Gargoyles....and spooky things galore.......

Architecture[edit]

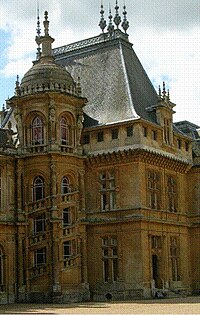

Vanderbilt commissioned prominent New York architect Richard Morris Hunt, who had previously designed houses for various Vanderbilt family members, to design the house in the Châteauesque style, using French Renaissance chateaus that Vanderbilt and Hunt had visited in early 1889, including Château de Blois, Chenonceau and Chambord in France and Waddesdon Manor in England, as inspiration with their steeply pitched roofs, turrets and sculptural ornamentation.[3] Hunt sited the four-story Indiana limestone-built home to face east with a 375-foot facade to fit into the mountainous topography behind. The facade is asymmetrically balanced with two projecting wings connecting to the entrance tower with an open loggia to the left side and a windowed arcade to the right which held the Winter Garden that was fashionable during the Victorian era. The entrance tower contains a series of windows with decorated jambs that extend from the front door to the most decorated dormer at Biltmore on the fourth floor. The carved decorations include trefoils, flowing tracery, rosettes and at prominent lookouts, gargoyles. The large gargoyles are purely for decoration instead of their normal use to direct water away from a building. The staircase is one of the more prominent features of the east facade, with its three-story, highly decorated winding balustrade with carved statues of St. Louis and Joan of Arc by the Austrian-born architectural sculptor Karl Bitter.

The south facade has the smallest dimensions for the house and is dominated by three large dormers on the east side and a polygonal turret on the west side. An arbor is attached to the house and is accessed from the library which is located on the ground floor. On the north end of the house, Hunt placed the attached stables, carriage house and its courtyard to protect the house and gardens from the wind. The 12,000-square-foot complex housed Vanderbilt's prized driving horses and the carriage house opposite the stables stored his 20 carriages in addition to any of his guest's carriages.

The rear western elevation is less elaborate than the front facade, with some windows not having any decoration at all. Two matching polygonal towers in the center are connected to the polygonal south turret by an open loggia that opens the main rooms of the house to the views of the Blue Ridge Mountains in the distance. The loggia is decorated overhead with terracotta tiles set in a herringbone pattern. The self-supporting ceramic tile vault and arch system was used extensively inside and outside of Biltmore, and was patented by Rafael Guastavino, a Spanish architect and engineer, who personally supervised the installation. The limestone columns were carved to reflect the sunlight in aesthetically pleasing and varied ways per Vanderbilt's wish. The rusticated base is a contrast to the smooth limestone used on the remainder of the house.

The steeply pitched roof is punctuated by 16 chimneys and covered with slate tiles that were affixed one by one. Each tile was drilled at the corners and wired onto the attic’s steel infrastructure. Copper flashing was then installed at the junctions to prevent water from penetrating. The fanciful flashing on the ridge of the roof was embossed with George Vanderbilt’s initials and motifs from his family crest, though the original gold leaf no longer survives.[4]

Biltmore House had electricity from the time it was built. With electricity less safe and fire more of a danger at the time, the house had separate sections divided by brick fire walls.[5]

Vanderbilt paid little attention to the family business or his own investments, and it is believed that the construction and upkeep of Biltmore depleted much of his inheritance.

Comments

Post a Comment