L'Enfant laid out a 400 feet (122 m)-wide garden-lined "grand avenue", which he expected to travel for about 1 mile (1.6 km) along an east-west axis in the center of an area that would later become the National Mall.[32] He also laid out a narrower avenue (Pennsylvania Avenue) which would connect the "Congress House" with the "President's House".[22][32] In time, Pennsylvania Avenue developed into the capital city's present "grand avenue".

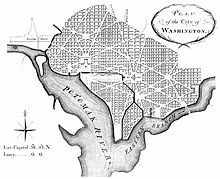

Andrew Ellicott's 1792 revision of L'Enfant's plan of 1791–1792 for the "Federal City" later Washington City, District of Columbia

L'Enfant secured the lease of quarries at Wigginton Island and along Aquia Creek off the lower Potomac River in Virginia to supply Aquia Creek sandstone for the foundation and later for the wall slabs and blocks of the "Congress House" in November 1791.[34] However, his temperament and his insistence that his city design be realized as a whole, brought him into conflict with the Commissioners, who wanted to direct the limited funds available into construction of the Federal buildings. In this, they had the support of Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson.

During a contentious period in February 1792, Andrew Ellicott, who had been conducting the original boundary survey of the future District of Columbia (see: Boundary Stones (District of Columbia)) and the survey of the "Federal City" under the direction of the Commissioners, informed the Commissioners that L'Enfant had not been able to have the city plan engraved and had refused to provide him with the original plan (of which L'Enfant had prepared several versions).[35][36][37] Ellicott, with the aid of his brother, Benjamin Ellicott, then revised the plan, despite L'Enfant's protests.[35][36][37][38] Shortly thereafter, having along with Secretary Jefferson grown increasingly frustrated by L'Enfant's unresponsiveness and headstrong ways, President Washington dismissed the architect. After L'Enfant departed, Andrew Ellicott continued the city survey in accordance with the revised plan, several versions of which were engraved, published and distributed. As a result, Ellicott's revisions subsequently became the basis for the Capital City's development.[35][36][39][40][41][42]

L'Enfant was initially not paid for his work on his plan for the "Federal City". He fell into disgrace, spending much of the rest of his life trying to persuade Congress to pay him the tens of thousands of dollars that he claimed he was owed.[6] After a number of years, Congress finally paid him a small sum, nearly all of which went to his creditors.[4]

Later works

Morris' folly. Engraving from 1800 by William Russell Birch.

Death

L'Enfant died in poverty. He was buried at the Green Hill farm in Chillum, Prince George's County, Maryland. He left behind three watches, three compasses, some books, some maps, and surveying instruments, whose total value was about forty-five[46] dollars.[47]

No comments:

Post a Comment