Pierre Charles L'Enfant

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

"Pierre L'Enfant" redirects here. For other people of the same name, see Pierre L'Enfant (disambiguation).

| Pierre "Peter" Charles L'Enfant | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | August 2, 1754 Paris, Île-de-France, France |

| Died | June 14, 1825 (aged 70) Prince George's County, Maryland, U.S. |

| Nationality | French (French-American) |

| Other names | Peter Charles L'Enfant |

| Ethnicity | French American |

| Education | Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture |

| Occupation | Architect, civil engineer, soldier[1] |

| Organization | United States Army[1] |

| Known for | L'Enfant Plan |

| Title | Major[1] |

Contents

Early life and education

L'Enfant was born in Paris, France on August 9, 1754, the third child and second son of Marie Charlotte L'Enfant (aged 25 and the daughter of a minor marine official at court) and Pierre L'Enfant (1704–1787), a painter with a good reputation in the service of King Louis XV. In 1758, his brother Pierre Joseph died at the age of six, and Pierre Charles became the eldest son. He studied art at the Royal Academy in the Louvre, as well as with his father at the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture. He left school in France to enlist in the American Revolutionary War on the side of the rebels.Career

Military service

L'Enfant was recruited by Pierre Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais to join in the American Revolutionary War in the American colonies. He arrived in 1777 at the age of 23, and served as a military engineer in the Continental Army with Major General Lafayette.[2] Despite his aristocratic origins, L'Enfant closely identified with the United States, adopting the name Peter.[3][4][5][6] He was wounded at the Siege of Savannah in 1779, but recovered and served in General George Washington's staff as a Captain of Engineers for the remainder of the Revolutionary War. During the war, L'Enfant was with George Washington at Valley Forge. While there, the Marquis de Lafayette commissioned L'Enfant to paint a portrait of Washington. L'Enfant was promoted by brevet to Major of Engineers on May 2, 1783, in recognition of his service to American liberty.[7]After the war, L'Enfant designed the badge of the Society of the Cincinnati, shaped as an eagle, at the request of Washington. He was sent to France to have insignias made for members of the Society, a group of veterans of the war.[8]

Architect and planner

Post–Revolutionary War

Following the war, L'Enfant established a successful and highly profitable civil engineering firm in New York City. He achieved some fame as an architect by redesigning the City Hall in New York for the First Congress in Federal Hall.[9] He also designed coins, medals, furniture and houses of the wealthy, and he was a friend of Alexander Hamilton.While L'Enfant was in New York City, he was initiated into Freemasonry. His initiation took place on April 17, 1789, at Holland Lodge No. 8 F&AM, which the Grand Lodge of New York F&AM had chartered in 1787. L'Enfant took only the first of three degrees offered by the lodge and did not progress further in Freemasonry.[10][11]

Plan for federal capital city

See also: L'Enfant Plan

The new Constitution of the United States, which took effect in 1789, gave Congress authority to establish a federal district up to ten miles square in size.

L'Enfant had already written to President Washington, asking to be

commissioned to plan the city, but a decision on the capitol was put on

hold until July 1790 when the 1st Congress passed the Residence Act.[12] The legislation, which was the result of a compromise brokered by Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson, specified the new capital be situated on the Potomac River, at some location between the Eastern Branch (the Anacostia River) and the Connogochegue, near Hagerstown, Maryland.

The Residence Act gave authority to President Washington to appoint

three commissioners to oversee the survey of the federal district and

"according to such Plans, as the President shall approve," provide

public buildings to accommodate the Federal government in 1800.[13][14]President Washington appointed L'Enfant in 1791 to plan the new capital city (later named the City of Washington) under the supervision of three Commissioners, whom Washington had appointed to oversee the planning and development of the federal territory that would later become the District of Columbia.[15] Thomas Jefferson, who worked alongside President Washington in overseeing the plans for the capital, sent L'Enfant a letter outlining his task, which was to provide a drawing of suitable sites for the federal city and the public buildings. Though Jefferson had modest ideas for the Capital, L'Enfant saw the task as far more grandiose, believing he was not only locating the capital, but also devising the city plan and designing the buildings.[16]

L'Enfant arrived in Georgetown on March 9, 1791, and began his work, from Suter's Fountain Inn.[17] Washington arrived on March 28, to meet with L'Enfant and the Commissioners for several days.[18] On June 22, L'Enfant presented his first plan for the federal city to the President.[19][20][21] On August 19, he appended a new map to a letter that he sent to the President.[20][22]

President Washington retained one of L'Enfant's plans, showed it to Congress, and later gave it to the three Commissioners.[23][24] The U.S. Library of Congress now holds both the plan that Washington apparently gave to the Commissioners and an undated anonymous survey map that the Library considers L'Enfant to have drawn before August 19, 1791.[23][25] The survey map may be one that L'Enfant appended to his August 19 letter to the President.[26]

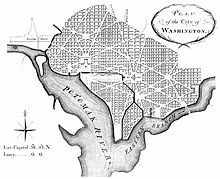

L'Enfant's "Plan of the city intended for the permanent seat of the government of the United States..." encompassed an area bounded by the Potomac River, the Eastern Branch, the base of the escarpment of the Atlantic Seaboard Fall Line, and Rock Creek.[21][27] His plan specified locations for the "Congress House" (the Capitol), which would be built on "Jenkins Hill" (later to be known as "Capitol Hill"), and the "President's House" (later after 1817, the White House), which would be situated on a ridge parallel to the Potomac River.[15][28] L'Enfant envisioned the "President's House" to have public gardens and monumental architecture. Reflecting his grandiose visions, he specified that the "President's House" would be five times the size of the building that was actually constructed.[16] Emphasizing the importance of the new Nation's Legislature, the "Congress House" would be located on a longitude designated as 0:0.[22][29][30][31]

The plan specified that most streets would be laid out in a grid. To form the grid, some streets would travel in an east-west direction, while others would travel in a north-south direction. Diagonal avenues, later named after the states of the Union, crossed the grid.[31][32][33] The diagonal avenues intersected with the north-south and east-west streets at circles and rectangular plazas that would later honor notable Americans and provide open space.

L'Enfant laid out a 400 feet (122 m)-wide garden-lined "grand avenue", which he expected to travel for about 1 mile (1.6 km) along an east-west axis in the center of an area that would later become the National Mall.[32] He also laid out a narrower avenue (Pennsylvania Avenue) which would connect the "Congress House" with the "President's House".[22][32] In time, Pennsylvania Avenue developed into the capital city's present "grand avenue".

Andrew Ellicott's 1792 revision of L'Enfant's plan of 1791–1792 for the "Federal City" later Washington City, District of Columbia

L'Enfant secured the lease of quarries at Wigginton Island and along Aquia Creek off the lower Potomac River in Virginia to supply Aquia Creek sandstone for the foundation and later for the wall slabs and blocks of the "Congress House" in November 1791.[34] However, his temperament and his insistence that his city design be realized as a whole, brought him into conflict with the Commissioners, who wanted to direct the limited funds available into construction of the Federal buildings. In this, they had the support of Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson.

During a contentious period in February 1792, Andrew Ellicott, who had been conducting the original boundary survey of the future District of Columbia (see: Boundary Stones (District of Columbia)) and the survey of the "Federal City" under the direction of the Commissioners, informed the Commissioners that L'Enfant had not been able to have the city plan engraved and had refused to provide him with the original plan (of which L'Enfant had prepared several versions).[35][36][37] Ellicott, with the aid of his brother, Benjamin Ellicott, then revised the plan, despite L'Enfant's protests.[35][36][37][38] Shortly thereafter, having along with Secretary Jefferson grown increasingly frustrated by L'Enfant's unresponsiveness and headstrong ways, President Washington dismissed the architect. After L'Enfant departed, Andrew Ellicott continued the city survey in accordance with the revised plan, several versions of which were engraved, published and distributed. As a result, Ellicott's revisions subsequently became the basis for the Capital City's development.[35][36][39][40][41][42]

L'Enfant was initially not paid for his work on his plan for the "Federal City". He fell into disgrace, spending much of the rest of his life trying to persuade Congress to pay him the tens of thousands of dollars that he claimed he was owed.[6] After a number of years, Congress finally paid him a small sum, nearly all of which went to his creditors.[4]

Later works

Morris' folly. Engraving from 1800 by William Russell Birch.

Death

L'Enfant died in poverty. He was buried at the Green Hill farm in Chillum, Prince George's County, Maryland. He left behind three watches, three compasses, some books, some maps, and surveying instruments, whose total value was about forty-five[46] dollars.[47]Legacy

In 1901 and 1902, the McMillan Commission used L'Enfant's plan as the cornerstone of a report that recommended a partial redesign of the capital city.[41] Among other things, the Commission's report laid out a plan for a sweeping mall in the area of L'Enfant's widest "grand avenue", which had not been constructed.At the instigation of a French Ambassador to the United States, Jean Jules Jusserand, L'Enfant's adopted nation then recognized his contributions. In 1909, after lying in state at the Capitol rotunda, L'Enfant's remains were re-interred in the Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia, in a slab tomb on a hill beneath the "Arlington House" (formerly the "Lee-Custis Mansion") overlooking the City by the Potomac that he had partially designed.[48][49] In 1911, L'Enfant was honored with a monument placed on top of his grave. Engraved on the monument is a portion of L'Enfant's own plan, which Andrew Ellicott's revision and the McMillan Commission's plan had superseded.[50]

Honors

- In 1942, an American cargo-carrying "Liberty" ship in World War II, named the S.S. "Pierre L'Enfant" was launched, part of a series of almost 2,000 ships mass-produced in an "assembly-line" fashion from eleven coastal shipyards. In 1970, she was shipwrecked and abandoned.

- L'Enfant Plaza, a complex of office buildings (with the headquarters of the United States Postal Service), a hotel, and an underground parking garage and a long series of underground corridors with a shopping center centered around an esplanade ('L'Enfant Promenade") in southwest Washington, D.C., was dedicated in 1968. Meeting rooms in the L'Enfant Plaza Hotel bear the names of French artists, military leaders, and explorers. The central portion of the plaza contains a map of the city. Within the city map is a smaller map that shows the plaza's location.

- Beneath the L'Enfant Plaza is one of the central rapid transit busy Metro stops in Washington, D.C., the L'Enfant Plaza station.

- In 1980, Western Plaza (subsequently renamed to Freedom Plaza) off Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W. in northwest downtown Washington, D.C., was designed. An inlay in the Plaza depicts parts of L'Enfant's architectural "Plan for the Federal City of Washington".[51][52]

- In 2003, L'Enfant's plan for Washington was commemorated on a USPS postage stamp.[53] The diamond shape of the stamp reflects the original 100 square miles (259 km2) tract of land selected for the District. Shown is a view along the National Mall, including the Capitol, the Washington Monument, and the Lincoln Memorial. Also portrayed are cherry blossoms around the "Tidal Basin" and row houses from the Shaw neighborhood.

- The Government of the District of Columbia has commissioned a statue of L'Enfant that it hopes will one day reside in the U.S. Capitol as part of the National Statuary Hall Collection centered in the old chamber of the Representatives. As Federal Law currently only allows U.S. states to contribute statues to the Collection, the District's Delegate to the U.S. House of Representatives, Eleanor Holmes Norton, is attempting to have the Congress change the law permit the installation of the statue in the Statuary Hall. The statue is presently displayed in a D.C. government office building.[54]

- Since 2005, the National Building Museum in Washington, D.C. has held an annual "L'Enfant Lecture on City Planning and Design" to draw attention to critical issues in city and regional planning in the United States.[55]

- The American Planning Association (APA) has created an award named in L'Enfant's honor which recognizes excellence in international planning.[56]

Notes

- Graham, Jed (July 21, 2006). "Pierre Charles L'Enfant, Major, United States Army". ArlingtonCemetery.net. Retrieved June 2, 2013.

Major, United States Army

- Morgan, p. 118

- L'Enfant identified himself as "Peter Charles L'Enfant" during most of his life while residing in the United States. (See: Bowling, 2002, and Sterling, 2003) He wrote this name on the last line of text in an oval in the upper left corner of his "Plan of the city intended for the permanent seat of the government of t(he) United States ...." (Washington, D.C.) and on other legal documents. During the early 1900s, a French ambassador to the U.S., Jean Jules Jusserand, popularized the use of L'Enfant's birth name, "Pierre Charles L'Enfant". (See: Bowling (2002).) The National Park Service has identified L'Enfant as "Major Peter Charles L'Enfant" and as "Major Pierre (Peter) Charles L'Enfant" in its histories of the Washington Monument on its website. The United States Code states in 40 U.S.C. § 3309: "(a) In General.—The purposes of this chapter shall be carried out in the District of Columbia as nearly as may be practicable in harmony with the plan of Peter Charles L'Enfant."

- Sterling

- "History of the Mall: The 1791 L'Enfant Plan and the Mall". A Monument To Democracy. National Coalition to Save Our Mall. Archived from the original on 2014-03-04. Retrieved 2015-01-04.

We now know that L’Enfant called himself "Peter" and not Pierre.

- Claims of L'Enfant, Peter Charles: 1800-1810. Digested Summary and Alphabetical List of Private Claims which Have Been Presented to the House of Representatives from the First to the Thirty-first Congress: Exhibiting the Action of Congress on Each Claim, with References to the Journals, Reports, Bills, &c., Elucidating Its Progress 2 (Washington, D.C.: United States House of Representatives). 1853. p. 309. Retrieved 2015-01-03. At Google Books

- Morgan, p. 119

- Caemmerer (1950), p. 85

-

"Pierre-Charles L'Enfant". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913.

"Pierre-Charles L'Enfant". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913. - Holland Lodge No. 8 F&AM membership records

- de Ravel d’Esclapon, Pierre F. (March–April 2011). "The Masonic Career of Major Pierre Charles L'Enfant". The Scottish Rite Journal (Washington, D.C.: Supreme Council, 33°, Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite of Freemasonry of the Southern Jurisdiction): 10–12. ISSN 1076-8572. Retrieved 2011-12-27.

- Reps, John William (1965). "9. Planning the National Capital". [http://books.google.com/books?id=ES4m9SedVZkC The Making of Urban America]. Princeton University Press. pp. 240–242. ISBN 0-691-00618-0.

- "An ACT for establishing the Temporary and Permanent Seat of the Government of the United States". Library of Congress. Retrieved 2008-12-12.

- Ellis, Joseph J. (2002). "The Dinner". [http://books.google.com/books?id=lsPztgGkYYgC Founding Brothers: The Revolutionary Generation]. Vintage. pp. 50–52. ISBN 0-375-70524-4.

- Leach, Sara Amy; Barthold, Elizabeth (1994-07-20). "L'Enfant Plan of the City of Washington, District of Columbia". National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. United States Department of the Interior: National Park Service. Retrieved 2012-01-08.

- Seale, William (1986). The President's House, Volume 1. White House Historical Association. pp. 1–4.

- Stewart, p. 50

- Seale, William (1986). The President's House, Volume 1. White House Historical Association. p. 9.

- L'Enfant, P.C. (June 22, 1791). "To The President of the United States". Records of the Columbia Historical Society (Washington, D.C.: Columbia Historical Society (1899)) 2: 32–37. Retrieved 2011-12-28.

|chapter=ignored (help) - Stewart, p. 52

- Passanneau, Joseph R. (2004). Washington Through Two Centuries: A History in Maps and Images. New York: The Monacelli Press, Inc. pp. 14–16, 24–27. ISBN 1-58093-091-3.

- L'Enfant, P.C. (August 19, 1791). "To The President of the United States". Records of the Columbia Historical Society (Washington, D.C.: Columbia Historical Society (1899)) 2: 38–48. Retrieved 2011-12-28.

|chapter=ignored (help) - Pierre Charles L'Enfant's 1791 "Plan of the city intended for the permanent seat of the government ...." in official website of the Library of Congress Retrieved 2008-08-13. Note: The plan that this web page describes identifies the plan's author as "Peter Charles L'Enfant". The web page nevertheless identifies the author as "Pierre-Charles L'Enfant."

- "The L'Enfant Plan". A Monument To Democracy: History of the Mall: The 1791 L'Enfant Plan and the Mall. National Coalition to Save Our Mall. Retrieved 2012-01-08.

- L'Enfant's Dotted line map of Washington, D.C., 1791, before Aug. 19th. in official website of the Library of Congress. Retrieved 2009-09-30.

- "A Washington DC Map Chronology". http://dcsymbols.com dcsymbols.com. Retrieved 2009-09-30.

- Faethz, E.F.M.; Pratt, F.W. (1874). "Sketch of Washington in embryo, viz: Previous to its survey by Major L'Enfant: Compiled from the rare historical researches of Dr. Joseph M. Toner … combined with the skill of S.R. Seibert C.E.". Map in the collection of the Library of Congress. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 2012-04-03.

- Vlach, John Michael (Spring 2004). "The Mysterious Mr. Jenkins of Jenkins Hill". United States Capitol Historical Society. Retrieved 2009-09-14.

- Federal Writers' Project (1937). Washington, City and Capital: Federal Writers' Project. Works Progress Administration / United States Government Printing Office. p. 210.

- L'Enfant, Peter Charles (1791). "Plan of the city intended for the permanent seat of the government of t(he) United States : projected agreeable to the direction of the President of the United States, in pursuance of an act of Congress passed the sixteenth day of July, MDCCXC, "establishing the permanent seat on the bank of the Potowmac": (Washington, D.C.)". American Memory. Library of Congress. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

- Moore, Charles (ed) (1902), "Fig. No. 61 -- L'Enfant Map of Washington (1791)", The Improvement Of The Park System Of The District of Columbia: Report by the United States Congress: Senate Committee on the District of Columbia and District of Columbia Park Commission, Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, p. 12, Fifty-Seventh Congress, First Session, Senate Report No. 166

- High resolution image of central portion of "The L'Enfant Plan for Washington" in Library of Congress, with transcribed excerpts of key to map and enlarged image in official website of the U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved 2009-10-23.

- Freedom Plaza in downtown D.C. contains an inlay of the central portion of L'Enfant's plan, an inlay of an oval that gives the title of the plan and the name of its author (identified as "Peter Charles L'Enfant") and inlays of the plan's legends. The coordinates of the inlay of the plan and its legends are: 38.8958437°N 77.0306772°W. The coordinates of the name "Peter Charles L'Enfant" are: 38.8958374°N 77.031215°W

- Morgan, p. 120

- Tindall, William (1914). "IV. The First Board of Commissioners". Standard History of the City of Washington From a Study of the Original Sources. Knoxville, Tennessee: H. W. Crew and Company. pp. 148–149.

- Stewart, John (1898). "Early Maps and Surveyors of the City of Washington, D.C". Records of the Columbia Historical Society 2: 55–56. Retrieved 2011-12-27.

- Ellicott, Andrew (February 23, 1792). "To Thomas Johnson, Daniel Carroll and David Stuart, Esqs." In Arnebeck, Bob. "Ellicott's letter to the commissioners on engraving the plan of the city, in which no reference is made to Banneker". The General and the Plan. Bob Arnebeck's Web Pages. Retrieved 2010-08-30.

- Kite, from L'Enfant and Washington" in website of Grand Lodge of British Columbia and Yukon, Ancient Free and Accepted Masons (Freemasons). Retrieved January 11, 2009.

- Bowling, Kenneth R. (1988). Creating the Federal city, 1774–1800: Potomac Fever. Washington, D.C.: American Institute of Architects Press.

- Bryan, W.B. (1899). "Something About L'Enfant And His Personal Affairs". Records of the Columbia Historical Society 2: p. 113.

- The L'Enfant and McMillan Plans in "Washington, D.C., A National Register of Historic Places Travel Inventory" in official website of the U.S. National Park Service Accessed August 14, 2008.

- Washington Map Society: Plan of the City of Washington. The U.S. National Archives holds a copy of "Ellicott's engraved Plan superimposed on the Plan of L'Enfant showing the changes made in the engraved Plan under the direction of President Washington". See "Scope & Contents" page of "Archival Description" for National Archives holding of "Miscellaneous Oversize Prints, Drawings and Posters of Projects Associated with the Commission of Fine Arts, compiled 1893–1950", ARC Identifier 518229/Local Identifier 66-M; Series from Record Group 66: Records of the Commission of Fine Arts, 1893–1981. Record of holding obtained through search in Archival Descriptions Search of ARC — Archival Research Catalog using search term L'Enfant Plan Ellicott, 2008-08-22.

- Jusserand, p. 184.

- Jusserand, pp. 185-186.

- History of Fort Washington Park, Maryland in official website of U.S. National Park Service Retrieved 2008-12-03.

- Grand Avenues by Scott W. Berg

- Jusserand, p. 190.

- Maj. L'Enfant's Forgotten Grave," by T. Loftin Snell, The Washington Post, Jul 30, 1950, pg. B3.

- Coordinates of grave site of Peter Charles L'Enfant in Arlington National Cemetery: 38.881093°N 77.072313°W

- Arlington National Cemetery: Historical Information: Pierre Charles L'Enfant

- Miller, Richard E. (April 15, 2009). "Freedom Plaza Marker". Historical Marker Database. Retrieved 2010-11-22.

- Busch, Richard T.; Smith, Kathryn Schneider, "W.7: Freedom Plaza: 13th and E Sts NW", Civil War to Civil Rights Downtown Heritage Trail, Washington, DC: Cultural Tourism DC, retrieved 2010-10-22

- "usps.gov — Nation's Capital celebrated on new commemorative postage stamp". Retrieved 2009-01-13.

- Ackland, Matt (2011-12-27). "DC Seeking To Have Statues Displayed Inside US Capitol". Washington, D.C.: MYFOXdc.com. Retrieved 2012-01-08.

- "L'Enfant Lecture on City Planning and Design". Adult Programs. National Building Museum. Retrieved 2012-01-08.

- National Planning Awards 2014 at American Planning Association site

References

- Berg, Scott W. (2007). Grand Avenues: The Story of the French Visionary Who Designed Washington, D.C. Pantheon Books. ISBN 978-0-375-42280-5. OCLC 70267127.

- Bowling, Kenneth R. (2002). Peter Charles L'Enfant: vision, honor, and male friendship in the early American Republic. Washington, D.C.: George Washington University. OCLC 51037796.

-

- Sterling, Christopher H. (2003). Revisiting an Old Controversy. Review of Bowling, Kenneth R. (2002), Peter Charles L'Enfant: vision, honor, and male friendship in the early American Republic. H-DC, H-Net Reviews. In H-Net Reviews of the Humanities and Social Sciences in website of H-Net Humanities and Social Sciences Online by The Center for Humane Arts, Letters, and Social Sciences Online, Michigan State University. Retrieved August 20, 2009.

- Caemmerer, H. Paul (1970). The Life of Pierre Charles L'Enfant. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0306713810. OCLC 99500.

- Jusserand, Jean Jules (1916). Major L'Enfant and the Federal City. With Americans of Past and Present Days (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons). pp. 137–195. OCLC 1075914.

- Kite, Elizabeth Sarah (1929). L'Enfant and Washington, 1791–1792. Johns Hopkins University Press. OCLC 2898164.

- Morgan, James Dudley, M.D. (1899). "Maj. Pierre Charles L'Enfant, The Unhonored and Unrewarded Engineer". Records of the Columbia Historical Society (Washington, D.C.: Columbia Historical Society). 2: 118–157. Retrieved 2011-08-15.

- Stewart, John (1899). "Early Maps and Surveyors of the City of Washington, D.C.". Records of the Columbia Historical Society (Washington, D.C.: Columbia Historical Society) 2: 48–71. Retrieved 2011-08-15.

- Worthington, Glen (2005-05-01). "The Vision of Pierre L’Enfant: A City to Inspire, A Plan to Preserve". Georgetown Law Historic Preservation Papers Series. Paper 9. Retrieved 2011-09-02.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pierre Charles L'Enfant. |

- Ovason, David, The Secret Architectpre of Our Nation's Capital: the Masons and the building of Washington, D.C., New York City: Perennial, 2002. ISBN 0-06-019537-1 ISBN 978-0060195373

- Mann, Nicholas, The Sacred Geometry of Washington, D.C.: The Integrity and Power of the Original Design, Green Magic 2006. ISBN 0-9547230-7-4, ISBN 978-0-9547230-7-1

No comments:

Post a Comment