Trans-Alaska Pipeline System

| Trans-Alaska Pipeline System | |

|---|---|

The trans-Alaska oil pipeline,

as it zig-zags across the landscape | |

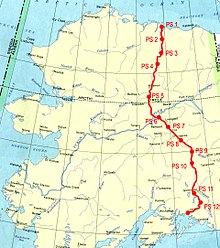

Location of trans-Alaska pipeline

| |

| Location | |

| Country | Alaska, United States |

| Coordinates | 70°15′26″N 148°37′8″WCoordinates: 70°15′26″N 148°37′8″W |

| General direction | North-South |

| From | Prudhoe Bay, Alaska |

| Passes through | Deadhorse Delta Junction Fairbanks Fox Glennallen North Pole |

| To | Valdez, Alaska |

| Runs alongside | Dalton Highway Richardson Highway Elliott Highway |

| General information | |

| Type | Pump stations |

| Owner | Alyeska Pipeline Service Company |

| Partners | BP ConocoPhillips Exxon Mobil Koch Industries Chevron Corporation |

| Commissioned | 1977[1][2][3] |

| Technical information | |

| Length | 800.3 mi (1,288.0 km) |

| Maximum discharge | 2.136 MMbbl/d (339,600 m3/d) |

| Diameter | 48 in (1,219 mm) |

| No. of pumping stations | 12 |

The Trans-Alaska Pipeline System (TAPS) includes the trans-Alaska crude-oil pipeline, 11 pump stations, several hundred miles of feeder pipelines, and the Valdez Marine Terminal. TAPS is one of the world's largest pipeline systems. It is commonly called the Alaska pipeline, trans-Alaska pipeline, or Alyeska pipeline, (or the pipeline as referred to in Alaska), but those terms technically apply only to the 800 miles (1,287 km) of the pipeline with the diameter of 48 inches (1.22 m) that conveys oil from Prudhoe Bay to Valdez, Alaska. The crude oil pipeline is privately owned by the Alyeska Pipeline Service Company.

The pipeline was built between 1974 and 1977, after the 1973 oil crisis caused a sharp rise in oil prices in the United States. This rise made exploration of the Prudhoe Bay oil field economically feasible. Environmental, legal, and political debates followed the discovery of oil at Prudhoe Bay in 1968, and the pipeline was built only after the oil crisis provoked the passage of legislation designed to remove legal challenges to the project.

In building the pipeline, engineers faced a wide range of difficulties, stemming mainly from the extreme cold and the difficult, isolated terrain. The construction of the pipeline was one of the first large-scale projects to deal with problems caused by permafrost, and special construction techniques had to be developed to cope with the frozen ground. The project attracted tens of thousands of workers to Alaska, causing a boomtown atmosphere in Valdez, Fairbanks, and Anchorage.

The first barrel of oil traveled through the pipeline in the summer of 1977,[1][2][3][4] with full-scale production by the end of the year. Several notable incidents of oil leakage have occurred since, including those caused by sabotage, maintenance failures, and bullet holes. As of 2010, it had shipped almost 16 billion barrels (2.5×109 m3) of oil. The pipeline has been shown capable of delivering over 2 million barrels of oil per day but nowadays usually operates at a fraction of maximum capacity. If flow were to stop or throughput were too little, the line could freeze. The pipeline could be extended and used to transport oil produced from proposed drilling projects in the nearby Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR).

Contents

Origins[edit]

Iñupiat people on the North Slope of Alaska had mined oil-saturated peat for possibly thousands of years, using it as fuel for heat and light. Whalers who stayed at Point Barrow saw the substance the Iñupiat called pitch and recognized it as petroleum. Charles Brower, a whaler who settled at Barrow and operated trading posts along the arctic coast, directed geologist Alfred Hulse Brooks to oil seepages at Cape Simpson and Fish Creek in the far north of Alaska, east of the village of Barrow.[5] Brooks' report confirmed the observations of Thomas Simpson, an officer of the Hudson's Bay Company who first observed the seepages in 1836.[6] Similar seepages were found at the Canning River in 1919 by Ernest de Koven Leffingwell.[7] Following the First World War, as the United States Navy converted its ships from coal to fuel oil, a stable supply of oil became important to the U.S. government. Accordingly, President Warren G. Harding established by executive order a series of Naval Petroleum Reserves (NPR-1 through -4) across the United States. These reserves were areas thought to be rich in oil and set aside for future drilling by the U.S. Navy. Naval Petroleum Reserve No. 4 was sited in Alaska's far north, just south of Barrow, and encompassed 23,000,000 acres (93,078 km2).[8] Other Naval Petroleum Reserves were embroiled in controversy over government corruption in the Teapot Dome Scandal.

The first explorations of NPR-4 were undertaken by the U.S. Geological Survey from 1923 to 1925 and focused on mapping, identifying and characterizing coal resources in the western portion of the reserve and petroleum exploration in the eastern and northern portions of the reserve. These surveys were primarily pedestrian in nature; no drilling or remote sensing techniques were available at the time. These surveys named many of the geographic features of the areas explored, including the Philip Smith Mountains and quadrangle.[9][10]

The petroleum reserve lay dormant until the Second World War provided an impetus to explore new oil prospects. The first renewed efforts to identify strategic oil assets were a two pronged survey using bush aircraft, local Inupiat guides, and personnel from multiple agencies to locate reported seeps. Ebbley and Joesting reported on these initial forays in 1943. Starting in 1944, the U.S. Navy funded oil exploration near Umiat Mountain, on the Colville River in the foothills of the Brooks Range.[11] Surveyors from the U.S. Geological Survey spread across the petroleum reserve and worked to determine its extent until 1953, when the Navy suspended funding for the project. The USGS found several oil fields, most notably the Alpine and Umiat Oil Field, but none were cost-effective to develop.[12]

Four years after the Navy suspended its survey, Richfield Oil Corporation (later Atlantic Richfield and ARCO) drilled an enormously successful oil well near the Swanson River in southern Alaska, near Kenai.[13] The resulting Swanson River Oil Field was Alaska's first major commercially producing oil field, and it spurred the exploration and development of many others.[14] By 1965, five oil and 11 natural gas fields had been developed. This success and the previous Navy exploration of its petroleum reserve led petroleum engineers to the conclusion that the area of Alaska north of the Brooks Range surely held large amounts of oil and gas.[15] The problems came from the area's remoteness and harsh climate. It was estimated that between 200,000,000 barrels (32,000,000 m3) and 500,000,000 barrels (79,000,000 m3) of oil would have to be recovered to make a North Slope oil field commercially viable.[13]

In 1967, Atlantic Richfield (ARCO) began detailed survey work in the Prudhoe Bay area. By January 1968, reports began circulating that natural gas had been discovered by a discovery well.[16] On March 12, 1968, an Atlantic Richfield drilling crew hit paydirt.[17] A discovery well began flowing at the rate of 1,152 barrels (183.2 m3) of oil per day.[16] On June 25, ARCO announced that a second discovery well likewise was producing oil at a similar rate. Together, the two wells confirmed the existence of the Prudhoe Bay Oil Field. The new field contained more than 25 billion barrels (4.0×109 m3) of oil, making it the largest in North America and the 18th largest in the world.[17]

The problem soon became how to develop the oil field and ship product to U.S. markets. Pipeline systems represent a high initial cost but lower operating costs, but no pipeline of the necessary length had yet been constructed. Several other solutions were offered. Boeing proposed a series of gigantic 12-engine tanker aircraft to transport oil from the field, the Boeing RC-1.[18] General Dynamics proposed a line of tanker submarines for travel beneath the Arctic ice cap, and another group proposed extending the Alaska Railroad to Prudhoe Bay.[19] Ice breaking oil tankers were proposed to transport the oil directly from Prudhoe Bay, but the feasibility was questioned.

To test this, in 1969 Humble Oil and Refining Company sent a specially fitted oil tanker, the SS Manhattan, to test the feasibility of transporting oil via ice-breaking tankers to market.[20] The Manhattan was fitted with an ice-breaking bow, powerful engines, and hardened propellers before successfully traveling the Northwest Passage from the Atlantic Ocean to the Beaufort Sea. During the voyage, the ship suffered damage to several of its cargo holds, which flooded with seawater. Wind-blown ice forced the Manhattan to change its intended route from the M'Clure Strait to the smaller Prince of Wales Strait. It was escorted back through the Northwest Passage by a Canadian Coast Guard icebreaker, the CCGS John A. Macdonald. Although the Manhattan transited the Northwest Passage again in the summer of 1970, the concept was considered too risky.[21] A pipeline was thus the only viable system for transporting the oil to the nearest port free of pack-ice, almost 800 miles (1,300 km) away at Valdez.

Forming Alyeska[edit]

In February 1969, before the SS Manhattan had even sailed from its East Coast starting point, the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System (TAPS), an unincorporated joint group created by ARCO, British Petroleum, and Humble Oil in October 1968,[22] asked for permission from the United States Department of the Interior to begin geological and engineering studies of a proposed oil pipeline route from Prudhoe Bay to Valdez, across Alaska. Even before the first feasibility studies began, the oil companies had chosen the approximate route of the pipeline.[23] Permission was given, and teams of engineers began drilling core samples and surveying in Alaska.

Because TAPS hoped to begin laying pipe by September 1969, substantial orders were placed for steel pipeline 48 inches (122 cm) in diameter.[24] No American company manufactured pipe of that specification, so three Japanese companies—Sumitomo Metal Industries Ltd., Nippon Steel Corporation, and Nippon Kokan Kabushiki Kaisha—received a $100 million contract for more than 800 miles (1280 km) of pipeline. At the same time, TAPS placed a $30 million order for the first of the enormous pumps that would be needed to push the oil through the pipeline.[25]

In June 1969, as the SS Manhattan traveled through the Northwest Passage, TAPS formally applied to the Interior Department for a permit to build an oil pipeline across 800 miles (1,300 km) of public land—from Prudhoe Bay to Valdez.[26] The application was for a 100-foot (30.5 m) wide right of way to build a subterranean 48-inch (122-centimeter) pipeline including 11 pumping stations. Another right of way was requested to build a construction and maintenance highway paralleling the pipeline. A document of just 20 pages contained all of the information TAPS had collected about the route up to that stage in its surveying.[27]

The Interior Department responded by sending personnel to analyze the proposed route and plan. Max Brewer, an arctic expert in charge of the Naval Arctic Research Laboratory at Barrow, concluded that the plan to bury most of the pipeline was completely unfeasible because of the abundance of permafrost along the route. In a report, Brewer said the hot oil conveyed by the pipeline would melt the underlying permafrost, causing the pipeline to fail as its support turned to mud. This report was passed along to the appropriate committees of the U.S. House and Senate, which had to approve the right-of-way proposal because it asked for more land than authorized in the Mineral Leasing Act of 1920 and because it would break a development freeze imposed in 1966 by former Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall.[28]

Udall imposed the freeze on any projects involving land claimed by Alaska Natives in hopes that an overarching Native claims settlement would result.[29] In the fall of 1969, the Department of the Interior and TAPS set about bypassing the land freeze by obtaining waivers from the various native villages that had claims to a portion of the proposed right of way. By the end of September, all the relevant villages had waived their right-of-way claims, and Secretary of the Interior Wally Hickel asked Congress to lift the land freeze for the entire TAPS project. After several months of questioning by the House and Senate committees with oversight of the project, Hickel was given the authority to lift the land freeze and give the go-ahead to TAPS.

TAPS began issuing letters of intent to contractors for construction of the "haul road", a highway running the length of the pipeline route to be used for construction. Heavy equipment was prepared, and crews prepared to go to work after Hickel gave permission and the snow melted.[30] Before Hickel could act, however, several Alaska Native and conservation groups asked a judge in Washington, D.C., to issue an injunction against the project. Several of the native villages that had waived claims on the right of way reneged because TAPS had not chosen any Native contractors for the project and the contractors chosen were not likely to hire Native workers.[31]

On April 1, 1970, Judge George Luzerne Hart, Jr., of the United States District Court for the District of Columbia, ordered the Interior Department to not issue a construction permit for a section of the project that crossed one of the claims.[32] Less than two weeks later, Hart heard arguments from conservation groups that the TAPS project violated the Mineral Leasing Act and the National Environmental Policy Act, which had gone into effect at the start of the year. Hart issued an injunction against the project, preventing the Interior Department from issuing a construction permit and halting the project in its tracks.[33]

After the Department of the Interior was stopped from issuing a construction permit, the unincorporated TAPS consortium was reorganized into the new incorporated Alyeska Pipeline Service Company.[34] Former Humble Oil manager Edward L. Patton was put in charge of the new company and began to lobby strongly in favor of an Alaska Native claims settlement to resolve the disputes over the pipeline right of way.[35]

Opposition[edit]

Opposition to construction of the pipeline primarily came from two sources: Alaska Native groups and conservationists. Alaska Natives were upset that the pipeline would cross the land traditionally claimed by a variety of native groups, but no economic benefits would accrue to them directly. Conservationists were angry at what they saw as an incursion into America's last wilderness.[according to whom?][36] Both opposition movements launched legal campaigns to halt the pipeline and were able to delay construction until 1973.

Conservation objections[edit]

Although conservation groups and environmental organizations had voiced opposition to the pipeline project before 1970, the introduction of the National Environmental Policy Act allowed them legal grounds to halt the project. Arctic engineers had raised concerns about the way plans for a subterranean pipeline showed ignorance of Arctic engineering and permafrost in particular.[37] A clause in NEPA requiring a study of alternatives and another clause requiring an environmental impact statement turned those concerns into tools used by the Wilderness Society, Friends of the Earth, and the Environmental Defense Fund in their Spring 1970 lawsuit to stop the project.[38]

The injunction against the project forced Alyeska to do further research throughout the summer of 1970. The collected material was turned over to the Interior Department in October 1970,[39] and a draft environmental impact statement was published in January 1971.[40] The 294-page statement drew massive criticism, generating more than 12,000 pages of testimony and evidence in Congressional debates by the end of March.[41] Criticisms of the project included its effect on the Alaska tundra, possible pollution, harm to animals, geographic features, and the lack of much engineering information from Alyeska. One element of opposition the report quelled was the discussion of alternatives. All the proposed alternatives—extension of the Alaska Railroad, an alternative route through Canada, establishing a port at Prudhoe Bay, and more—were deemed to pose more environmental risks than construction of a pipeline directly across Alaska.[40]

Opposition also was directed at the building of the construction and maintenance highway parallel to the pipeline. Although a clause in Alyeska's pipeline proposal called for removal of the pipeline at a certain point, no such provision was made for removal of the road. Sydney Howe, president of the Conservation Foundation, warned: "The oil might last for fifty years. A road would remain forever."[42] This argument relied upon the slow growth of plants and animals in far northern Alaska due to the harsh conditions and short growing season. In testimony, an environmentalist argued that arctic trees, though only a few feet tall, had been seedlings "when George Washington was inaugurated".[43]

The portion of the environmental debate with the biggest symbolic impact took place when discussing the pipeline's impact on caribou herds.[44] Environmentalists proposed that the pipeline would have an effect on caribou similar to the effect of the U.S. transcontinental railroad on the American Bison population of North America.[44] Pipeline critics said the pipeline would block traditional migration routes, making caribou populations smaller and making them easier to hunt. This idea was exploited in anti-pipeline advertising, most notably when a picture of a forklift carrying several legally shot caribou was emblazoned with the slogan, "There is more than one way to get caribou across the Alaska Pipeline".[45] The use of caribou as an example of the pipeline's environmental effects reached a peak in the spring of 1971, when the draft environmental statement was being debated.[45]

The pipeline interferes with Caribou migration routes but crossing points were installed to help limit disruption.

Native objections[edit]

In 1902, the United States Department of Agriculture set aside 16,000,000 acres (64,750 km2) of Southeast Alaska as the Tongass National Forest.[46] Tlingit natives who lived in the area protested that the land was theirs and had been unfairly taken. In 1935, Congress passed a law allowing the Tlingits to sue for recompense, and the resulting case dragged on until 1968, when a $7.5 million settlement was reached.[47] Following the Native lawsuit to halt work on the Trans-Alaska Pipeline, this precedent was frequently mentioned in debate, causing pressure to resolve the situation more quickly than the 33 years it had taken for the Tlingits to be satisfied.[48] Between 1968 and 1971, a succession of bills were introduced into the U.S. Congress to compensate statewide Native claims.[49] The earliest bill offered $7 million, but this was flatly rejected.[50]

The Alaska Federation of Natives, which had been created in 1966, hired former United States Supreme Court justice Arthur Goldberg, who suggested that a settlement should include 40 million acres (160,000 km2) of land and a payment of $500 million.[50] The issue remained at a standstill until Alyeska began lobbying in favor of a Native claims act in Congress in order to lift the legal injunction against pipeline construction.[50] In October 1971, President Richard Nixon signed the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA). Under the act, Native groups would renounce their land claims in exchange for $962.5 million and 148.5 million acres (601,000 km2) in federal land.[51] The money and land were split up among village and regional corporations, which then distributed shares of stock to Natives in the region or village. The shares paid dividends based on both the settlement and corporation profits.[52] To pipeline developers, the most important aspect of ANCSA was the clause dictating that no Native allotments could be selected in the path of the pipeline.[53]

Another objection of the natives was the potential for the pipeline to disrupt a traditional way of life. Many natives were worried that the disruption caused by the pipeline would scare away the whales and caribou that are relied upon for food.[54]

No comments:

Post a Comment