The movie opens in New Mexico.........my "uncle" Steve Maloney.......married to my mother's youngest sister........the youngest of 5.........Diane..............both are into softball.........Red Dogs................in Silver Spring, Maryland.....

Crystal skull

The crystal skulls are human skull hardstone carvings made of clear or milky white quartz (also called "rock crystal"), claimed to be pre-Columbian Mesoamerican artifacts by their alleged finders; however, these claims have been refuted for all of the specimens made available for scientific studies.

The results of these studies demonstrated that those examined were manufactured in the mid-19th century or later, almost certainly in Europe during a time when interest in ancient culture was abundant.[1][2] The skulls were crafted in the 19th century in Germany, quite likely at workshops in the town of Idar-Oberstein, which was renowned for crafting objects made from imported Brazilian quartz in the late 19th century.[3] Despite some claims presented in an assortment of popularizing literature, legends of crystal skulls with mystical powers do not figure in genuine Mesoamerican or other Native American mythologies and spiritual accounts.[4]

The skulls are often claimed to exhibit paranormal phenomena by some members of the New Age movement, and have often been portrayed as such in fiction. Crystal skulls have been a popular subject appearing in numerous sci-fi television series, novels, films, and video games.

Contents

Collections[edit]

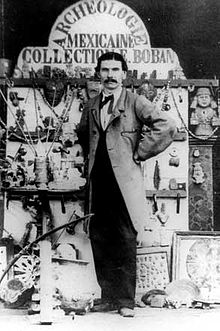

Trade in fake pre-Columbian artifacts developed during the late 19th century to the extent that in 1886, Smithsonian archaeologist William Henry Holmes wrote an article called "The Trade in Spurious Mexican Antiquities" for Science.[5] Although museums had acquired skulls earlier, it was Eugène Boban, an antiquities dealer who opened his shop in Paris in 1870, who is most associated with 19th-century museum collections of crystal skulls. Most of Boban's collection, including three crystal skulls, was sold to the ethnographer Alphonse Pinart, who donated the collection to the Trocadéro Museum, which later became the Musée de l'Homme.

Research[edit]

Many crystal skulls are claimed to be pre-Columbian, usually attributed to the Aztec or Maya civilizations. Mesoamerican art has numerous representations of skulls, but none of the skulls in museum collections come from documented excavations.[6] Research carried out on several crystal skulls at the British Museum in 1967, 1996 and 2004 shows that the indented lines marking the teeth (for these skulls had no separate jawbone, unlike the Mitchell-Hedges skull) were carved using jeweler's equipment (rotary tools) developed in the 19th century, making a supposed pre-Columbian origin problematic.[7]

The type of crystal was determined by examination of chlorite inclusions.[8] It is only found in Madagascar and Brazil, and thus unobtainable or unknown within pre-Columbian Mesoamerica. The study concluded that the skulls were crafted in the 19th century in Germany, quite likely at workshops in the town of Idar-Oberstein, which was renowned for crafting objects made from imported Brazilian quartz in the late 19th century.[3]

It has been established that the crystal skulls in the British Museum and Paris's Musée de l'Homme[9] were originally sold by the French antiquities dealer Eugène Boban, who was operating in Mexico City between 1860 and 1880.[10] The British Museum crystal skull transited through New York's Tiffany & Co., while the Musée de l'Homme's crystal skull was donated by Alphonse Pinart, an ethnographer who had bought it from Boban.

In 1992 the Smithsonian Institution investigated a crystal skull provided by an anonymous source; the source claimed to have purchased it in Mexico City in 1960, and that it was of Aztec origin. The investigation concluded that this skull also was made recently. According to the Smithsonian, Boban acquired his crystal skulls from sources in Germany, aligning with conclusions made by the British Museum.[11]

The Journal of Archaeological Science published a detailed study by the British Museum and the Smithsonian in May 2008.[12] Using electron microscopy and X-ray crystallography, a team of British and American researchers found that the British Museum skull was worked with a harsh abrasive substance such as corundum or diamond, and shaped using a rotary disc tool made from some suitable metal. The Smithsonian specimen had been worked with a different abrasive, namely the silicon-carbon compound carborundum (Silicon carbide) which is a synthetic substance manufactured using modern industrial techniques.[13] Since the synthesis of carborundum dates only to the 1890s and its wider availability to the 20th century, the researchers concluded "[t]he suggestion is that it was made in the 1950s or later".[14]

Other artifacts of controversial origin[edit]

None of the skulls in museums come from documented excavations. A parallel example is provided by obsidian mirrors, ritual objects widely depicted in Aztec art. Although a few surviving obsidian mirrors come from archaeological excavations,[15] none of the Aztec-style obsidian mirrors are so documented. Yet most authorities on Aztec material culture consider the Aztec-style obsidian mirrors as authentic pre-Columbian objects.[16] Archaeologist Michael E. Smith reports a non peer-reviewed find of a small crystal skull at an Aztec site in the Valley of Mexico.[17] Crystal skulls have been described as "A fascinating example of artifacts that have made their way into museums with no scientific evidence to prove their rumored pre-Columbian origins."[18]

A similar case is the "Olmec-style" face mask in jade; hardstone carvings of a face in a mask form. Curators and scholars refer to these as "Olmec-style", as to date no example has been recovered in an archaeologically controlled Olmec context, although they appear Olmec in style. However they have been recovered from sites of other cultures, including one deliberately deposited in the ceremonial precinct of Tenochtitlan (Mexico City), which would presumably have been about 2,000 years old when the Aztecs buried it, suggesting these were as valued and collected as Roman antiquities were in Europe.[19]

Individual skulls[edit]

Mitchell-Hedges skull[edit]

Perhaps the most famous and enigmatic skull was allegedly discovered in 1924 by Anna Mitchell-Hedges, adopted daughter of British adventurer and popular author F.A. Mitchell-Hedges. It is the subject of a video documentary made in 1990, Crystal Skull of Lubaantun.[20] It was examined and described by Smithsonian researchers as "very nearly a replica of the British Museum skull—almost exactly the same shape, but with more detailed modeling of the eyes and the teeth."[21] Mitchell-Hedges claimed that she found the skull buried under a collapsed altar inside a temple in Lubaantun, in British Honduras, now Belize.[22] As far as can be ascertained, F.A. Mitchell-Hedges himself made no mention of the alleged discovery in any of his writings on Lubaantun. Others present at the time of the excavation recorded neither the skull's discovery nor Anna's presence at the dig.[23] Recent evidence has come to light showing that F.A. Mitchell-Hedges purchased the skull at a Sotheby's auction in London on October 15, 1943, from London art dealer Sydney Burney.[24] In December 1943, F.A. Michell-Hedges disclosed his purchase of the skull in a letter to his brother, stating plainly that he acquired it from Burney.[24][25]

The skull is made from a block of clear quartz about the size of a small human cranium, measuring some 5 inches (13 cm) high, 7 inches (18 cm) long and 5 inches (13 cm) wide. The lower jaw is detached. In the early 1970s it came under the temporary care of freelance art restorer Frank Dorland, who claimed upon inspecting it that it had been "carved" with total disregard to the natural crystal axis, and without the use of metal tools. Dorland reported being unable to find any tell-tale scratch marks, except for traces of mechanical grinding on the teeth, and he speculated that it was first chiseled into rough form, probably using diamonds, and the finer shaping, grinding and polishing was achieved through the use of sand over a period of 150 to 300 years. He said it could be up to 12,000 years old. Although various claims have been made over the years regarding the skull's physical properties, such as an allegedly constant temperature of 70 °F (21 °C), Dorland reported that there was no difference in properties between it and other natural quartz crystals.[26]

While in Dorland's care the skull came to the attention of writer Richard Garvin, at the time working at an advertising agency where he supervised Hewlett-Packard's advertising account. Garvin made arrangements for the skull to be examined at Hewlett-Packard's crystal laboratories in Santa Clara, California, where it was subjected to several tests. The labs determined only that it was not a composite as Dorland had supposed, but that it was fashioned from a single crystal of quartz.[27] The laboratory test also established that the lower jaw had been fashioned from the same left-handed growing crystal as the rest of the skull.[28] No investigation was made by Hewlett-Packard as to its method of manufacture or dating.[29]

As well as the traces of mechanical grinding on the teeth noted by Dorland,[30] Mayanist archaeologist Norman Hammond reported that the holes (presumed to be intended for support pegs) showed signs of being made by drilling with metal.[31] Anna Mitchell-Hedges refused subsequent requests to submit the skull for further scientific testing.[32]

The earliest published reference to the skull is the July 1936 issue of the British anthropological journal Man, where it is described as being in the possession of Sydney Burney, a London art dealer who is said to have owned it since 1933.[33] No mention was made of Mitchell-Hedges.

F. A. Mitchell-Hedges mentioned the skull only briefly in the first edition of his autobiography, Danger My Ally (1954), without specifying where or by whom it was found.[34] He merely claimed that "it is at least 3,600 years old and according to legend it was used by the High Priest of the Maya when he was performing esoteric rites. It is said that when he willed death with the help of the skull, death invariably followed".[35] All subsequent editions of Danger My Ally omitted mention of the skull entirely.[32]

In a 1970 letter Anna also stated that she was "told by the few remaining Maya that the skull was used by the high priest to will death."[36] For this reason, the artifact is sometimes referred to as "The Skull of Doom". Anna Mitchell-Hedges toured with the skull from 1967 exhibiting it on a pay-per-view basis.[37] Somewhere between 1988 and 1990 she toured with the skull. She continued to grant interviews about the artifact until her death.

In her last eight years, Anna Mitchell-Hedges lived in Chesterton, Indiana, with Bill Homann, whom she married in 2002. She died on April 11, 2007. Since that time the Mitchell-Hedges Skull has been owned by Homann. He continues to believe in its mystical properties.[38]

In November 2007, Homann took the skull to the office of anthropologist Jane MacLaren Walsh, in the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History for examination.[39] Walsh carried out a detailed examination of the skull using ultraviolet light, a high-powered light microscope, and computerized tomography. Homann took the skull to the museum again in 2008 so it could be filmed for a Smithsonian Networks documentary, Legend of the Crystal Skull, and on this occasion, Walsh was able to take two sets of silicone molds of surface tool marks for scanning electron microscope (SEM) analysis. The SEM micrographs revealed evidence that the crystal had been worked with a high speed, hard metal rotary tool coated with a hard abrasive, such as diamond. Walsh's extensive research on artifacts from Mexico and Central America showed that pre-contact artisans carved stone by abrading the surface with stone or wooden tools, and in later pre-Columbian times, copper tools, in combination with a variety of abrasive sands or pulverized stone. These examinations led Walsh to the conclusion that the skull was probably carved in the 1930s, and was most likely based on the British Museum skull which had been exhibited fairly continuously from 1898.[39]

In the National Geographic Channel documentary, "The Truth Behind the Crystal Skulls", forensic artist Gloria Nusse performed a forensic facial reconstruction over a replica of the skull. According to Nusse, the resulting face had female and European characteristics. As it was hypothesized that the Crystal Skull was a replica of an actual human skull, the conclusion was that it could not have been created by ancient Americans.[40]

British Museum skull[edit]

The crystal skull of the British Museum first appeared in 1881, in the shop of the Paris antiquarian, Eugène Boban. Its origin was not stated in his catalogue of the time. He is said to have tried to sell it to Mexico's national museum as an Aztec artifact, but was unsuccessful. Boban later moved his business to New York City, where the skull was sold to George H. Sisson. It was exhibited at the meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in New York City in 1887 by George F. Kunz.[41] It was sold at auction, and bought by Tiffany and Co., who later sold it at cost to the British Museum in 1897.[42] This skull is very similar to the Mitchell-Hedges skull, although it is less detailed and does not have a movable lower jaw.[43]

The British Museum catalogues the skull's provenance as "probably European, 19th century AD"[44] and describes it as "not an authentic pre-Columbian artefact".[45] It has been established that this skull was made with modern tools, and that it is not authentic.[46]

Paris skull[edit]

The largest of the three skulls sold by Eugène Boban to Alphonse Pinart (sometimes called the Paris Skull), about 10 cm (4 in) high, has a hole drilled vertically through its center.[47] It is part of a collection held at the Musée du Quai Branly, and was subjected to scientific tests carried out in 2007–08 by France's national Centre de recherche et de restauration des musées de France (Centre for Research and Restoration of the Museums in France, or C2RMF). After a series of analyses carried out over three months, C2RMF engineers concluded that it was "certainly not pre-Columbian, it shows traces of polishing and abrasion by modern tools."[48][full citation needed] Particle accelerator tests also revealed occluded traces of water that were dated to the 19th century, and the Quai Branly released a statement that the tests "seem to indicate that it was made late in the 19th century."[49][full citation needed]

In 2009 the C2RMF researchers published results of further investigations to establish when the Paris skull had been carved. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis indicated the use of lapidary machine tools in its carving. The results of a new dating technique known as quartz hydration dating (QHD) demonstrated that the Paris skull had been carved later than a reference quartz specimen artifact, known to have been cut in 1740. The researchers conclude that the SEM and QHD results combined with the skull's known provenance indicate it was carved in the 18th or 19th century.[50]

Smithsonian Skull[edit]

The "Smithsonian Skull", Catalogue No. A562841-0 in the collections of the Department of Anthropology, National Museum of Natural History, was mailed to the Smithsonian Institution anonymously in 1992, and was claimed to be an Aztec object by its donor and was purportedly from the collection of Porfirio Diaz. It is the largest of the skulls, weighing 31 pounds (14 kg) and is 15 inches (38 cm) high. It was carved using carborundum, a modern abrasive. It has been displayed as a modern fake at the National Museum of Natural History.[51]

Comments

Post a Comment