Ok.....my memory was not perfect...............the photo was taken from behind.............he didn't ask the Marines to pose.......he caught them doing what they doing ......in the middle of a battle......so i guess it would make sense to make the beginning of the Memorial from behind to match the photo......but the battle was more than a photo........u usually would want to start it with the Marines facing you...............................

The people who died in battle so they could capture Iwo Jima are more important than a photograph...........i would have the front of the Memorial be the front side of the Marines...(the argument could go either way.....but the men and women who died outweigh, greatly, a photo).....the quote by Admiral Nimitz is where the Marine's backs are........and the Rev. War......1776 being the 1st battle that the Marines were in is on that side............the back side of the Marines.....so i think that that is the front of the Memorial..........b/c you would start a Memorial.......at the beginning ......the famous quote............"Uncommon Valor was a Common Virtue"..........and the 1st war/battle that the Marine participated in.........would logically be the front............They started the US Marine Corps in Tunn Tavern in Philadelphia, PA........in 1775...................the Revolutionary War is the 1st fighting that the Marine Corps saw..........the engraving of the Revolutionary War and Admiral Nimitz quote are on the same side.............which makes me think that that is the front of the Memorial....which is where the Marines backs are facing you.....which matches J. Rosenthal's photo........

Tags:

World War II

The people who died in battle so they could capture Iwo Jima are more important than a photograph...........i would have the front of the Memorial be the front side of the Marines...(the argument could go either way.....but the men and women who died outweigh, greatly, a photo).....the quote by Admiral Nimitz is where the Marine's backs are........and the Rev. War......1776 being the 1st battle that the Marines were in is on that side............the back side of the Marines.....so i think that that is the front of the Memorial..........b/c you would start a Memorial.......at the beginning ......the famous quote............"Uncommon Valor was a Common Virtue"..........and the 1st war/battle that the Marine participated in.........would logically be the front............They started the US Marine Corps in Tunn Tavern in Philadelphia, PA........in 1775...................the Revolutionary War is the 1st fighting that the Marine Corps saw..........the engraving of the Revolutionary War and Admiral Nimitz quote are on the same side.............which makes me think that that is the front of the Memorial....which is where the Marines backs are facing you.....which matches J. Rosenthal's photo........

Read

Rosenthal’s own story about his picture of six U.S. Marines raising the

American flag on Mount Suribachi — perhaps the best-known Pulitzer

Prize-winning photograph.

Perhaps no Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph is better known than Joe Rosenthal’s

picture of six U.S. Marines raising the American flag on Mount

Suribachi on Iwo Jima. It was taken on Friday, Feb. 23, 1945, five days

after the Marines landed on the island. The Associated Press,

Rosenthal’s employer, transmitted the picture to member newspapers 17½

hours later, and it made the front pages of many Sunday papers.

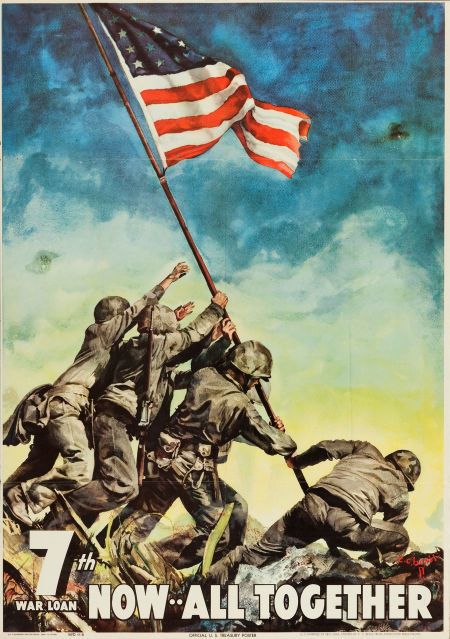

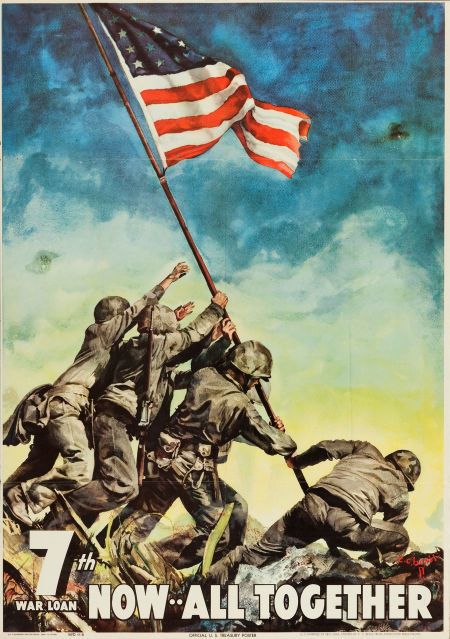

The war-bond poster inspired by Rosenthal's prize-winning photo

The

photo was the centerpiece of a war-bond poster that helped raise $26

billion in 1945. On July 11, before the war had ended, it appeared on a

United States postage stamp. Nine years later it became the model for

the Marine Corps War Memorial in Arlington, Va.

Normally,

the Pulitzer Prize Board considers journalism published in the previous

calendar year for the prizes. It made an exception for Rosenthal’s

picture, awarding it the 1945 prize for Photography a little over two

months after it was taken.

F.A. Resch, The AP’s

executive newsphoto editor, submitted it, supplemented by others taken

by Rosenthal on Iwo Jima, on March 29, 1945. The Photography jury was

just finishing its work and apparently did not consider it.

“We

felt the material was so outstanding that it merited consideration

accordingly,” Fesch wrote to a Pulitzer Advisory Board member.

“The

endless citations which have been made in connection with the

flag-raising picture — in Congress, as the basis for the Seventh War

Loan drive, as the basis for numerous statue and memorial suggestions —

are unprecedented in the history of news pictures.”

The Marine Corps War Memorial in Arlington, Va.

Fesch

pointed out that The AP had transmitted to its members half the 60

pictures Rosenthal made on Iwo Jima. “To the best of my knowledge no

newsphotographer on any assignment before or during this war has

achieved such results either in terms of so many newsworthy pictures

taken under dangerous conditions, or in terms of consistently high

technical quality of the product.”

The Pulitzer Advisory Board acknowledged receipt of the photos on April 18 and assured Fesch they would receive consideration.

A short time later, it was announced that the Rosenthal photo had won the prize.

A

misunderstanding later led to repeated allegations that the photo had

been staged. Sgt. Bill Genaust, who had been with Rosenthal at the time

of the flag-raising and made a film of it, was later killed in action.

His film proved that Rosenthal had not staged the picture.

Here

is Rosenthal’s own story about the picture, which the AP put out on

March 7, 1945, less than two weeks after the flag-raising.

‘I hope this was worth the effort’

“See

that spot of red on the mountainside?” the bos’n shouted above the

noise of our landing craft nearing the shore at the base of Suribachi

Yama.

“A group of Marines is climbing up to plant our flag up there. I heard it from the radioman.”

He was plenty excited — and so was I.

The

fall of this 560-foot fortress in four days of gallant marine fighting

was a great thing. A good story and we should have good pictures.

So

in I went, back to more of that slogging thru the deep volcanic ash,

warily sidestepping the numerous Japanese mines. On past the culverts

where the Japanese dead lay among the wreckage of their own gun

positions and up the steep, winding, always sandy trail.

Marine Pvt. Bob Campbell, a San Francisco buddy of mine, and Sgt. Bill Janausk of Tacoma, Wash., were with me and carried firearms for protection (which is disallowed to correspondents).

Marine Pvt. Bob Campbell, a San Francisco buddy of mine, and Sgt. Bill Janausk of Tacoma, Wash., were with me and carried firearms for protection (which is disallowed to correspondents).

There was an

occasional sharp crack of rifle fire close by and the mountainside had a

porcupine appearance of bristling all over, what with machine and

anti-aircraft guns peering from the dugouts, foxholes and caves. There

were few signs of life from these enemy spots, however. Our men were

systematically blowing out these places and we had to be on our toes to

keep clear of our own demolition squads.

As the

trail became steeper, our panting progress slowed to a few yards at a

time. I began to wonder and hope that this was worth the effort, when

suddenly over the brow of the topmost ridge we could spy men working

with the flagpole they had so laboriously brought up about quarters of

an hour ahead of us.

I came up and stood by a few minutes until they were ready to swing the flagpole into position.

I

crowded back on the inner edge of the volcano’s rim, back as far as I

could, in order to include all I could into the scene within the angle

covered by my camera lens.

I rolled up a couple

of large stones and a Japanese sandbag to raise my short height clear of

an intervening obstruction. I followed up this shot with another of a

group of cheering Marines and then I tried to find the four men I heard

were the actual instigators of the grand adventure. But they had

scattered to their units and I finally gave it up and descended the

mountain to get the pictures out and on their way to possible

publication.

The way down was quite a bit easier,

the path becoming well worn, and men were carrying ammunition,

supplies, food and rations necessary for complete occupation of this

stronghold.

The Marine history will record Iwo Jima as high as any in their many gallant actions in the Pacific.

I have two very vivid memories: The fury of their D-day assault and the thrill of that lofty flag-raising episode.

It is hard now in the quiet atmosphere of this advance base to find words for it. The Marines at Iwo Jima were magnificent.

Comments

Post a Comment