaguas and is represented by

two statuettes, male and female, united by their navels and

ritually used to cure the sick (Zuring, 1977).

ConclusionSuperstitions and customs pertaining to twins are universal

and often share converging features among cultures without

any mutual geographical or temporal contact (Leroy, 1995).

This would point to the twin cult as one of the earliest

religious beliefs that has been widely spread and diversified

along human history. In relation with their high frequency

and high perinatal mortality of twins, the Yoruba have

developed special beliefs and customs related to twins and

allowing, in particular, to ritualise the bereavement process

when one or both of the twins die.

ReferencesBascom, W. (1973). African art in cultural perspective. New

York & London: W.W. Norton & Cy.

Bolajildowu, E. (1973). African traditional religion. A definition.

London: SCM Press Ltd.

Cavalli-Sforza, L. L., Menozzi, P., & Piazza, A. (1993). The

history and geography of human genes. New Jersey: Princeton

University Press.

Chappel, T. H. (1974). The Yoruba cult of twins in historical

perspective. Africa, 49, 250–265.

Courlander, H. (1973). Tales of Yoruba gods and heroes. New

York: Crown Publishing Inc.

Jantzen, H., & Bertisch, L. (1993). Doppel Leben, Ibeji Zwilling

Figuren [Double life, Ibeji twin figures]. Munchen: Missio

Aachen, Hirmer Verlag.

Leroy, F. (1995). Les jumeaux dans tous leurs états. Louvain –

la -Neuve [ Twins in ever y st at e], Belgiu m: Deboeck

Université.

Meulemans,W. (1994). The genetics of dizygotic twinning.

Leuven, Belgium: Leuven University Press.

Ma ssa, G. (19 99). La maternité dans l’art d’Afrique noire

[Maternity in black African art]. France: Sépia.

Mobolade, T. (1971). Ibeji customs in Yorubaland. African Arts,

4(3), 14–15.

Nylander, P. P. S. (1979). The twinning incidence in Nigeria.

Acta Geneticae Medicae et Gemellologiae, 28, 261–263.

Radin, P. (1974). Monotheism among primitive people. New

York: Alan and Unwin.

Olaleye-Oruene, T. (1983). Cultic powers of Yoruba twins.

Acta Geneticae Medicae et Gemellologiae, 32, 221–228.

Stoll, M., & Stoll, G. (1980). Ibeji. Bad Aibling, Dusseldorf:

Eds Veit Gärtner.

Thomp so n, R. F. ( 1971). Black gods and kings .

Bloomingon/London: UCLA, Indiana University Press.

Watson, E., Bauer, K., Aman, R., Weiss, G., von Haeseler, A.,

& Pääbo, S. (1996). mtDNA sequences diversity in Africa.

American Journal of Genetics, 59, 437–454.

Zuring, J. (1977). Tweelingen in Afrika [Twins in Africa]. Tilburg,

Holland: H. Gianotten.

Twin Research April 2002

twins born from Oshun, the goddess of water and preg-

nancy, saved the god Shango (see above). In this tradition,

the god of twins is called Jimaguas and is represented by

two statuettes, male and female, united by their navels and

ritually used to cure the sick (Zuring, 1977).

ConclusionSuperstitions and customs pertaining to twins are universal

and often share converging features among cultures without

any mutual geographical or temporal contact (Leroy, 1995).

This would point to the twin cult as one of the earliest

religious beliefs that has been widely spread and diversified

along human history. In relation with their high frequency

and high perinatal mortality of twins, the Yoruba have

developed special beliefs and customs related to twins and

allowing, in particular, to ritualise the bereavement process

when one or both of the twins die.

ReferencesBascom, W. (1973). African art in cultural perspective. New

York & London: W.W. Norton & Cy.

Bolajildowu, E. (1973). African traditional religion. A definition.

London: SCM Press Ltd.

Cavalli-Sforza, L. L., Menozzi, P., & Piazza, A. (1993). The

history and geography of human genes. New Jersey: Princeton

University Press.

Chappel, T. H. (1974). The Yoruba cult of twins in historical

perspective. Africa, 49, 250–265.

Courlander, H. (1973). Tales of Yoruba gods and heroes. New

York: Crown Publishing Inc.

Jantzen, H., & Bertisch, L. (1993). Doppel Leben, Ibeji Zwilling

Figuren [Double life, Ibeji twin figures]. Munchen: Missio

Aachen, Hirmer Verlag.

Leroy, F. (1995). Les jumeaux dans tous leurs états. Louvain –

la -Neuve [ Twins in ever y st at e], Belgiu m: Deboeck

Université.

Meulemans,W. (1994). The genetics of dizygotic twinning.

Leuven, Belgium: Leuven University Press.

Ma ssa, G. (19 99). La maternité dans l’art d’Afrique noire

[Maternity in black African art]. France: Sépia.

Mobolade, T. (1971). Ibeji customs in Yorubaland. African Arts,

4(3), 14–15.

Nylander, P. P. S. (1979). The twinning incidence in Nigeria.

Acta Geneticae Medicae et Gemellologiae, 28, 261–263.

Radin, P. (1974). Monotheism among primitive people. New

York: Alan and Unwin.

Olaleye-Oruene, T. (1983). Cultic powers of Yoruba twins.

Acta Geneticae Medicae et Gemellologiae, 32, 221–228.

Stoll, M., & Stoll, G. (1980). Ibeji. Bad Aibling, Dusseldorf:

Eds Veit Gärtner.

Thomp so n, R. F. ( 1971). Black gods and kings .

Bloomingon/London: UCLA, Indiana University Press.

Watson, E., Bauer, K., Aman, R., Weiss, G., von Haeseler, A.,

& Pääbo, S. (1996). mtDNA sequences diversity in Africa.

American Journal of Genetics, 59, 437–454.

Zuring, J. (1977). Tweelingen in Afrika [Twins in Africa]. Tilburg,

Holland: H. Gianotten.

Twin Research April 2002

No comments:

Post a Comment