Proto-literate period[edit]

The cuneiform script proper developed from pictographic proto-writing in the late 4th millennium B.C.E. Mesopotamia's "proto-literate" period spans roughly the 35th to 32nd centuries. The first documents unequivocally written in the Sumerian language date to c. the 31st century, found at Jemdet Nasr.

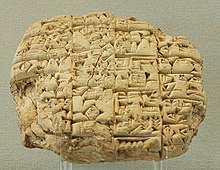

Originally, pictographs were either drawn on clay tablets in vertical columns with a sharpened reed stylus, or incised in stone. This early style lacked the characteristic wedge shape of the strokes.

Certain signs to indicate names of gods, countries, cities, vessels, birds, trees, etc., are known as determinatives, and were the Sumerian signs of the terms in question, added as a guide for the reader. Proper names continued to be usually written in purely "logographic" fashion.

The earliest known Sumerian king whose name appears on contemporary cuneiform tablets is Enmebaragesi of Kish. Surviving records only very gradually become less fragmentary and more complete for the following reigns, but by the end of the pre-Sargonic period, it had become standard practice for each major city-state to date documents by year-names commemorating the exploits of its lugal (king).

From about 2900 B.C.E., many pictographs began to lose their original function, and a given sign could have various meanings depending on context. The sign inventory was reduced from some 1,500 signs to some 600 signs, and writing became increasingly phonological. Determinative signs were re-introduced to avoid ambiguity. Cuneiformwriting proper thus arises from the more primitive system of pictographs at about that time (Early Bronze Age II).

Archaic cuneiform[edit]

Further information: Liste der archaischen Keilschriftzeichen

In the mid-3rd millennium B.C.E., writing direction was changed to left to right in horizontal rows (rotating all of the pictographs 90° counter-clockwise in the process), and a new wedge-tipped stylus was used which was pushed into the clay, producing wedge-shaped ("cuneiform") signs; these two developments made writing quicker and easier. By adjusting the relative position of the tablet to the stylus, the writer could use a single tool to make a variety of impressions.

Cuneiform tablets could be fired in kilns to provide a permanent record, or they could be recycled if permanence was not needed. Many of the clay tablets found by archaeologists were preserved because they were fired when attacking armies burned the building in which they were kept.

The script was also widely used on commemorative stelae and carved reliefs to record the achievements of the ruler in whose honor the monument had been erected.

The spoken language consisted of many similar sounds, and in the beginning similar sounding words such as "life" [til] and "arrow" [ti] were described in writing by the same symbol. After the Semites conquered Southern Mesopotamia, some signs gradually changed from being pictograms to syllabograms, most likely to make things clearer in writing. In that way the sign for the word "arrow" would become the sign for the sound "ti". If a sound represented many different words the words would all have different signs, for instance the syllable "gu" had fourteen different symbols. When the words had similar meaning but very different sounds they were written with the same symbol. For instance "tooth" [zu], "mouth" [ka] and "voice" [gu] were all written with the symbol for "voice". To be more accurate they started adding to signs or combine two signs to define the meaning. They used either geometrical patterns or another cuneiform sign.[2]

No comments:

Post a Comment