He reminds me ...........in that aspect...............of Ervin Magic Johnson..........Isiah Thomas.........the older generation one.(others as well, but time is in short commodity)...........they both won in college and the NBA...............Magic even won state in high school I think...............and Olympic gold medals.............he won everywhere he played...............undeniably outstanding........which is why I liked Isiah T.........Magic J........and Bill Russell so much.............and they had good personalities...........and were good with the media.............you will never find a more class act than Bill Russell...........in any sport...........

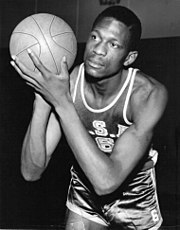

Bill Russell

basketball player. Russell played center for the Boston Celtics of the National Basketball Association (NBA) from 1956 to 1969. A five-time NBA Most Valuable Player and a twelve-time All-Star, he was the centerpiece of the Celtics dynasty, winning eleven NBA championships during his thirteen-year career. Russell holds the record for the most championships won by an athlete in a North American sports league (tied with Henri Richard of the National Hockey League). Before his professional career, Russell led the University of San Francisco to two consecutive NCAA championships in 1955 and 1956, and he captained the gold-medal winning U.S. national basketball team at the 1956 Summer Olympics.[1]

Russell is widely considered one of the best players in NBA history. He was 6 ft 10 in (2.08 m) tall, with a 7 ft 4 in (2.24 m) wingspan.[2][3] His shot-blocking and man-to-man defense were major reasons for the Celtics' domination of the NBA during his career. He also inspired his teammates to elevate their own defensive play. Russell was equally notable for his rebounding abilities. He led the NBA in rebounds four times, had a dozen consecutive seasons of 1,000 or more rebounds,[4] and remains second all-time in both total rebounds and rebounds per game. He is one of just two NBA players (the other being prominent rival Wilt Chamberlain) to have grabbed more than 50 rebounds in a game. Russell was never the focal point of the Celtics' offense, but he did score 14,522 career points and provided effective passing.

Russell played in the wake of pioneers like Earl Lloyd, Chuck Cooper, and Sweetwater Clifton, and he was the first African American player to achieve superstar status in the NBA. He also served a three-season (1966–69) stint as player-coach for the Celtics, becoming the first African-American coach in North American pro sports and the first to win a world championship. In 2011, Barack Obama awarded Russell the Presidential Medal of Freedom for his accomplishments on the court and in the Civil Rights Movement.[1]

Russell is one of seven players in history to win an NCAA Championship, an NBA Championship, and an Olympic gold medal.[5] He was inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame and the National Collegiate Basketball Hall of Fame. He was selected into the NBA 25th Anniversary Team in 1971 and the NBA 35th Anniversary Team in 1980, and named as one of the 50 Greatest Players in NBA History in 1996, one of only four players to receive all three honors. In 2007, he was enshrined in the FIBA Hall of Fame. In Russell's honor the NBA renamed the NBA Finals Most Valuable Player trophy in 2009: it is now the Bill Russell NBA Finals Most Valuable Player Award.

Charles Russell was described as a "stern, hard man" who initially worked in a paper factory as a janitor, which was a typical "Negro Job"—low paid and not intellectually challenging, as sports journalist John Taylor commented.[7] When World War II broke out, the elder Russell became a truck driver.[7] Russell was closer to his mother Katie than to his father,[7] and he received a major emotional blow when she suddenly died when he was 12 years old. His father gave up his trucking job and became a steelworker to be closer to his semi-orphaned children.[7] Russell has stated that his father became his childhood hero, later followed up by Minneapolis Lakers superstar George "Mr. Basketball" Mikan, who he met when he was in high school.[8] Mikan, in turn, would say of Russell the college basketball player, "Let's face it, he's the best ever. He's so good, he scares you."[9]

Future Baseball Hall-of-Famer Frank Robinson was one of Russell's high school basketball teammates.[14]

At USF, Russell became the new starting center for coach Phil Woolpert. Woolpert emphasized defense and deliberate half-court play, which were concepts that favored Russell's exceptional defensive skills.[16] Woolpert's choices of how to deploy his players were unaffected by issues of skin color. In 1954, he became the first coach of a major college basketball squad to start three African American players: Russell, K. C. Jones and Hal Perry.[17] In his USF years, Russell used his relative lack of bulk to develop a unique style of defense: instead of purely guarding the opposing center, he used his quickness and speed to play help defense against opposing forwards and aggressively challenge their shots.[16] Combining the stature and shot-blocking skills of a center with the foot speed of a guard, Russell became the centerpiece of a USF team that soon became a force in college basketball. After USF kept Holy Cross star Tom Heinsohn scoreless in an entire half, Sports Illustrated wrote, "If [Russell] ever learns to hit the basket, they're going to have to rewrite the rules."[16][18] The NCAA did in fact rewrite rules in response to Russell's dominant play; the lane was widened for his junior year. After he graduated, the NCAA rules committee instituted a second new rule to counter the play of big men like Russell; basket interference was now prohibited.[19] The NCAA pays close attention to college basketball superstars. Over the years, several rule changes have gone into effect to counter the dominant play of big men. Two good examples are goal-tending in response to George Mikan (1945) and prohibition of the dunk shot by Lew Alcindor (1967), althought that rule was eventually repealed.[20]

However, the games were often difficult for the USF squad. Russell and his African American teammates became targets of racist jeers, particularly on the road.[21] In one notable incident, hotels in Oklahoma City refused to admit Russell and his black teammates while they were in town for the 1954 All-College Tournament. In protest, the whole team decided to camp out in a closed college dorm, which was later called an important bonding experience for the group.[17] Decades later, Russell explained that his experiences hardened him against abuse of all kinds. "I never permitted myself to be a victim", he said.[22][23]

Racism also shaped his lifelong paradigm as a team player. "At that time", he has said, "it was never acceptable that a black player was the best. That did not happen ... My junior year in college, I had what I thought was the one of the best college seasons ever. We won 28 out of 29 games. We won the National Championship. I was the [Most Valuable Player] at the Final Four. I was first team All American. I averaged over 20 points and over 20 rebounds, and I was the only guy in college blocking shots. So after the season was over, they had a Northern California banquet, and they picked another center as Player of the Year in Northern California. Well, that let me know that if I were to accept these as the final judges of my career I would die a bitter old man." So he made a conscious decision, he said, to put the team first and foremost, and not worry about individual achievements.[24]

On the hardwood, his experiences were far more pleasant. Russell led USF to NCAA championships in 1955 and 1956, including a string of 55 consecutive victories. He became known for his strong defense and shot-blocking skills, once denying 13 shots in a game. UCLA coach John Wooden called Russell "the greatest defensive man I've ever seen".[17] During his college career, Russell averaged 20.7 points per game and 20.3 rebounds per game.[1]

Russell also competed in the 440 yards (402.3 m) race, which he could complete in 49.6 seconds.[30]

However, Boston's chances of getting Russell seemed slim. Because the Celtics had finished second in the previous season and the worst teams had the highest draft picks, the Celtics had slipped too low in the draft order to pick Russell. In addition, Auerbach had already used his territorial pick to acquire talented forward Tom Heinsohn. But Auerbach knew that the Rochester Royals, who owned the first draft pick, already had a skilled rebounder in Maurice Stokes, were looking for an outside shooting guard and were unwilling to pay Russell the $25,000 signing bonus he requested. Red Auerbach offered the Ice Capades if they didn’t draft Russell number one. Rochester got their ice show.[33] The St. Louis Hawks, who owned the second pick, drafted Russell, but were vying for Celtics center Ed Macauley, a six-time All-Star who had roots in St. Louis. Auerbach agreed to trade Macauley, who had previously asked to be traded to St. Louis in order to be with his sick son, if the Hawks gave up Russell. The owner of St Louis called Auerbach later and demanded more in the trade. Not only did he want Macauley, who was the Celtics premier player at the time, he wanted Cliff Hagan, who had been serving in the military for three years and had not yet played for the Celtics. After much debate, Auerbach agreed to give up Hagan, and the Hawks made the trade.[34]

During that same draft, Boston also drafted guard K. C. Jones, Russell's former USF teammate. Thus, in one night, the Celtics managed to draft three future Hall of Famers: Russell, Jones and Heinsohn.[1] The Russell draft-day trade was later called one of the most important trades in the history of North American sports.[33]

Russell is widely considered one of the best players in NBA history. He was 6 ft 10 in (2.08 m) tall, with a 7 ft 4 in (2.24 m) wingspan.[2][3] His shot-blocking and man-to-man defense were major reasons for the Celtics' domination of the NBA during his career. He also inspired his teammates to elevate their own defensive play. Russell was equally notable for his rebounding abilities. He led the NBA in rebounds four times, had a dozen consecutive seasons of 1,000 or more rebounds,[4] and remains second all-time in both total rebounds and rebounds per game. He is one of just two NBA players (the other being prominent rival Wilt Chamberlain) to have grabbed more than 50 rebounds in a game. Russell was never the focal point of the Celtics' offense, but he did score 14,522 career points and provided effective passing.

Russell played in the wake of pioneers like Earl Lloyd, Chuck Cooper, and Sweetwater Clifton, and he was the first African American player to achieve superstar status in the NBA. He also served a three-season (1966–69) stint as player-coach for the Celtics, becoming the first African-American coach in North American pro sports and the first to win a world championship. In 2011, Barack Obama awarded Russell the Presidential Medal of Freedom for his accomplishments on the court and in the Civil Rights Movement.[1]

Russell is one of seven players in history to win an NCAA Championship, an NBA Championship, and an Olympic gold medal.[5] He was inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame and the National Collegiate Basketball Hall of Fame. He was selected into the NBA 25th Anniversary Team in 1971 and the NBA 35th Anniversary Team in 1980, and named as one of the 50 Greatest Players in NBA History in 1996, one of only four players to receive all three honors. In 2007, he was enshrined in the FIBA Hall of Fame. In Russell's honor the NBA renamed the NBA Finals Most Valuable Player trophy in 2009: it is now the Bill Russell NBA Finals Most Valuable Player Award.

Contents

[hide]- 1 Early years

- 2 College years

- 3 1956 NBA draft

- 4 1956 Olympics

- 5 Professional career

- 6 Post-playing career

- 7 Head coaching record

- 8 Accomplishments and legacy

- 9 Personal life

- 10 Earnings

- 11 Personality

- 12 Russell–Chamberlain relations

- 13 Racist abuse, controversy, and relationship with Boston fans

- 14 Statue

- 15 See also

- 16 Selected publications

- 17 References

- 18 Further reading

- 19 External links

Early years[edit]

Family and personal life[edit]

Bill Russell was born to Charles Russell and Katie Russell in West Monroe, Louisiana. Like almost all southern towns and cities of that time, West Monroe was a highly segregated place, and the Russells often struggled with racism in their daily lives.[6] Russell's father was once refused service at a gas station until the staff had taken care of all the white customers. When his father attempted to leave and find a different station, the attendant stuck a shotgun in his face and threatened to kill him if he didn't stay and wait his turn.[6] In another incident, Russell's mother was walking outside in a fancy dress when a white policeman accosted her. He told her to go home and remove the dress, which he described as "white woman's clothing".[6] During World War II, large numbers of blacks were moving to the West to look for work there. When Russell was eight years old, his father moved the family out of Louisiana and settled in Oakland, California.[6] While there, the family fell into poverty, and Russell spent his childhood living in a series of public housing projects.[6]Charles Russell was described as a "stern, hard man" who initially worked in a paper factory as a janitor, which was a typical "Negro Job"—low paid and not intellectually challenging, as sports journalist John Taylor commented.[7] When World War II broke out, the elder Russell became a truck driver.[7] Russell was closer to his mother Katie than to his father,[7] and he received a major emotional blow when she suddenly died when he was 12 years old. His father gave up his trucking job and became a steelworker to be closer to his semi-orphaned children.[7] Russell has stated that his father became his childhood hero, later followed up by Minneapolis Lakers superstar George "Mr. Basketball" Mikan, who he met when he was in high school.[8] Mikan, in turn, would say of Russell the college basketball player, "Let's face it, he's the best ever. He's so good, he scares you."[9]

Initial exposure to basketball[edit]

In his early years, Russell struggled to develop his skills as a basketball player. Although Russell was a good runner and jumper and had large hands,[7] he simply did not understand the game and was cut from the team in junior high school. As a freshman at McClymonds High School[10] in Oakland, Russell was almost cut again.[11] However, coach George Powles saw Russell's raw athletic potential and encouraged him to work on his fundamentals.[7] Since Russell's previous experiences with white authority figures were often negative, he was delighted to receive warm words from his white coach. He worked hard and used the benefits of a growth spurt to become a decent basketball player, but it was not until his junior and senior years that he began to excel, winning back to back high school state championships.[11] Russell soon became noted for his unusual style of defense. He later recalled, "To play good defense ... it was told back then that you had to stay flatfooted at all times to react quickly. When I started to jump to make defensive plays and to block shots, I was initially corrected, but I stuck with it, and it paid off."[12] Russell, in an autobiographical account, notes while on a California High School All-Stars tour, he became obsessed with studying and memorizing other players’ moves (e.g., footwork such as which foot they moved first on which play) as preparation for defending against them, which including practicing in front of a mirror at night. Russell further described himself as an avid reader of Dell Magazines' 1950s sports publications, which he used to scout opponents' moves for the purpose of defending against them.[13]Future Baseball Hall-of-Famer Frank Robinson was one of Russell's high school basketball teammates.[14]

College years[edit]

Basketball[edit]

Due to his race, Russell was ignored by college recruiters and did not receive a single letter of intent until recruiter Hal DeJulio from the University of San Francisco (USF) watched him play in a high school game. DeJulio was not impressed by Russell's meager scoring and "atrocious fundamentals",[15] but sensed that the young center had an extraordinary instinct for the game, especially in the clutch.[15] When DeJulio offered Russell a scholarship, he eagerly accepted.[11] Sports journalist John Taylor described it as a watershed event in Russell's life, because Russell realized that basketball was his one chance to escape poverty and racism. As a consequence, Russell swore to make the best of it.[7]At USF, Russell became the new starting center for coach Phil Woolpert. Woolpert emphasized defense and deliberate half-court play, which were concepts that favored Russell's exceptional defensive skills.[16] Woolpert's choices of how to deploy his players were unaffected by issues of skin color. In 1954, he became the first coach of a major college basketball squad to start three African American players: Russell, K. C. Jones and Hal Perry.[17] In his USF years, Russell used his relative lack of bulk to develop a unique style of defense: instead of purely guarding the opposing center, he used his quickness and speed to play help defense against opposing forwards and aggressively challenge their shots.[16] Combining the stature and shot-blocking skills of a center with the foot speed of a guard, Russell became the centerpiece of a USF team that soon became a force in college basketball. After USF kept Holy Cross star Tom Heinsohn scoreless in an entire half, Sports Illustrated wrote, "If [Russell] ever learns to hit the basket, they're going to have to rewrite the rules."[16][18] The NCAA did in fact rewrite rules in response to Russell's dominant play; the lane was widened for his junior year. After he graduated, the NCAA rules committee instituted a second new rule to counter the play of big men like Russell; basket interference was now prohibited.[19] The NCAA pays close attention to college basketball superstars. Over the years, several rule changes have gone into effect to counter the dominant play of big men. Two good examples are goal-tending in response to George Mikan (1945) and prohibition of the dunk shot by Lew Alcindor (1967), althought that rule was eventually repealed.[20]

Racism also shaped his lifelong paradigm as a team player. "At that time", he has said, "it was never acceptable that a black player was the best. That did not happen ... My junior year in college, I had what I thought was the one of the best college seasons ever. We won 28 out of 29 games. We won the National Championship. I was the [Most Valuable Player] at the Final Four. I was first team All American. I averaged over 20 points and over 20 rebounds, and I was the only guy in college blocking shots. So after the season was over, they had a Northern California banquet, and they picked another center as Player of the Year in Northern California. Well, that let me know that if I were to accept these as the final judges of my career I would die a bitter old man." So he made a conscious decision, he said, to put the team first and foremost, and not worry about individual achievements.[24]

On the hardwood, his experiences were far more pleasant. Russell led USF to NCAA championships in 1955 and 1956, including a string of 55 consecutive victories. He became known for his strong defense and shot-blocking skills, once denying 13 shots in a game. UCLA coach John Wooden called Russell "the greatest defensive man I've ever seen".[17] During his college career, Russell averaged 20.7 points per game and 20.3 rebounds per game.[1]

Track and field[edit]

Besides basketball, Russell represented USF in track and field events. Russell was a standout in the high jump; he was ranked the seventh-best high-jumper in the world in 1956 (his graduation year) according to Track & Field News (this despite not competing in Olympic high-jump competition that year[8]).[25] That year, Russell won high jump titles at the Central California AAU meet, the Pacific AAU meet, and the West Coast Relays. One of his highest jumps occurred at the West Coast Relays, where he achieved a mark of 6 feet 9 1⁄4 inches (2.06 m);[26] at the meet Russell tied Charlie Dumas, who would later in the year both win gold in the Melbourne Olympics for the United States and become the first human to high-jump 7 feet (2.13 m).[27] Like fellow world-class high-jumpers of that era, Russell did not use the Fosbury Flop high-jump technique with which all high jump world records after 1978 have been set.[28][29]Russell also competed in the 440 yards (402.3 m) race, which he could complete in 49.6 seconds.[30]

Plans for a professional basketball career after college[edit]

The Harlem Globetrotters invited Russell to join their exhibition basketball squad. Russell, who was sensitive to any racial prejudice, was enraged by the fact that owner Abe Saperstein would only discuss the matter with Woolpert. While Saperstein spoke to Woolpert in a meeting, Globetrotters assistant coach Harry Hanna tried to entertain Russell with jokes. The USF center was livid after this snub and declined the offer: he reasoned that if Saperstein was too smart to speak with him, then he was too smart to play for Saperstein. Instead, Russell made himself eligible for the 1956 NBA draft.[31]1956 NBA draft[edit]

In the 1956 NBA draft, Boston Celtics coach Red Auerbach had set his sights on Russell, thinking his defensive toughness and rebounding prowess were the missing pieces the Celtics needed.[1] In retrospect, Auerbach's thoughts were unorthodox. In that period, centers and forwards were defined by their offensive output, and their ability to play defense was secondary.[32]However, Boston's chances of getting Russell seemed slim. Because the Celtics had finished second in the previous season and the worst teams had the highest draft picks, the Celtics had slipped too low in the draft order to pick Russell. In addition, Auerbach had already used his territorial pick to acquire talented forward Tom Heinsohn. But Auerbach knew that the Rochester Royals, who owned the first draft pick, already had a skilled rebounder in Maurice Stokes, were looking for an outside shooting guard and were unwilling to pay Russell the $25,000 signing bonus he requested. Red Auerbach offered the Ice Capades if they didn’t draft Russell number one. Rochester got their ice show.[33] The St. Louis Hawks, who owned the second pick, drafted Russell, but were vying for Celtics center Ed Macauley, a six-time All-Star who had roots in St. Louis. Auerbach agreed to trade Macauley, who had previously asked to be traded to St. Louis in order to be with his sick son, if the Hawks gave up Russell. The owner of St Louis called Auerbach later and demanded more in the trade. Not only did he want Macauley, who was the Celtics premier player at the time, he wanted Cliff Hagan, who had been serving in the military for three years and had not yet played for the Celtics. After much debate, Auerbach agreed to give up Hagan, and the Hawks made the trade.[34]

During that same draft, Boston also drafted guard K. C. Jones, Russell's former USF teammate. Thus, in one night, the Celtics managed to draft three future Hall of Famers: Russell, Jones and Heinsohn.[1] The Russell draft-day trade was later called one of the most important trades in the history of North American sports.[33]

No comments:

Post a Comment