Pequot War

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Pequot War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

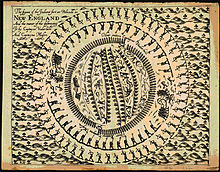

A 19th-century engraving depicting an incident in the Pequot War | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Pequot tribe | English Colonists

Native American Allies

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Sachem Sassacus | Henry Vane the Younger John Winthrop Sachem Uncas Sagamore Wequash Sachem Miantonomoh | ||||||

The Pequot War was an armed conflict between the Pequot tribe and an alliance of the English colonists of the Massachusetts Bay, Plymouth, and Saybrook colonies and their Native American allies (theNarragansett and Mohegan tribes) which occurred between 1634 and 1638. The Pequots lost the war. At the end, about seven hundred Pequots had been killed or taken into captivity.[1] Hundreds of prisoners were sold into slavery to the West Indies.[2] Other survivors were dispersed. The result was the elimination of the Pequot as a viable polity in what is present-day Southern New England.

It would take the Pequot more than three and a half centuries to regain political and economic power in their traditional homeland along the Pequot (present-day Thames) and Mystic rivers in what is now southeastern Connecticut.[3]

Etymology[edit]

The name Pequot is a Mohegan term, the meaning of which is in dispute among Algonquian-language specialists. Most recent sources in claiming that "Pequot" comes from Paquatauoq, (the destroyers), rely on the speculations of an early 20th-century authority on Algonquian languages, Frank Speck; an anthropologist and specialist of Pequot-Mohegan in the 1920s-1930s, he had doubts about this etymology. He believed that another term, translated as relating to the "shallowness of a body of water", seemed more plausible.[4]

Origins[edit]

The Pequot and their traditional enemies, the Mohegan, were at one time a single sociopolitical entity. Anthropologists and historians contend that sometime before contact with the Puritan English, they split into the two competing groups.[5] The earliest historians of the Pequot War speculated that the Pequot migrated from the upper Hudson River Valley toward central and eastern Connecticut sometime around 1500. These claims are disputed by the evidence of modern archeology and anthropology finds.[6]

In the 1630s, the Connecticut River Valley was in turmoil. The Pequot aggressively worked to extend their area of control, at the expense of the Wampanoag to the north, the Narragansett to the east, the Connecticut River Valley Algonquians and Mohegan to the west, and the Algonquian people of present-day Long Island to the south. The tribes contended for political dominance and control of the European fur trade. A series of smallpox epidemics over the course of the previous three decades had severely reduced the Native American populations due to their lack of immunity to the disease.[7] As a result, there was a power vacuum in the area.

The Dutch and the English, from Western Europe, across the Atlantic Ocean, were also striving to extend the reach of their trade into the interior to achieve dominance in the lush, fertile region. The colonies were new at the time, the original settlements having been founded in the 1620s. By 1636, the Dutch had fortified their trading post, and the English had built a trading fort at Saybrook. English Puritans from Massachusetts Bay and Plymouth colonies settled at the then four recently established river towns of Windsor (1632,)Wethersfield (1633,), Hartford (1635) and Springfield (1636.)

Belligerents[edit]

- Pequot: Sachem Sassacus

- Eastern Niantic

- Western Niantic: Sachem Sassious

- Mohigg: Sachem Uncas

- Niantic Sagamore Wequash

- Narragansett: Sachem Miantonomo

- Montauk or (Montaukett).

- Massachusetts Bay Colony: Governors Henry Vane and John Winthrop, Captains John Underhill and John Endecott

- Plymouth Colony: Governors Edward Winslow and William Bradford, and Captain Myles Standish

- Connecticut Colony: Thomas Hooker, Captain John Mason, Robert Seeley, Lt. William Pratt (c. 1609-1670)

- Saybrook Colony: Lion Gardiner

Causes for war[edit]

Before the war's inception, efforts to control fur trade access resulted in a series of escalating incidents and attacks that increased tensions on both sides. Political divisions between the Pequot and Mohegan widened as they aligned with different trade sources—the Mohegan with the English, and the Pequot with the Dutch. The Pequot assaulted a tribe of Indians who had tried to trade at what is known as Hartford. Tension sparked as the Massachusetts Bay Colony, became a stronghold for wampum, the supply of which the Pequot had controlled up until 1633.[citation?] John Stone, an English rogue, smuggler and privateer, and about seven of his crew were murdered by the Western tributary clients of the Pequot, the Niantic. According to the Pequots' later explanations, they did that in reprisal for the Dutch having murdered the principal Pequot sachem Tatobem, and were unaware of the fact that Stone was English and not Dutch.[8] In the earlier incident, Tatobem had boarded a Dutch vessel to trade. Instead of conducting trade, the Dutch seized the sachem and appealed for a substantial amount of ransom for his safe return. The Pequot quickly sent bushels of wampum, but received only Tatobem's dead body in return.

Stone, the privateer, was from the West Indies. He had been banished from Boston for malfeasance (including drunkenness, adultery and piracy). Since he was known to have powerful connections in other colonies as well as London, he was expected to use them against the Boston colony. Setting sail from Boston, Stone abducted two Western Niantic men, forcing them to show him the way up the Connecticut River. Soon after, he and his crew were suddenly attacked and killed by a larger group of Western Niantic.[9] While the initial reactions in Boston varied between indifference and outright joy at Stone's death,[10] the colonial officials later decided to protest the killing. They did not accept the Pequots' excuses that they had been unaware of Stone's nationality. The Pequot sachem Sassacus sent some wampum to atone for the murders, but refused the colonists' demands that the Western Niantic warriors responsible for Stone's death be turned over to them for trial and punishment.[11]

On July 20, 1636, a respected trader named John Oldham was attacked on a trading voyage to Block Island. He and several of his crew were killed and his ship looted by Narragansett-allied Indians who sought to discourage English settlers from trading with their Pequot rivals. In the weeks that followed, colonial officials from Massachusetts Bay, Rhode Island, and Connecticut, assumed the Narragansett were the likely culprits. Knowing that the Indians of Block Island were allies of the Eastern Niantic, who were allied with the Narragansett, Puritan officials became suspicious of the Narragansett.[12] However, Narragansett leaders were able to convince the English that the perpetrators were being sheltered by the Pequots.

Battles[edit]

News of Oldham's death became the subject of sermons in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. In August, Governor Vane sent John Endecott to exact revenge on the Indians of Block Island. Endecott's party of roughly 90 men sailed to Block Island and attacked two apparently abandoned Niantic villages. Most of the Niantic escaped, while two of Endecott's men were injured. The English claimed to have killed 14, but later Narragansett reports claimed only one Indian was killed on the island. The Puritan militia burned the villages to the ground. They carried away crops which the Niantic had stored for winter, and destroyed what they could not carry. Endecott went on to Fort Saybrook.

The English at Saybrook were not happy about the raid, but agreed that some of them would accompany Endecott as guides. Endecott sailed along the coast to a Pequot village, where he repeated the previous year's demand of payment for the death of Stone and more for Oldham. After some discussion, Endecott concluded that the Pequot were stalling and attacked. The Pequot ruse had worked, and most escaped into the woods. Endecott had his forces burn down the village and crops before sailing home.

Pequot raids[edit]

In the aftermath, the English of Connecticut Colony had to deal with the anger of the Pequot. The Pequot attempted to get their allies, some 36 tributary villages, to join their cause but were only partly effective. The Western Niantic (Nehantic) joined them but the Eastern Niantic (Nehantic) remained neutral. The traditional enemies of the Pequot, the Mohegan and the Narragansett, openly sided with the English. The Narragansett had warred with and lost territory to the Pequot in 1622. Now their friend Roger Williams urged the Narragansett to side with the English against the Pequot.

Through the Autumn and winter, Fort Saybrook was effectively besieged. People who ventured outside were killed. As spring arrived in 1637, the Pequot stepped up their raids on Connecticut towns. On April 23, Wongunk chief Sequin attacked Wethersfield with Pequot help. They killed six men and three women, a number of cattle and horses, and took two young girls captive. (They were daughters of William Swaine and were later ransomed by Dutch traders.)[13][14][15] In all, the towns lost about 30 settlers.

In May, leaders of Connecticut river towns met in Hartford, raised a militia, and placed Captain John Mason in command. Mason set out with 90 militia and 70 Mohegan warriors under Uncas to punish the Pequot. At Fort Saybrook, Captain Mason was joined by John Underhill and another 20 men. Underhill and Mason sailed from Fort Saybrook to Narragansett Bay, a tactic intended to mislead Pequot spies along the shoreline into thinking the English were not intending an attack. After landing the troops on shore, Mason and Underhill marched their forces approximately twenty miles towards Fort Mystic (present-day Mystic) and led a surprise attack before dawn.

The Mystic massacre[edit]

Main article: Mystic massacre

Believing that the English had returned to Boston, the Pequot sachem Sassacus took several hundred of his warriors to make another raid on Hartford. Mason had visited and recruited the Narragansett, who joined him with several hundred warriors. Several allied Niantic warriors also joined Mason's group. On May 26, 1637, with a force up to about 400 fighting men, Mason attacked Misistuck by surprise. He estimated that "six or seven Hundred" Pequot were there when his forces assaulted the palisade. As some 150 warriors had accompanied Sassacus to Hartford, so the inhabitants remaining were largely Pequot women and children, and older men. Mason ordered that the enclosure be set on fire.

Justifying his conduct later, Mason declared that the attack against the Pequot was the act of a God who "laughed his Enemies and the Enemies of his People to scorn making [the Pequot] as a fiery Oven... Thus did the Lord judge among the Heathen, filling [Mystic] with dead Bodies."[16] Mason insisted that any Pequot attempting to escape the flames should be killed. Of the estimated 600 to 700 Pequot resident at Mystic that day, only seven survived to be taken prisoner, while another seven escaped to the woods.[17]

The Narragansett and Mohegan warriors with Mason and Underhill's colonial militia were horrified by the actions and "manner of the Englishmen's fight... because it is too furious, and slays too many men."[18][19] The Narragansett left the warfare and returned home.

Believing the mission accomplished, Mason set out for home. Becoming temporarily lost, his militia narrowly missed returning Pequot warriors. After seeing the destruction of Mystic, they gave chase to the English forces but to little avail.

War's end[edit]

The destruction of people and the village of Mystic broke the Pequot and deprived them of their allies. Forced to abandon their villages, the Pequot fled—mostly in small bands—to seek refuge with other southern Algonquian peoples. Many were hunted down by Mohegan and Narragansett warriors. The largest group, led by Sassacus, were denied aid by the Metoac (Montauk, or Montaukett) from present-day Long Island. Sassacus led roughly 400 warriors west along the coast toward the Dutch at New Amsterdam and their Native allies. When they crossed the Connecticut River, the Pequot killed three men whom they encountered near Fort Saybrook.

In mid-June, John Mason set out from Saybrook with 160 men and 40 Mohegan scouts led by Uncas. They caught up with the refugees at Sasqua, a Mattabesic village near present-day Fairfield, Connecticut. Surrounded in a nearby swamp, the Pequot refused to surrender. The English allowed several hundred, mostly women and children, to leave with the Mattabesic[citation needed]. In the ensuing battle, Sassacus broke free with perhaps 80 warriors, but 180 Pequot men were killed or captured. The colonists memorialized this event as the Great Swamp Fight, or Fairfield Swamp Fight in its modern interpretation.

Sassacus and his followers had hoped to gain refuge among the Mohawk in present-day New York. However, the Mohawk instead killed Sassacus and his warriors. They sent Sassacus' scalp to Hartford as a symbolic offering of Mohawk friendship with the Connecticut Colony. English colonial officials continued to call for hunting down what remained of the Pequot months after war's end.

No comments:

Post a Comment