King Philip's War

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

King Philip's War, sometimes called the First Indian War, Metacom's War, Metacomet's War, or Metacom's Rebellion,[1] was an armed conflict between Native American inhabitants of present-day New England and English colonists and their Native American allies in 1675–78. The war is named for the main leader of the Native American side, Metacomet, known to the English as "King Philip".[2] The war continued in the most northern reaches of New England until the signing of the Treaty of Casco Bay in April 1678.[3]

Metacom (c. 1638-1676) was the second son of Wampanoag chief Massasoit, who had coexisted peacefully with the Pilgrims. Metacom succeeded his father in 1662 and reacted against the European settlers' continued encroaching onto Wampanoag lands. At Taunton in 1671, he was humiliated when colonists forced him to sign a new peace agreement that included the surrender of Indian guns. When officials in Plymouth Colony hanged three Wampanoags in 1675 for the murder of a Christianized Indian, Metacom's alliance launched a united assault on colonial towns throughout the region. Metacom's forces enjoyed initial victories in the first year, but then the Native American alliance began to unravel. By the end of the conflict, the Wampanoags and their Narragansett allies were almost completely destroyed. Metacom anticipated their defeat and returned to his ancestral home at Mt. Hope, where he was killed in battle.

The war was the single greatest calamity to occur in seventeenth-century Puritan New England and is considered by many to be the deadliest war in American history.[4] In proportion to the population, the resulting war was one of the bloodiest in American history. In the space of little more than a year, twelve of the region's towns were destroyed and many more damaged, the colony's economy was all but ruined, and its population was decimated, losing one-tenth of all men available for military service.[5][6] More than half of New England's towns were attacked by Native American warriors.[7]

King Philip's War began the development of a greater American identity, for the colonists' trials, without significant English government support, gave them a group identity separate and distinct from that of subjects of the king.[8]

Historical context[edit]

King Philip's War joined the Powhatan wars of 1610–14, 1622–32 and 1644–46[9] in Virginia, the Pequot War of 1637 in Connecticut, the Dutch-Indian war of 1643 along the Hudson River[10] and the Iroquois Beaver Wars of 1650[11] in a list of ongoing uprisings and conflicts between various Native American tribes and the French, Dutch, and English colonial settlements of Canada, New York, and New England.

Plymouth, Massachusetts, was established in 1620 with significant early help from local Native Americans, particularly Squanto and Massasoit, chief of the Wampanoag tribe. Subsequent colonists founded Salem, Boston, and many small towns aroundMassachusetts Bay between 1628 and 1640, at a time of increased English immigration. With a wave of immigration, and their building of towns such as Windsor, Connecticut (est. 1633), Hartford, Connecticut (est. 1636), Springfield, Massachusetts (est. 1636),Northampton, Massachusetts (est. 1654) and Providence, Rhode Island (est. 1636), the colonists progressively encroached on the traditional territories of the several Algonquian-speaking tribes in the region. Prior to King Philip's War, tensions fluctuated between tribes of Native Americans and the colonists, but relations were generally peaceful.[4]

Twenty thousand colonists settled in New England during the Great Migration. Colonial officials of the Rhode Island, Plymouth, Massachusetts Bay, Connecticut and the New Haven colonies each developed separate relations with the Wampanoag, Nipmuck,Narragansett, Mohegan, Pequot, and other tribes of New England, whose territories historically had differing boundaries. Many of the neighboring tribes had been traditional competitors and enemies. As the colonial population increased, the New Englanders expanded their settlements along the region's coastal plain and up the Connecticut River valley. By 1675 they had established a few small towns in the interior between Boston and the Connecticut River settlements.[citation needed]

The Wampanoag tribe, under Metacomet's leadership, had entered into an agreement with the Plymouth Colony and believed that they could rely on the colony for protection. However, in the decades preceding the war it became clear to them that the treaty did not protect them from English expansion, and land they had lost appeared to be given to rival Christian Indian tribes.[4]

Disease and war[edit]

Throughout the Northeast, the Native Americans had suffered severe population losses as a result of pandemics of smallpox, spotted fever, typhoid, and measles, infectious diseases carried by European fishermen, starting in about 1618, two years before the first colony at Plymouth had been settled.[12] Shifting alliances among the different Algonquian peoples, represented by leaders such as Massasoit, Sassacus, Uncas and Ninigret, and the colonial polities negotiated a troubled peace for several decades.[citation needed]

For almost half a century after the colonists' arrival, Massasoit of the Wampanoag had maintained an uneasy alliance with the English to benefit from their trade goods and as a counter-weight to his tribe's traditional enemies, the Pequot, Narragansett, and the Mohegan. Massasoit had to accept colonial incursion into Wampanoag territory as well as English political interference with his tribe.[citation needed] Maintaining good relations with the English became increasingly difficult, as the English colonists continued pressuring the Indians to sell land.[citation needed]

Failure of diplomacy[edit]

Metacomet became sachem of the Pokanoket and Grand Sachem of the Wampanoag Confederacy after the death in 1662 of his older brother, the Grand Sachem Wamsutta (called "Alexander" by the English). The latter had succeeded their father Massasoit (d. 1661) as chief. Well known to the English before his ascension as paramount chief to the Wampanoag, Metacomet distrusted the colonists. Wamsutta had been visiting theMarshfield home of Josiah Winslow, the governor of the Plymouth Colony, for peaceful negotiations, and became ill after being given a "portion of working physic" by a Doctor Fuller.

The Plymouth colonists had put in place laws making it illegal to do commerce with the Wampanoags. When they found out that Wamsutta had sold a parcel of land to Roger Williams, Josiah Winslow, the governor of the Plymouth Colony, had Wamsutta arrested even though Wampanoags that lived outside of colonist jurisdiction were not accountable to Plymouth Colony laws. Wamsutta's wife, Weetamoe, attempted to bring the chief back to Pokanoket. However, on the Taunton River the party saw that the end was near, and after beaching their canoes, Wamsutta died under an oak tree within viewing distance of Mount Hope.[13]

Metacomet began negotiating with the other Algonquian tribes against the Plymouth Colony soon after the deaths of his father Massasoit and his brother Wamsutta. His action was a reaction to the colonists' refusal to stop buying land and establishment of new settlements, combined with Wamsutta / Alexander's suspicious death.[13]

Population[edit]

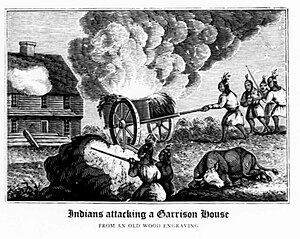

The population of New England immigrants from Europe totaled about 80,000 people. They lived in 110 towns, of which 64 were in the Massachusetts Colony, which then included the southwestern portion of the present state of Maine. The towns had about 16,000 men of military age who were almost all part of the militia—universal training was prevalent in all colonial New England towns. Many towns had built strong garrison houses for defense, and others had stockades enclosing most of the houses. All of these were strengthened as the war progressed. Some poorly populated towns without enough men to defend them were abandoned. Each town had local militias, based on all eligible men, who had to supply their own arms. Only those who were too old, too young, disabled, or clergy were excused from military service. The militias were usually only minimally trained and initially did relatively poorly against the warring Indians until more effective training and tactics could be devised. Joint forces of militia volunteers and volunteer Indian allies were found to be the most effective. The officers were usually elected by popular vote of the militia members.[citation needed] The Indian allies of the colonists—the Mohegans and Praying Indians—numbered about 1,000, with about 200 warriors.[14]

By 1676, the regional Native American population had decreased to about 10,000 Indians (exact numbers are unavailable), largely because of epidemics. These included about 4,000 Narragansett of western Rhode Island and eastern Connecticut; 2,400 Nipmuck of central and western Massachusetts; and 2,400 combined in the Massachusett and Pawtucket tribes, living about Massachusetts Bay and extending northwest to Maine. The Wampanoag and Pokanoket of Plymouth and eastern Rhode Island are thought to have numbered fewer than 1,000. About one in four were considered to be warriors. By then the Indians had almost universally adopted steel knives, tomahawks, and flintlock muskets as their weapons of choice. The various tribes had no common government. They had distinct cultures and often warred among themselves.[15] Despite different cultures they each spoke a version of the Algonquian language family.

The trial[edit]

John Sassamon, a Native American convert to Christianity, a so-called "praying Indian", played a key role as a "cultural mediator", negotiating with both sides while belonging to neither.[16] An early graduate of Harvard College, he served as a translator and adviser to Metacomet. He reported to the governor of Plymouth Colony that Metacomet planned to gather allies for Native American attacks on widely dispersed colonial settlements.[17]

Metacomet was brought before a public court, where court officials admitted they had no proof, but warned that if they had any further reports against him they would confiscate Wampanoag land and guns.[citation needed] Not long after, Sassamon's body was found in the ice-covered Assawompset Pond. Whether his death was the result of accident, suicide or murder was disputed at the time and since.[citation needed] Plymouth Colony officials arrested three Wampanoag, including one of Metacomet's counselors. On the testimony of a Native American, a jury that included six Indian elders convicted the men of Sassamon's murder. They were executed by hanging on June 8, 1675 (O.S.), at Plymouth. Some Wampanoag believed that both the trial and the court's sentence infringed on Wampanoag sovereignty.[citation needed]

Southern theatre, 1675[edit]

Raid on Swansea[edit]

In response to the trial and executions, on June 20, 1675 (O.S.) a band of Pokanoket attacked several isolated homesteads in the small Plymouth colony settlement of Swansea.[18] Laying siege to the town, they destroyed it five days later and killed several people. On June 27, 1675 (O.S.) (July 7, 1675 N.S.; See Old Style and New Style dates), a full eclipse of the moon occurred in the New England area.[19] Various tribes in New England looked at it as a good omen for attacking the colonists.[20] Officials from the Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay colonies responded quickly to the attacks on Swansea; on June 28 they sent a punitive military expedition that destroyed the Wampanoag town at Mount Hope (modern Bristol, Rhode Island).

The war quickly spread, and soon involved the Podunk and Nipmuck tribes. During the summer of 1675, the Native Americans attacked at Middleborough and Dartmouth (July 8), Mendon (July 14), Brookfield (August 2), and Lancaster (August 9). In early September they attacked Deerfield, Hadley, and Northfield (possibly giving rise to the Angel of Hadley legend).

Siege of Brookfield[edit]

Wheeler's Surprise, and the ensuing Siege of Brookfield, was a battle between Nipmuc Indians under Muttawmp, and the English of the Massachusetts Bay Colony under the command of Thomas Wheeler and Captain Edward Hutchinson, in August 1675.[21] The battle consisted of an initial ambush by the Nipmucs on Wheeler's unsuspecting party, followed by an attack on Brookfield, Massachusetts, and the consequent besieging of the remains of the colonial force. While the place where the siege part of the battle took place has always been known (at Ayers' Garrison in West Brookfield), the location of the initial ambush was a subject of extensive controversy among historians in the late nineteenth century.[22]

The New England Confederation, comprising the Massachusetts Bay Colony, Plymouth Colony, New Haven Colony and Connecticut Colony, declared war on the Native Americans on September 9, 1675. The Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, settled mostly by Puritan dissidents, tried to remain mostly neutral, but like the Narragansett they were dragged inexorably into the conflict. The next colonial expedition was to recover crops from abandoned fields along the Connecticut River for the coming winter and included almost 100 farmers/militia plus teamsters to drive the wagons.

Battle of Bloody Brook[edit]

The Battle of Bloody Brook was fought on September 12, 1675, between English colonial militia from the Massachusetts Bay Colony and a band of Indians led by the Nipmuc sachem Muttawmp. The Indians ambushed colonists escorting a train of wagons carrying the harvest from Deerfield to Hadley. They killed at least 40 militia men and 17 teamsters out of a company that included 79 militia.[23][24]

Attack on Springfield[edit]

The Indians next attacked on October 5, 1675, against the Connecticut River's largest settlement at the time, Springfield, Massachusetts. They burned to the ground nearly all of Springfield's buildings, including the town's grist mill. Most of the Springfielders who escaped unharmed took cover at the house of Miles Morgan, a resident who had constructed one of Springfield's few fortified blockhouses.[25] An Indian servant who worked for Morgan managed to escape and later alerted the Massachusetts Bay troops under the command of Major Samuel Appleton, who broke through to Springfield and drove off the attackers. Morgan's sons were famous Indian fighters in the territory. His son Peletiah was killed by Indians in 1675. Springfielders later honored Miles Morgan with a large statue in Court Square.[25]

The Great Swamp Fight[edit]

Main article: Great Swamp Fight

On November 2, Plymouth Colony governor Josiah Winslow led a combined force of colonial militia against the Narragansett tribe. The Narragansett had not been directly involved in the war, but they had sheltered many of the Wampanoag women and children. Several of their warriors were reported in several Indian raiding parties. The colonists distrusted the tribe and did not understand the various alliances. As the colonial forces went through Rhode Island, they found and burned several Indian towns which had been abandoned by the Narragansett, who had retreated to a massive fort in a frozen swamp. The cold weather in December froze the swamp so it was relatively easy to traverse. Led by a guide, "Indian Peter", on a very cold December 16, 1675, the colonial force found the Narragansett fort near present-day South Kingstown, Rhode Island. A combined force of Plymouth, Massachusetts, and Connecticut militia numbering about 1,000 men, including about 150 Pequots and Mohican Indian allies, attacked the Indian fort. The fierce battle that followed is known as the Great Swamp Fight. It is believed that the militia killed about 300 Narragansett. The militia burned the fort (occupying over 5 acres (20,000 m2) of land) and destroyed most of the tribe's winter stores.

Most of the Narragansett warriors and their families escaped into the frozen swamp. Facing a winter with little food and shelter, the entire surviving Narragansett tribe was forced out of quasi-neutrality and joined the fight. The colonists lost many of their officers in this assault: about 70 of their men were killed and nearly 150 more wounded. Lacking supplies for an extended campaign the rest of the colonial assembled forces returned to their homes. The nearby towns in Rhode Island provided care for the wounded until they could return to their homes.[26]

Native American campaign[edit]

Throughout the winter of 1675–76, Native Americans attacked and destroyed more frontier settlements in their effort to expel the English colonists. Attacks were made at Andover, Bridgewater, Chelmsford, Groton, Lancaster, Marlborough, Medfield, Medford, Millis,Portland, Providence, Rehoboth, Scituate, Seekonk, Simsbury, Sudbury, Suffield, Warwick, Weymouth, and Wrentham, including what is modern-day Plainville. The famous account written and published by Mary Rowlandson after the war gives a colonial captive's perspective on the conflict.[27]

Southern theatre, 1676[edit]

Lancaster raid[edit]

The Lancaster raid in February 1676 was an attack on the frontier community of Lancaster, Massachusetts, by Metacom. Metacom led a force of 1,500 Wampanoag, Nipmuc, and Narragansett Indians in a dawn attack on the isolated village (which then included all or part of the neighboring modern communities of Bolton and Clinton). They attacked five fortified houses. The house of the minister, Rev. Joseph Rowlandson, was set on fire, and most of its occupants (more than 30 people) were slaughtered. Rowlandson's wifeMary was taken prisoner, and afterward wrote a best-selling captivity narrative of her experiences. Many of the community's other houses were destroyed before the Indians retreated northward.

Plymouth Plantation Campaign[edit]

The spring of 1676 marked the high point for the combined tribes when, on March 12, they attacked Plymouth Plantation. Though the town withstood the assault, the natives had demonstrated their ability to penetrate deep into colonial territory. They attacked three more settlements: Longmeadow (near Springfield), Marlborough, and Simsbury were attacked two weeks later. They killed Captain Pierce[28] and a company of Massachusetts soldiers between Pawtucket and the Blackstone's settlement. Several colonial men were allegedly tortured and buried at Nine Men's Misery in Cumberland, as part of the Native Americans' ritual treatment of enemies. The natives burned the abandoned capital of Providence to the ground on March 29. At the same time, a small band of Native Americans infiltrated and burned part of Springfield while the militia was away.

The few hundred colonists of Rhode Island became an island colony for a time as their capital at Providence was sacked and burned and the colonists were driven back to Newport and Portsmouth on Aquidneck Island. The Connecticut River towns with their thousands of acres of cultivated crop land, known as the bread basket of New England, had to manage their crops by limiting their crop lands and working in large armed groups for self-protection.[29]:20 Towns such as Springfield, Hatfield, Hadley and Northampton, Massachusetts, fortified their towns, reinforced their militias and held their ground, though attacked several times. The small towns ofNorthfield and Deerfield, Massachusetts, and several other small towns, were abandoned as the surviving settlers retreated to the larger towns. The towns of the Connecticut colony escaped largely unharmed in the war, although more than 100 Connecticut militia died in their support of the other colonies.

Colonial and Mohawk Campaigns[edit]

The New York Mohawks—an Iroquois tribe, traditional enemies of many of the warring tribes—proceeded to raid isolated groups of Native Americans in Massachusetts, scattering and killing many. Traditional Indian crop-growing areas and fishing places in Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Connecticut were continually attacked by roving New England patrols of combined Colonials and their Native American allies. When found, any Indian crops were destroyed. The Indian tribes had poor luck finding any place to grow enough food or harvest enough migrating fish for the coming winter. Many of the warring Native American tribes drifted north into Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont and Canada. Some drifted west into New York and points farther west to avoid their traditional enemies, the Iroquois.

Attack on Sudbury[edit]

The Attack on Sudbury (April 21, 1676) was fought in Sudbury, Massachusetts. The town was surprised by Indian raiders at dawn, but security precautions limited the damage to unoccupied homesteads. Reinforcements that arrived from nearby towns were drawn into ambushes by the Indians; Captain Samuel Wadsworth lost his life and half of a 60-man militia in such an ambush. Afterwards, Indians made their way through much of Sudbury, but were held off by John Grout and a handful of men until colonial reinforcements arrived to help in the defense.

By April 1676 the Narragansett were defeated and their chief, Canonchet, was killed.

Battle of Turner's Falls[edit]

At the Battle of Turner's Falls, on May 18, 1676, Captain William Turner of the Massachusetts Militia and a group of about 150 militia volunteers (mostly minimally trained farmers) attacked a large fishing camp of Native Americans at Peskeopscut on the Connecticut River (now called Turners Falls, Massachusetts). The colonists claimed they killed 100–200 Native Americans in retaliation for earlier Indian attacks against Deerfield and other colonist settlements and the colonial losses in the Battle of Bloody Brook. Turner and nearly 40 of the militia were killed during the return from the falls.[30]

With the help of their long-time allies the Mohegans, the colonists defeated an attack at Hadley on June 12, 1676, and scattered most of the Indian survivors into New Hampshire and points farther north. Later that month, a force of 250 Native Americans was routed near Marlborough, Massachusetts. Other forces, often a combined force of colonial volunteers and their Indian allies, continued to attack, kill, capture or disperse bands of Narragansett, Nipmuc, Wampanough, etc. as they tried to plant crops or return to their traditional locations. The colonists granted amnesty to Native Americans from the tribes who surrendered or were captured and showed they had not participated in the conflict. The captured Indian participants whom they knew had participated in attacks on the many settlements were hanged or shipped off to slavery in Bermuda.

No comments:

Post a Comment